How the Digital Era Has Made Us Better and Worse Tippers

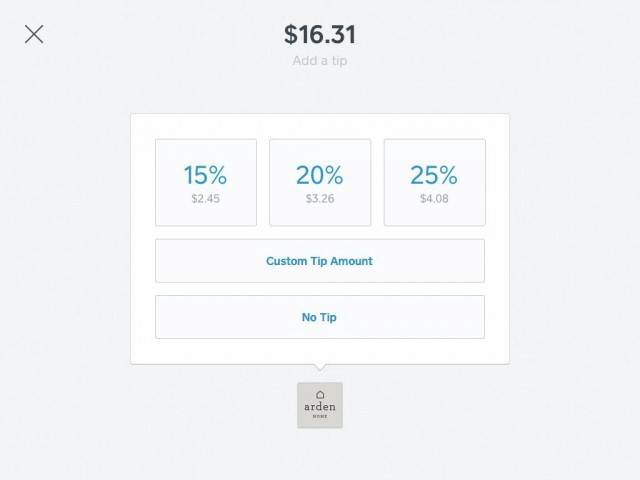

I took a cab to the airport for a work trip recently and when I swiped my credit card to pay, the screen asked me if I wanted to tip 15, 20, or 25 percent. Sure, 25 percent sounds good, I thought.

At a coffee shop the next week, I purchased a $4 cappuccino and two Askinosie chocolate bars at $9 a pop that I had planned to give to friends. When the screen asked for a tip, I selected the 20 percent option without thinking too much about it. If I had paid with cash, I would have tipped one or two dollars to the barista for making me the cappuccino, but with the screen tipping options placed in front of me, I had tipped more than $4. The screens made me tip more than I usually would.

The psychological effect that these digital screens have had on tipping has been covered in places like The New York Times and Bon Appétit, which points out that “anchoring” the tips at higher percentages has helped increase the amount that consumers give:

When the Big Apple’s taxis began adopting credit-card readers, many lifelong New Yorkers were shocked to discover that they’d apparently been undertipping their cabbies for years — at the checkout screen, they were presented with their tip choices, with 20 percent being the smallest option. (A small, easily missed button in the corner allows riders to enter other amounts.) Of course, they hadn’t really been undertipping before, but thanks to the way the screens were laid out, 20 percent became the new norm overnight. It’s a strategy known as anchoring, subtly or not so subtly establishing a new standard by shifting the choices you present. If you want Team Big Tippers to score more touchdowns, you’re going to help them immensely by moving the 50-yard line toward the goal.

If this digital option for tipping has made some of us tip better, then it could be true that it has also made some of tip worse too, right? There’s not much in the research that shows this, but a recent story by Julia Carrie Wong in SF Weekly examining the independent contractors who work for on-demand service companies like Uber, Instacart and Postmates shows that this can be the case.

Wong follows Evelyn, a contract worker for Postmates, an on-demand delivery service where customers can use an app that “enabl[es] anyone to get any product delivered in under one hour.” Evelyn tells Wong she was able to earn as much as $25 an hour doing courier work for Postmates, but contract workers for Postmates reported that once the company updated its app and changed the way users could tip workers, their earnings dropped dramatically:

For couriers, two separate and important issues were involved in this update. Previously, customers had to fill out a checkout screen on the courier’s smartphone — OKing their order and adding a tip if they chose. But with checkout moved to the customer’s phone, the only interaction at the door became the handing off of the delivery items. There was less time for couriers to humanize themselves and less interpersonal pressure on the customer to acknowledge the courier’s work with a tip. The new tip screen also changed the tip options from percentages (5%/10%/15%) to dollar amounts, undermining the chances that a big-ticket order would result in a proportionally large tip…

…under the new system, Daniel’s earnings fell by about a third. “A lot of people will just say, ‘Oh thank you,’ and they’ll take their merchandise, they’ll take their burritos or whatever, and they’ll just turn around and go back in the door,” he says. “There’s no interaction. It seemed more professional when you showed the order to them and they had to sign it. There was kind of a community feeling, having this brief but pivotal exchange. It meant something. Now it’s just like, ‘I’m going to get something dropped off to me, see ya!’”

Wong goes on to report that contract workers for companies like Postmates have no recourse, but a lawyer named Shannon Liss-Riordan has been filing class-action lawsuits against on-demand companies like Uber, Lyft, and Postmates on behalf of workers, arguing that they’re misclassified as contract workers, when these companies are really dependent on their labor as actual employees and are profiting off of them without having to provide any benefits (by doing things like payroll taxes and providing health care).

Uber is currently Liss-Riordan’s biggest target, and it also happens to be a company that instructs drivers to not accept tips, which is one reason I’ve declined to use the service. If a contract worker is providing me with a service, I’d like to be able to tip enough to show my appreciation — and help her pay for the health care, taxes, and other expenses she’s responsible for providing for herself.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments