Here’s A Surefire Tax Estimating Process for Freelancers (Rebooted and Updated)

I wrote about my surefire tax estimation system for freelancers for the Billfold in the hopes that a system that has worked for me would help the many Billfold readers who live partly or entirely on freelance income avoid quarterly or annual financial panic when it came to dealing with their taxes. “This system is incredibly useful!” some said. “This system is insanely complex, how can you expect anyone to actually do this,” said many others. “Please help me,” said an unsettling number of emails I’ve received.

I’m actually going to offer you several potential ways you can manage your freelance tax burden. They will get increasingly more complicated as you get deeper into the article — and also increasingly more accurate, in the sense that you will be less and less likely to overpay or underpay your taxes over the course of the year. But any of them will be better than the system that many of you are using, which (as near as I can tell from the emails I get) is to ignore the fact that you need to do tax estimates until you fill out your 1040 in the spring and realize you owe the government thousands and thousands of dollars.

Ready to avoid that? Let’s start! First up: a brief discussion of why you need to do this, why you can do this even though it feels impossible right now, and why the whole problem is so difficult.

I can’t afford to pay my taxes!

This is a thing I often hear people say about paying their quarterly tax estimates. Maybe you’ve said it! My first response is that I don’t know your life. Maybe you are in a situation where you literally aren’t making enough to survive and pay your taxes, and need to make some radical changes (new job, new living situation, bankruptcy, etc.). But I think in many cases, this feeling stems from thinking about your freelance income the wrong way.

Most people with a full-time job who get paid a salary or hourly wage probably know what their annual income is. “I make $50,000 a year!” they say, or “I make $12 an hour!” But when it comes to budgeting, or just having an instinctual knowledge of how much they can safely spend, they use as a baseline their take-home pay. And the trick is: that take-home pay has already had taxes deducted from it. If you make $50,000 a year, and you get paid every other week, and you multiply your paycheck by 26, you discover that you don’t take $50,000 home; you actually take home a bit more than $35,000, according to this handy paycheck calculator (that’s assuming you live in New York City, and don’t have anything taken out for health insurance or 401(k). And you learn to live on that! Because you never had a choice! That $15,000 or so in taxes you paid over the year was never in your hands to being with.

The problem emerges for most people when they shift from salary to freelance. Used to getting (say) a $1,500 paycheck every other week, they get (say) a $1,500 check for writing a magazine article (LOL does this ever happen please let me know if so) and think it’s pretty much the same thing. It very much is not the same thing. That $1,500 check from GQ hasn’t had taxes taken out. Part of that check — probably a much larger part than you’d guess — is not yours. It’s already owed to the government. And in fact, every check you get for your freelance work boosts the amount you owe to the government. The crisis erupts when, four times a year, or maybe just once a year, you figure out how much debt to the government you’ve accumulated and it’s a big number, and you don’t have money to pay that number because you’ve been treating those $1,500 freelance checks like they’re $1,500 paychecks, which they’re not. You need to take this into consideration when setting your rates and asking for money. If you want a $1,500 paycheck, as you’ll see, you’ll need to ask for something around $1,900 in freelance pay.

Yes, you have other bills to pay in addition to your taxes, of course. But let’s be real: the IRS is about the worst creditor you can have, short of the mafia. They are going to get that money out of you, sooner or later.

The key to avoiding this crisis is to segregate the amount you owe in taxes from your spending money as soon as you can, maybe even as soon as you make it. This will give you a much more immediate sense of how much you really make, what sort of lifestyle you can really afford, and what sort of financial changes you need to make to live within your means. Small frequent payments are easier to manage than large infrequent ones, so you won’t encounter terrible sticker shock. All the systems I’m going to outline in this article will look more or less like this:

1. Get paid as a freelancer, via check, PayPal, whatever.

2.Take a portion of that freelance payment and put it somewhere separate from the rest of your money. Maybe it’s a separate named savings account at your bank or with CapitolOne online. Maybe it’s in cash in a coffee can in your sock drawer. I’m going to refer to this as “your special tax account” throughout this article. The point is that you put it there and you never touch it. Forget about it! It’s not yours! You’re just keeping it warm for Uncle Sam!

3. Put the rest in whatever account/wad of cash you use to buy food, housing, drugs, etc.

4. Four times a year, when quarterly taxes come due, send what’s in your special tax account to the IRS. The due dates, addresses where you send the checks, and voucher forms to fill out are all in Form 1040ES.

Obviously the key question here is: Exactly how big should the portion in step two be? I wish this had an answer that was both easy and accurate. Unfortunately for this enterprise (although fortunately is just about every other way), the U.S. has a progressive taxation system, in which you pay a higher percentage of your income in taxes the more you make; combine this with the fact that many freelancers’ income can vary wildly over the course of the year, and this calculation actually becomes devilishly complex. But we’re going to try to make it work. Here are three different ways to approach the problem, in increasing order of complexity.

1. The simplest, quickest, and potentially least accurate method

If you hate math, hate record-keeping, don’t really know how much you make a year and are terrified of actually figuring it out, but still want to avoid the mounting and wholly justified panic that comes from never ever paying your estimated taxes, this is the method I’d recommend.

1. Receive a freelance check/PayPal payment/whatever kind of payment.

2. Put 25% (that’s one-quarter) of the amount of that payment into your special tax account.

3. Put the rest in whatever account/wad of cash you use to buy food, housing, drugs, etc.

4. Four times a year, when quarterly taxes come due, send what’s in your special tax account to the IRS. (Keep track of the amounts you send in; you’ll need them when you do your taxes next year, and you don’t get the equivalent of a W2 from the government telling you how much you paid in estimated taxes.)

And that’s it! Pretty simple, right? So, using our example above of you and your awesome GQ article, you need to stick $375 of that check from them in your special tax account.

(If you want to add a little bit more accuracy here and only a little bit more complication, you might want to keep track of all the money you’ve spent on business expenses since the last time you got a freelance check and then deduct it from your payment. So, if you made that $1,500 from GQ, but that same week bought a $200 voice recorder that you plan to use for interviews, treat that payment like $1,300 for the purposes of estimating your taxes, and put $325 in your special tax account. Just make sure you don’t count any business expenses more than once.)

The problem with this method is not everybody will owe 25% of their income to the IRS, because we don’t have a flat tax system. If you don’t make very much money, you’ll be overpaying, which might pinch (though you will get a nice refund back at tax time next year). If you make more, you’ll be underpaying, and will need to write a check at a tax time and maybe even pay a penalty. But it’s in the right ballpark and will prevent total tax-time disaster.

2. A slightly more nuanced method

This method is pretty much the same as method 1, except that it actually takes into account how much you make in figuring out how much you should set aside. This system works if you have a general sense, to the nearest $10K or so, of how much you’ll make this year. Basically, I’ve plugged a bunch of potential salaries into the tax code and figured out what percentage that salary you’d owe in taxes for each, including both federal income tax and self-employment tax.

1. Receive a freelance check/PayPal payment/whatever kind of payment.

2. Put the percentage of that payment that matches lines up with your total annual income and tax status from the rough-and-ready tax table below into your special tax account. Remember that when I say total annual income, I mean your freelance and salary income combined, if you have any salary income you get from working a regular job — and, if you’re filing jointly with your spouse, you need to include their income in that total too.

3. Put the rest in whatever account/wad of cash you use to buy food, housing, drugs, etc.

4. Four times a year, when quarterly taxes come due, send what’s in your special tax account to the IRS. (Keep track of the amounts you send in; you’ll need them when you do your taxes next year, and you don’t get the equivalent of a W2 from the government telling you how much you paid in estimated taxes.)

ROUGH-AND-READY TAX TABLE

These amounts only go up to $100,000 because if you make that amount of money it’s frankly ridiculous that you’re getting your tax estimation advice from this article. Please, for the love of God, hire an accountant. You can afford it. Anyway!

Filing status: Single or married filing separately

• $10,000: 14%

• $20,000: 18%

• $30,000: 21%

• $40,000: 23%

• $50,000: 24%

• $60,000: 26%

• $70,000: 28%

• $80,000: 29%

• $90,000: 30%

• $100,000: 31%

Filing status: Married filing jointly

• $10,000: 14%

• $20,000: 17%

• $30,000: 18%

• $40,000: 20%

• $50,000: 22%

• $60,000: 23%

• $70,000: 24%

• $80,000: 25%

• $90,000: 25%

• $100,000: 27%

So, again, revisiting your lucky $1,500 GQ payday: If you’re single and expect to make $30,000 in total this year, put 21%, or $315, in your special savings account. If you’re married and will be filing jointly, and you expect that you and your spouse will make $100,000 between the two of you this year, put 27%, or $405, in your special savings account.

(Again, you can add a bit more complication/accuracy by keeping track of your business expenses since your last payday. So, if you made that $1,500 from GQ, but that same week bought a $200 voice recorder that you plan to use for interviews, treat that payment like a $1,300 for the purposes of estimating your taxes. Just make sure you don’t count any business expenses more than once.)

This is honestly a perfectly good and, I would hope, easily managed system for someone who makes money freelancing that’s pretty steady, and knows how much that is. It may in fact be all you need! But it does require that you know more or less how much money you’re going to make over the course of the year. If you’re really unsure what you’re going to make, or if you aresure but turn out to be wrong, you could end up overpaying or underpaying by quite a bit. If you want to keep up with how your income fluctuates over the course of the year, things get a lot more complicated.

3. The full-on Josh Fruhlinger super-accurate and yet kind of insane method

Are you just plain not sure what you’ll make over the course of the coming year? Do you want to accommodate swings in income over the course of the year? Do you want to be sure that the amount you pre-pay in taxes is very close to what you actually owe? Do you like math and record keeping? Well, then hang on for the ride of your life, my friends, because this is how I estimate my taxes, and it’s pretty gnarly/fun (for certain people’s ideas of fun.)

In the previous methods, you set aside a portion of your freelance income every time you receive a payment. In this method, you’ll instead figure out what you need to put into your special tax account on a regular basis over the course of the year. I recommend doing this no less than once a month, to make sure what you owe doesn’t build up to shocking proportions; I do it twice a month.

This method requires you to keep some records of your income over the course of the year. Yes, every time you figure out your taxes, once or twice a month, you’ll figure them out based on the whole year’s income so far. This is how you keep an accurate pace of how much you owe based on your estimated annual salary, even if wild swings in income mean that your estimated annual salary changes over the course of the year. So, every time you figure out your estimated taxes, you’ll need to know:

• How much your freelance profit has been so far this year (i.e., your freelance income minus business expenses)

• How much you’ve already paid in estimated taxes so far this year

• How much in taxable salary or hourly wages you (plus, if you’re married filing jointly, your spouse) has made so far this year, if anything

• How much Federal income tax you (plus, if you’re married filing jointly, your spouse) have had deducted from your paycheck so far this year, if anything

(Since paychecks are generally the same every pay period, you can figure out those second two figures by multiplying the amounts on your paystub by however many pay periods have passed this year. Make sure to use your “Federal taxable income” for this calculation, not your gross pay.)

Step 1: Take the amount of money you’ve made freelancing so far this year and divide it by the number of months that have passed so far this year. (Feel free to use half-months, e.g., on March 15, 2.5 months have passed so far.) Then multiply the result by 12. This is your estimated annual freelance income.

Step 2: Multiply your estimated annual freelance income (the result from Step 1) by 0.1413. This is your estimated self-employment tax for the year.

Step 3: If you (or, if you’re married and filing jointly, your spouse) have any income from non-freelance salary, divide the total earned so far this year by the number of months that have passed so far this year. Then multiply the result by 12. Call this your estimated annual non-freelance income.

Step 4: Take your estimated annual income (the results from Step 1), and subtract half of your self-employment tax (the result from Step 2). Then add your estimated annual non-freelance income (the result from Step 3), if any. Take that total and subtract either 10,300 (if you’re single or married filing separately) or $20,600 (if you’re married filing jointly) from it. This is your estimated taxable income for the year.

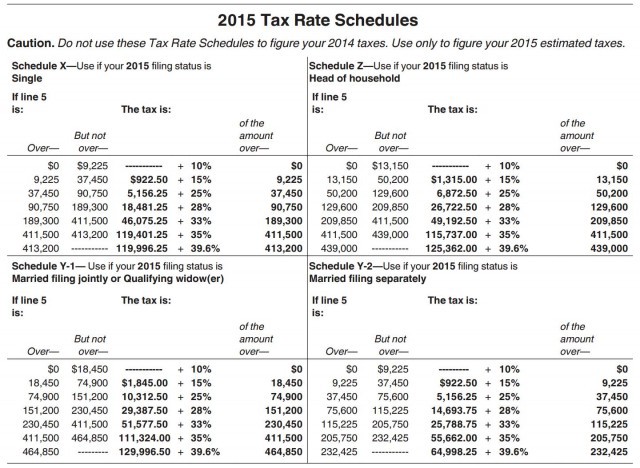

Step 5: Use the chart below to figure out your estimated income tax for the year. This is taken right out of IRS Form 1040ES. When it says “Line 5,” use your estimated taxable income for the year, aka the results of Step 4.

Step 6: Add together your estimated self-employment tax (the results from Step 2) and your estimated income tax (the results from Step 5). This is your total estimated tax for the year. Divide this by 12, then multiply that by the number of months that have actually passed this year. This your estimated tax liability so far this year.

Step 7: Subtract from your estimated tax liability so far this year (the results from Step 6) the amount you’ve already paid in quarterly estimates and the amounts you’ve had deducted from your paycheck so far this year (if any). This is the amount you should have in your special tax account right now.

Step 8: Subtract the amount you actually have in your special account (if any) from the amount you should have in your special account (the results from Step 7). Move the difference from wherever it is you usually keep your money into your special tax account.

Step 9: Repeat this process once or twice a month. Remember, every time you do it, start with the full amount of money you’ve made for the whole year so far, not just the amount since the last time you estimated your taxes.

Step 10: Whenever it’s time to make your quarterly payment, just write Uncle Sam a check for the amount that’s in your special account (obviously you’ll need to move it from your special account to your checking account). The due dates, addresses where you send the checks, and voucher forms to fill out are all in Form 1040ES.

And there you have it: your key to tax peace of mind, in only 10 easy steps! Yes, I’d probably use one of the first two methods if I were you too.

Important epilogue: But what about state taxes?

Ah, yes, you’ve spotted the most glaring omission from this method: state income taxes. Unless you live in one of the nine states colored red or yellow on this map, you should in theory be estimating your state taxes along with your federal taxes during this process. Unfortunately breaking down the math for each of the other 41 states would make this article completely unwieldy.

If you’ve freelanced in previous years, one trick you might want to use is to look at last year’s taxes and see what the ratio of your state tax to federal tax totals were. For instance, if you paid four times more in Federal taxes than state taxes, you’d want to set aside for the state a quarter of what you’d set aside for the Feds. Using our GQ example from the first method above, when you get that $1,500 check from GQ, in addition to that $375 for the Feds, set aside $94 for your state.

In general, state taxes are generally simpler than Federal taxes, if you’d like to make a go at adding that math to the mix yourself. You can find the tax brackets in your state’s equivalent of a 1040ES form, and apply them to your estimated taxable income in step 5 of the more complicated method I describe. They’re also usually substantially lower than Federal taxes; my state prepayments are usually only about a quarter of my Federal prepayments, and I live in Maryland, a relatively high-tax state, so you may be brave enough to put off the payments to once a year. But if you’re really anxious to figure your state taxes but feel at sea with the math, please email me and I’ll try to help. We’re all in this together!

Josh Fruhlinger would like to emphasize very strongly that he is not a professional accountant. He’s just a guy who’s been freelancing for 12 years and has done OK for himself tax-wise. He runs the #1 Mary Worth fan site on the Internet, and also has a Tumblr and a Twitter.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments