‘Submissive Students Do Not Make Good Computer Scientists’

by Sorelle Friedler

For years, I’ve been following the “progress” of “no excuses” charters schools from afar and wondering why something about them seemed wrong. This week, the Washington Post did an excellent interview with Professor Joan Goodman of the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education that illuminated the underlying problem: charter schools are teaching students to be submissive.

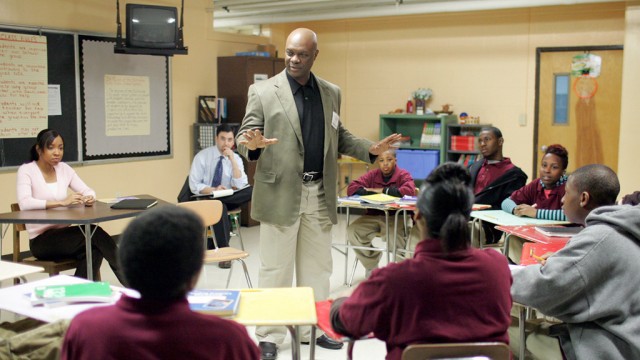

The students are expected to sit still for hours in an often extended school day. Interactions and bodily functions are highly structured; permission is needed to go to the bathroom or sharpen a pencil; students are expected to look at the teacher at all times with their hands folded on their desks. The teacher is to be seen as the authority, not just over the material, but over the students’ own bodies as well. According to the Washington Post, students who do not submit are punished or humiliated: through detentions, by being forced to wear different colored shirts, or by not being allowed to talk to other students.

These schools claim they are preparing students for success, for college. As a college teacher, I want to be clear: this is not what success looks like in my classroom. These are not the habits I want my students to have. I want my students to be creative problem solvers, leaders who think for themselves, critical thinkers willing and able to challenge authority.

Students in my classroom work in groups both inside and outside of class. It’s a noisy, animated environment. They cross the classroom, without asking for permission, to talk to someone about a problem. They volunteer answers, sometimes without raising their hands. If I make a mistake, they correct me. These are the things they should be learning to do in high school, to actively engage with the material and the people around them. The students who struggle in college are almost always the quiet ones. The ones who think that they’re doing what they’re supposed to do by remaining silently in the back of the classroom with their notebook out and their feet planted firmly on the ground; the students who think that as long as they take neat notes and submissively listen, they’ll do well in my class.

That is not what learning looks like in my classroom. This is a myth we need to dispel.

Many claim that “these students” need discipline. I agree that discipline is important. But I worry that these schools teach discipline of the body and not of the mind. I certainly don’t sit silently in one place while doing deep thinking, and I don’t expect students to do so either. In fact, I believe that requiring that would hinder my ability to think productively, as my thought energy would be going towards not moving instead of actually thinking about the problem at hand.

I don’t want students to learn that how they act when they say something is more important than what they say. I believe the best way to teach discipline of the mind is to have students work hard on hard problems. I like to believe that the work is interesting enough to motivate that.

We should also be attentive to our instructions to “these students” that we don’t give to all students. Stereotypically, the students taught by these schools, the ones who supposedly need such strict discipline, are poor students of color, while the students taught by good public and private schools where these methods aren’t used are white and well-off. There is a large body of educational work on the “hidden curriculum” — what we teach our students about society and their role in it by how we teach them. It seems to me that by making these students submit to their teachers’ absolute authority, we are training them to be service workers, not CEOs. Instead of doing what they claim, lifting the students out of poverty by giving them access to higher education, I believe these “no excuses” charter schools are perpetuating the status quo.

I am a computer science professor, a discipline that loves to “disrupt.” Yet many companies and tech CEOs support these schools, monetarily and through public statements of support. These schools are the opposite of disruptive and do not teach students the learning skills we need them to have. There are more tech jobs than qualified graduates each year. And we need well prepared students.

Submissive students do not make good computer scientists. We need problem solvers who think outside the box and move technology forward. We especially need such skills from outside our existing very white community to drive tech forward in a more inclusive, useful way.

As college educators and computer scientists we have allowed these “no excuses” charter schools to use our tacit approval as an endorsement for too long. We need to speak up and say that we expect more. That these schools are not doing a good job preparing students for college or for tech careers. We need to be clear that they do not do this on our behalf.

Sorelle Friedler is an assistant professor of computer science at Haverford College. Previously, she worked as a software engineer for Google, a national partner of KIPP, a “no excuses” charter school.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments