‘The Road To Character Is Often Paved With Family Money’

Sunday’s editorial by Lee Siegel, “Why I Defaulted On My Student Loans,” is definitely the money-related must read from the weekend. It is a fiery, unapologetic indictment of our capitalist system, which all but mandates higher education for those trying to get ahead and yet puts it increasingly out of reach:

Some people will maintain that a bankrupt father, an impecunious background and impractical dreams are just the luck of the draw. Someone with character would have paid off those loans and let the chips fall where they may. But I have found, after some decades on this earth, that the road to character is often paved with family money and family connections, not to mention 14 percent effective tax rates on seven-figure incomes.

Moneyed stumbles never seem to have much consequence. Tax fraud, insider trading, almost criminal nepotism — these won’t knock you off the straight and narrow. But if you’re poor and miss a child-support payment, or if you’re middle class and default on your student loans, then God help you.

Forty years after I took out my first student loan, and 30 years after getting my last, the Department of Education is still pursuing the unpaid balance. My mother, who co-signed some of the loans, is dead. The banks that made them have all gone under. I doubt that anyone can even find the promissory notes.

To my mind, you have to admire this guy, even if you don’t agree with him. He is taking a bold stance and using it to make a broader, and vital, point about the economic injustices we’re willing to put up with in this country. Also his anger. There’s something so compelling about it. Maybe because I’ve started watching “The Americans”?

I mean, you could read the entire, peppery piece about why Siegel has opted out of a system that he calls “legal but not moral,” or I guess you could watch this Al Pacino clip and get the same basic idea.

When you think about it, it’s amazing that we don’t let 17-year-old children drink or vote — and, in fact, we still refer to them as “children” — yet we are okay letting them sign papers they cannot be expected to fully understand, the implications of which will, in many ways, determine their financial futures. Can we then really blame them when they come to their senses and opt out?

There are lots of rueful quotes on The Empowered Dollar about this:

When I was a senior in high school applying to schools (disgustingly expensive, private colleges, mind you), the price tag didn’t faze me. Forty-thousand dollars a year for four year didn’t seem like real money to me. I wasn’t responsible for thinking about how I was going to pay it back right now. It also felt like I didn’t have a choice. I accepted the fact that college was an unaffordable next step in my life, and the only way to advance my academic career was with tons of debt.

Let’s not forget there is often a racial component to this system, too. Half of black college students graduate with more than $25,000 in student loan debt.

For black students this cost is often greater than for their white classmates. This burden often follows them for decades after school, reinforcing income and racial inequalities that are so prominent in the US.

A Gallup poll released in September found that in the last 14 years about half of black college students graduated with student debt over $25,000 — whereas only 35% of white students did. During that same time, the number of black Americans enrolled in college had increased by 74%. In 2012, the total number of black college students was 2.96 million, up from 1.7 million in 2000. Black students make up 15% of US college students.

Generation [Dragonball] Z seems to have gotten the message from watching the rest of us that debt is a deep pit of despair:

A quarter of the respondents said they don’t think any amount of debt is manageable, and 45 percent said that they could only handle debt payments of $100 a month. Nearly two-thirds said they were concerned about being able to get a job and 60 percent expressed concern about having enough money as adults. Nearly one-third of the teenagers said college costs are “not worth it” and that the “costs will outweigh the benefits.”

What will that mean for their futures, and for our future as a nation? If nothing changes on a large scale in terms of how we assign and handle debt, will college end up, once again, the domain of the privileged few?

Oh, and whether or not you make a point of reading the comments, read this one on Siegel’s piece. It makes its point with heartbreaking clarity.

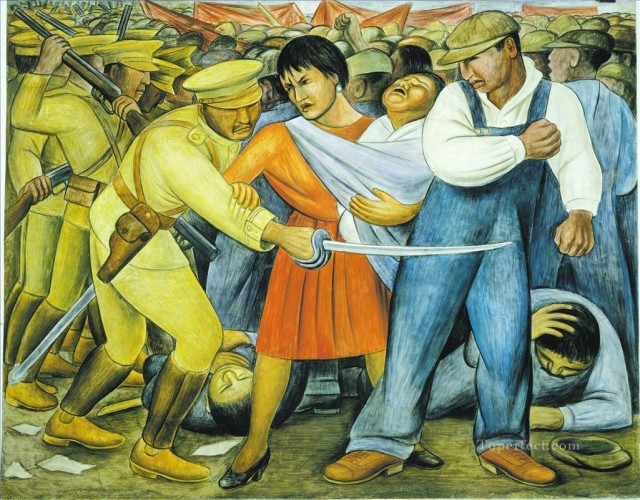

Diego Rivera image via ToPerfect.com

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments