Teenage Dreams, Financial Independence and Abercrombie & Fitch

by Heather Sundell

Before there was Instagram or Pinterest, there was one brick and mortar store that held all aspirational teenage dreams: Abercrombie & Fitch.

I was introduced to Abercrombie in 2001, during the second semester of my sophomore year. My new best friend Sarah had just moved from Colorado to our sleepy California beach town in Orange County. Having also moved just a year and a half prior, I felt a kindred connection with another outsider. We bonded instantly and, like other 15-year-old best friends, we spent all our time at each other’s houses, and in each other’s closets.

In mine, Sarah discovered board shorts, graphic tees, and puka shells in native Southern California surf brands like Roxy, Volcom and Billabong. In hers, I found a foreign wardrobe I’d never seen before: polo shirts, thick sweatshirts with lettering sewn on the front, billowy peasant tops, sporty sweat-shorts, and jeans with the perfect flare. It was clothing designed for preppy people who live in places with seasonal weather — the brand’s original intention — and something I had never had a need for in sunny California. It was all my east coast “Dawson’s Creek” dreams imagined into a fall line.

I had to have it. I had to have it all.

Abercrombie & Fitch. I loved saying it. The name alone sounded cool and, you have to remember, this was before every store and restaurant became ampersand happy.

LFO sang about loving girls who wore Abercrombie & Fitch because it was the epitome of their perfect girl. She was everything on the WB teen drama lineup I wanted to be: smart, fun, athletic, reserved, flirty and, of course, wealthy. You had to be to afford a closet full of A&F, which is something I quickly realized after I dragged my mother to the nearest location at the South Coast Plaza in Costa Mesa for the first time.

The minute I hit the entrance, the distinct intoxicating fragrance — that had to be made entirely of pheromones — engulfed me like my first hit of crystal meth (which I have never done, but I’ve watched “Breaking Bad” so I have a general idea). This was a scent, and a feeling I would constantly crave.

My mom took one look at the price tags and scoffed, “Why would you pay this much for a sweatshirt with a brand name all over it?” My heart sank, but I wasn’t surprised. I had grown up in private schools in Los Angeles, where most of my classmates came from very wealthy industry families. My parents were doing well, but not enough to avoid the ongoing childhood conversation explaining why my friends always had nicer things than me.

So, I did the only thing I could. I got a job.

Just because my parents weren’t going to keep me fully outfitted in moose embroidered clothing didn’t mean I wasn’t going to show up at school looking fly as hell in my new denim skirt.

Being 15 years old, I was legally required to get a work permit from the city until I turned 16. I wanted my white hoodie with the light blue piping on it so badly that I went out of the way to obtain that permit and get my very first job on the end of the Seal Beach pier at Ruby’s, a gimmicky 40’s diner.

With my own money I was able to adequately keep myself in overpriced, preppy and oh-so-smelly clothes. In fact, I kept myself so busy between school, work, homework and extracurricular activities that I didn’t have much time to make it all the way to the store. And, even if I could, I didn’t have my driver’s license yet.

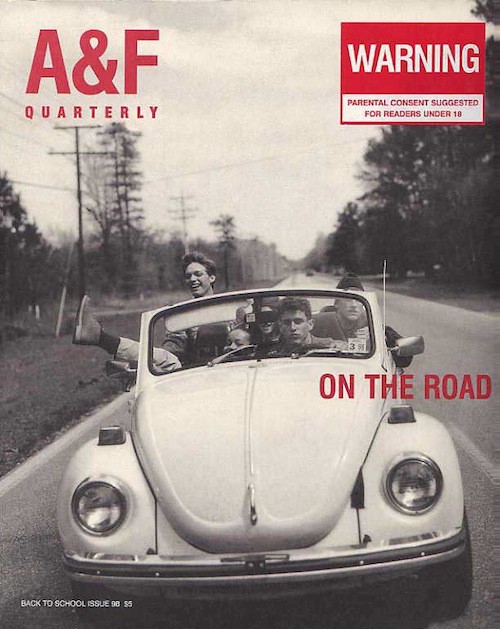

Remember the catalogs? I loved getting them the mail. They were heavy cardstock, reeked of the signature cologne, and featured the hottest all-American models in the world, half clothed on horseback, or sopping wet on the beach. How did they get those henley tees to fit so tight? It was my porn, both as a budding sexual adult and consumer.

The problem with the catalogs was that they came out quarterly, and that wasn’t enough to keep up with my habit. This is when I discovered online shopping for the first time, and it changed my life. Abercrombie had a whole website where I could look at, covet, and order all of their clothes. I could stay up late at night debating if I should get the blue or yellow workout shorts, letting them both hover in my virtual shopping cart until one of them was delivered right to my door. This was the genesis of a long-standing habit of overworking myself to feed my borderline addiction to online shopping that is still with me today.

By the time I got my license and was given a car to use, I was making regular trips out to the mall to burn my hard-earned hostess money at Abercrombie & Fitch. For every birthday and Hanukkah, I listed — in extreme detail — everything I wanted in the store. I was obsessed.

I even got myself hired there for a few months the summer before college started, albeit to work the night shifts like a retail troll. I didn’t care, honestly. I was just there for the discount so I could stock up on cool new clothes for my freshman year at USC.

***

A few weeks ago, my best friend Marissa and I went to an Abercrombie & Fitch. She had received a gift card a couple years ago and, never having a reason to use it in her late twenties, finally blew it on a pair of overalls, because that’s the trend and we’re 30. It’s still somewhat important to do what the kids are doing. It’s also important to remember that clothing designed for teens might not fit your 30-year-old body quite right, which is how she and I found ourselves at the store so she could return her order.

This particular store is located just 10 minutes from my house, and I’d never been before, something my high school self could never possibly understand. Despite growing up on the opposite side of the country, Marissa had a similar relationship to Abercrombie as a teenager: spiritual.

As we approached the store, the familiar scent washed over us, our bodies warmed and tingled. It was not unlike the feeling you get when you come home after a long time away. My muscle memory triggered something latent inside me, giving me a legitimate out of body experience.

I flew around the store touching the tank tops, denim shorts and sweats. I picked up sweaters, gave hoodies the once over, and stopped to inspect a few dresses. I felt out of control. I felt giddy. This was the first time I had been in an Abercrombie & Fitch as an adult, with complete autonomy over everything in my life.

I ended up grabbing an army green romper and taking it to the dressing room, which I had to wait to use for several minutes because I realized, with much impatience, that there were only teenagers running the store.

I hurriedly sidled out of my clothes and into the Abercrombie. I looked in the mirror. It was OK, not great. I decided to keep looking around, until I found myself in the sale section. I felt dejected and conflicted that I innately wanted to purchase something but couldn’t find anything I actually liked and wanted to wear. I also felt so confused by the price tags. Why was everything … so cheap? I didn’t get it because $40 for a sweater didn’t feel completely unreasonable to me.

I wondered if the company, facing the recent horrific public backlash to their former superficial, asshole CEO, was forced to lower their prices. But, I realized, it wasn’t Abercrombie that had changed; it was me.

That comforting feeling of coming home suddenly felt disappointing, like visiting an old childhood house as an adult, only to find it small, dingy, and not nearly as magical. I saw the store for what it was: a ridiculous brand that stands for nothing good.

Since my teenage obsession and idolization of the models, brand, and carefree coastal lifestyle of Abercrombie, the company has been publically — and rightfully — put through the ringer (including recently losing a discrimination case that had reached the Supreme Court). Appointed in 1992, former Abercrombie CEO Mike Jefferies was both responsible for creating the exclusive aspirational club of my teenage dreams, as well as its demise well after I had discarded the brand as “not my style.” Last year, after 11 consecutive quarters of declining sales and a slew of cringe-worthy discrimination accusations and charges, Jeffries stepped down. It’s hard to come back after you’ve said that your product is made specifically for the “cool kids — the attractive all-American kid with a great attitude and a lot of friends.” Exclusivity is so not cool.

The age of Abercrombie had long been over.

Having spent several years away from Abercrombie, I recognized it hadn’t experienced a decline. It was always this crappy. Their shitty clothes weren’t any cheaper than they were almost two decades ago, and the values they stood for were no less grimy. In retrospect, when I worked there, I probably had to work the night shift because I didn’t physically make the cut to be shown off on the floor during the day.

It’s just that now, in the broad light of adulthood, I can finally see them for what they really are. My perspective on what things cost, both monetarily and sociologically, has altered dramatically.

I now understand that Abercrombie was never my real addiction — it was the financial freedom it forced me to find, and for that I am eternally grateful. To this day, I know that I can have anything I want in the world if I work for it, and I am confident I can get it all by myself.

Heather Sundell lives in Los Angeles. This is her blog.

Photo: Alan Light

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments