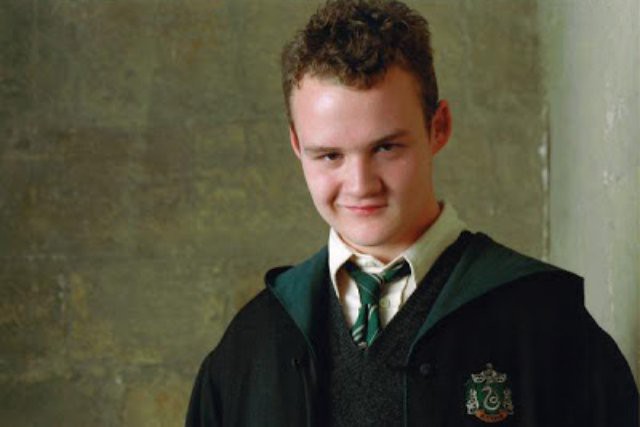

How Wizards Do Money: Gregory Goyle

There were two types of Hogwarts students: the “well-adjusted” ones, who came rushing out of the Second Wizarding War with blood on their hands and smiles on their faces, ready to start their new lives, and the others.

It was a bit arbitrary; some people who had seen loved ones killed in front of them were fine, they smiled and held yearly memorials and said sweet nothings like “she died fighting evil” or, worse, “he died in service of Our School.” These were often the same people who went back to Hogwarts, afterwards. It was Our School, right? Time to finish the semester and graduate!

Goyle’s sentiments were a bit different. He had been pulled out of a room in which he should have died. His best friend had been left behind to die. And the same smug faces that saved his life were now skipping and grinning in the pages of every newspaper he saw. “Ministry Official Hermione Granger Describes Happy And Free as “A True Success.”

Gregory Goyle refused to be “well-adjusted.”

After the war he found himself a bit on the wrong side of everything; he was a former Hogwarts student, which earned him a veneer of sympathy, but he was also associated with the Malfoy family and the Death Eaters, which meant that nobody actually felt sorry for him. He wondered if people wished he had died, trapped in the Room of Requirement with Vincent Crabbe. He saw them all imagining an alternate version of the story in which he did die.

Like many young wizards, when Goyle discovered there was an entire Muggle world hiding just outside of his own, he felt betrayed. Why had nobody told him about this? He thought about the times he had laughed at first-year students who arrived at Hogwarts goggle-eyed at the floating candles and moving staircases. He thought about that the first time he rode the London Underground, because after the Second Wizarding War Goyle became one of the other types of Hogwarts students: the ones that left Hogwarts and the wizarding world forever.

When he stepped out into the streets of London and stood staring at the enormous lights, with images flashing and moving that were bigger than any moving image he’d ever seen in a newspaper, the first thing he wanted to do was hit someone. Or something. Anything. This world had existed the entire time and it was overwhelming and Goyle didn’t know what to do with it. He ended up doing magic, a simple charm that got him a man’s wallet, and he didn’t know what to do with the money inside but he walked around with it, handing it to a woman in exchange for a hamburger and then handing a lot of it to a man in exchange for a hotel room.

And then he sat in his hotel room, quietly, until he found himself punching the mattress, harder and harder, until he could not see for tears.

Goyle would have ended up in prison if he hadn’t been quick with that theft charm. He spent his first month in London nicking wallets as he tried to figure out where he was, and how the money worked, and what he was supposed to do with the rest of his life. He saw a room with a bunch of men punching things that hung from the ceiling, and he went in and started whaling on one of the bags, still in his overcoat and street shoes, until a man in a brightly-colored T-shirt walked him over to a desk and asked him to pay, and Goyle pulled out somebody’s wallet and found it empty, and turned around and walked out, first trying not to cry and then not caring if he did.

He walked by that building with its glass front window three more times, and then he stole one more wallet — it was the last wallet he would ever steal, which was something he didn’t quite believe when he told himself but turned out to be true — and bought the same clothes the men in that building were wearing, and he walked up the next day in his own T-shirt, like he matched, and handed over cash money, like he matched, and began punching one of the bags like it was the place where he had always belonged.

His new friends told him his technique was wrong and helped him improve it. His new friends bought him a round of drinks at a pub, and when they pulled out little shiny rectangles to pay for it, Goyle didn’t say “wait, those things counted as money this entire time?” he just kept his mouth shut and ate more chips. His new friends told him he was probably too old to train to be a boxer, his technique was never going to be strong enough, but they knew this guy who needed a good bouncer, and that was how Goyle got his first job and his own magical money rectangle.

He went to the gym every day. His new friends had girlfriends or boyfriends and one of them had a new baby and one of them had a space in a flat for him since another roommate had just moved out. Goyle kept his mouth shut a lot, because he knew that sometimes he said something that he thought meant “friendship” but actually hurt his friends’ feelings, he could see it in their eyes. He didn’t know how to be a good friend, not yet, but he was learning.

Previously: Stan Shunpike

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments