The Cost of a Car Accident

by Kate Abbott

It was a Friday morning, one of those sunny days where I felt grateful to be at home with my baby, Henry. He and I had just gotten our flu shots earlier that week, and today we had nothing to do but relax. On this day, it seemed welcoming instead of terrifying to be alone with him. My husband Brad was going that morning to get his own immunization. The cost of our vaccines: free, at our doctor’s office, without even a co-pay.

It was early November, it was warm, and we could go outside; we could do what we wanted to do. I had just gotten Henry dressed into a green onesie with a recycling symbol on the front, with matching little fuzzy leggings, when the phone rang. The answering machine picked up before I got to it.

The second I heard Brad’s voice, I knew it was bad.

“Kate?” His voice was shaking. “Please be there…please pick up…you have to be here this morning, please pick up….”

I felt a stabbing in my chest and ran to find the phone. “I’m here, what’s going on? Are you okay?”

He kept saying, “I’m sorry…I don’t know what happened…” and I couldn’t tell if he could hear me or not, or if he was talking to me or not. He sounded terrified, panicked, confused, and small. He couldn’t be sounding like this. Why was he sounding like this?

“What happened?” I said. “What happened?”

“I’m okay. I think I’m okay. But I got in a car accident. I’m so sorry. I totaled the car. I don’t know what happened. I’m so sorry.”

My stomach dropped. I was holding Henry, and he squealed because I squeezed him too tight. “Are there other cars? What happened?”

“I’m okay. I think I’m okay. The police are here…they’re taking me to the hospital.” He sounded far away, like the phone wasn’t working or like my hearing wasn’t working.

“The police are taking you?”

“I don’t know, the ambulance. But the police are here.” He paused. He might have been crying, but I couldn’t be sure. “I hit another car.”

“Are the other people okay? What happened?” I was very calm. I just wanted him to tell me what happened. I felt a terrible sense of dread, but for now, I was handling this.

“I don’t know…I don’t know!”

I took a deep breath. Why couldn’t he tell me about the other car’s passengers? “I need to know how the other driver is.”

He sighed. I held my breath. “I think she’s okay. She was walking around.” I let out my breath. He was alive. The other driver was alive. We could deal with anything else.

“You hit one car? Only one? Anything else?”

“No, one car. I was driving, and the light was green, and…I was just driving, like normal, and then the next thing I remember is a boom, I think it was the airbag, and it was in my face and some guy was next to my window asking me if I was okay.”

Henry was squirming and crying. I was probably holding him too tight. Again.

“Where are you? We’re coming.”

“No, they’re taking me someplace — I don’t know what hospital. I’m at the intersection by Raley’s.” He was talking fast.

“We’re coming right now,” I said, shuffling around the house with Henry in one arm and the phone in the other, trying to find some tiny socks. “Don’t go anywhere!”

“They’re taking me now — I have to go. What? What? … They say come here and the police will tell you where to go….” He hung up. I put a bra under whatever pajama top I’d been wearing and dashed out the door with Henry and a camera and our Baby Bjorn.

I could picture the intersection in my head as he’d been talking, and I knew that both he and the other driver were at least alive and mobile, but coming up to the accident scene was more frightening than I was prepared for. This intersection we both drove through every day rose out of the horizon and was suddenly full of flashing lights and sirens and police cars and ambulances, and sparking orange flares blocking off lanes. How could this be our car out there? How could this be Brad’s accident?

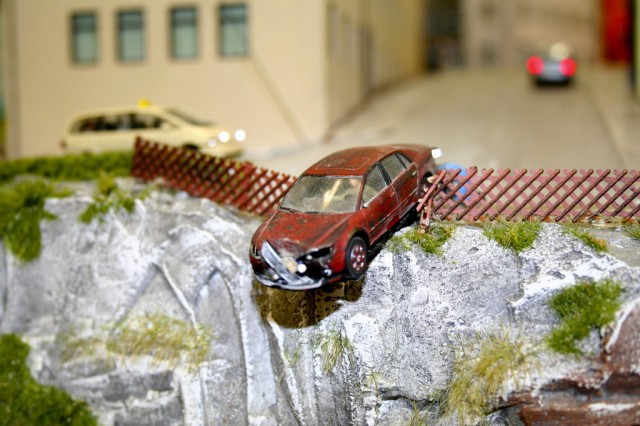

And right in the middle of the intersection was our new Prius, its entire front totally smashed up and glass shards glittering all around it in the morning sunlight. Its brand-new bumper we had replaced the month before (after I accidentally closed the garage door on it) was untouched. The cost of the new bumper: $415.

I came as close as I could get, driving in the bike lane in my little Beetle, with Henry in the carseat, waving his arms at shadows and specks of dust and flashing police lights. Traffic was stopped dead in all four directions. I couldn’t help but laugh a little bit, thinking how impressively Brad managed to mess up traffic.

A police officer came over to tell me I couldn’t be there. I was fumbling with Henry’s carseat, pulling him out and into the baby carrier I had strapped on. “I’m his wife. The guy from that car. Where is he? What happened?”

The officer nodded, and said, “Everybody’s okay,” and pointed to another officer across the wide street. I wanted to run, but I didn’t know if I was allowed to run with a baby strapped to me. Who didn’t even have a hat, I realized, on a very hot morning. I walked across the street as fast as I could without actually running, covering Henry’s head with my hands. It was a long walk in my dirty clothes and glasses instead of contacts and whatever shoes had been closest. I turned my head and looked at our smashed car, not so much because I wanted to see it, but because I didn’t want to look at the other cars. I knew that everybody stopped in those cars on my other side was thinking that I must be related to the guy who did all this. Of course the crazy-looking person who can’t dress herself or her baby properly is involved in this mess, they thought. Look at her, she can’t even put a hat on her bald baby? Maybe they felt sorry for this baby, being raised by total idiots. I kind of did. It was a very long crosswalk.

Nobody knew why Brad’s car had crashed. The officers kept telling me that although both he and the other driver had gone to the hospital, they seemed OK. I waited, taking pictures of the car and the intersection, because it was all I could think to do, until the Prius was towed away and some officers asked me some more questions, even though I didn’t know anything. I stayed in the shade of the shopping center sign with the person I realized was the other driver’s emergency contact. When I found out who she was, I kept asking if her friend was in pain or what had happened; she didn’t want to talk to me. She gave short answers and barely looked at me. When she did turn toward me, she said that her friend told her that the other driver swerved right into her lane suddenly, like he was changing lanes without looking and rammed into her. She wore her sunglasses the whole time, but I could still tell she was glaring at me underneath them. All I could say was that we were so sorry, that Brad didn’t know what had happened, that he hadn’t been trying to change lanes at all, he’d blacked out for some reason…and, I realized, he’d just had his flu vaccine. He’d never had one before. He didn’t know how he’d react to it.

While I watched our car being towed, I called my parents, to tell them to meet me at the hospital so they could deal with Henry. Then I called our doctor’s office, which I could see down the street. It was a bland office building that now seemed menacing. I talked to the nurse who’d given Brad the immunization; she said he’d been totally fine, seemed normal, hopped out of the chair and left when she was done.

“You didn’t make him wait?!” I said. She should have made him wait, even if he was fine, right? That’s what they do, isn’t it — they don’t let you leave until they’re sure you’re OK, right? But looked what had happened.

I was staring down the street at the office building, talking to it; I was so angry I wanted to run there and yell at somebody in person. “This accident happened right outside your office. Look down the street.”

“It’s…it’s not our policy…” she said. Her voice changed. She was scared. Maybe she felt bad she hadn’t made him wait after giving the vaccine, maybe she’d get in trouble, maybe the office would get in trouble, maybe we’d sue everybody. Or maybe she was just not wanting to be yelled at.

“I don’t care. Look what happened,” I said. “He left your office and look what happened.” The cost of an unexpectedly bad reaction: a car accident. I didn’t yet know what the cost of the accident would be.

I was yelling. I was upset, but I also wanted the emergency contact person to hear me, to know that I was sorry and Brad was sorry and this was not the kind of people we were, that are irresponsible and hurt others and cause problems. The nurse said she’d tell our doctor and find all the paperwork and vaccine information we’d need. I finally hung up, and after getting some info on our car, Henry and I went to the hospital.

We waited in the emergency room for a long time. It was mid-morning and empty. Henry liked watching the fish in a giant tank in the center of the room. I hoped he wouldn’t start crying. I hadn’t brought a bottle or diapers for him. “I stop and see a weeping willow, crying on his pillow,” I sang quietly as I bounced him around the room.

Henry had just started howling at the lack of a bottle when my parents walked into the waiting room. My mom was all teary-eyed, and it made me mad. I was handling this. I could not start crying right now.

I passed off Henry, instructed them to ask the nurses if there was any bottled formula they could have for Henry, and I finally got to go back and see Brad. Other than looking impossibly pale, he seemed fine. Not even any bruises that I could see. I guess the airbag did its job pretty well. “I’m sorry,” he kept saying.

“It was an accident. It’s okay.”

We figured that he’d blacked out, and that was why the car had suddenly veered into the other lane. He hadn’t been trying to change lanes at all. He was going straight through, when suddenly… he didn’t.

“I wish we hadn’t just replaced that bumper,” he said. I tried to laugh.

A few minutes later, he started to cry. “If we get sued…we could lose everything.” He covered his face. He started to shake. “We could lose everything. I don’t know what happened.”

“But that’s why we have insurance. It’s fine,” I said. The cost of our car’s insurance: $1,287 per year.

“I know, but if they think it’s my fault…they could sue us anyway….” He didn’t speculate any more. He worked with lawyers every day and saw too many lawsuits to know that it didn’t really matter who was at fault sometimes; if somebody sued you, it was expensive and painful no matter whose fault it was. And in this case, he had hit somebody for no apparent reason. But he should be covered by insurance. For a while, I tried to make him feel better. Then, after about a half hour, I got mad. At him.

“Brad, it’s oh-kay.” I said, getting tired of saying this. “It was that vaccine! You know it was that. You had it and what, five minutes later you passed out?” He nodded. “Where is the doctor? What did they tell you?”

“Nothing yet,” he said.

“They really didn’t tell you anything? Or maybe you don’t remember?”

He looked confused. “I don’t think they told me anything.”

“What if they did and you forgot?” I felt a new rush of panic and anger. “Wait, what if you did change lanes and you just forgot?” He looked confused. That didn’t help me. “What if you have, like, amnesia because you changed lanes and didn’t look and crashed? That could happen!”

“Even if I had amnesia, which I don’t, I wouldn’t have changed lanes. You know I would go straight through.” He was right. That was the way to his work.

“Well, I don’t know what you did! But if you thought the bumper was a lot to fix, this is going to be….” I didn’t finish. I didn’t know what it would be. The insurance should cover it, but the premiums would go up…to what, I had no idea. Probably a lot. “If they sue us because you ran into somebody and the insurance doesn’t want to pay because it’s so freaking weird, like if you had amnesia…”

Brad sighed.

“Yes, if you have amnesia or something and you did just swerve into somebody…. Do they have to pay?”

“I think so…I don’t know!”

“Well isn’t that why we have insurance? In case you run into somebody and get amnesia and don’t remember doing it?” I felt betrayed. Brad was supposed to know all the money stuff. And he was panicked and uncertain and that made me panicked and uncertain…and angry. With him. For not knowing, and for making me feel this way. I sat, bitter and uncomfortable on the plastic chair.

He looked miserable, more than when I’d gotten there. I knew it, and I didn’t care. “Who passes out in a car? Who does that?” I said. We were both crying when the doctor came in to say all his vitals looked normal, that he’d refer him to a heart specialist just in case, but that it seemed he passed out from a reaction to the vaccine. We nodded.

But I wondered if he had an unknown heart condition. I wondered if this could happen again. And maybe it would be a lot worse if it happened again. And I was the worst wife anybody could be. I was blaming Brad for a total accident, and I knew it wasn’t right.

That night, with Brad back home and word that the other driver was fine, I cried and cried. I was angry at the situation, but mostly I was scared about what could have happened. It was astounding that nobody was seriously injured. It was unbelievable that Brad had blacked out while driving and yet he was still here, getting Henry’s bottle ready before bed. I would get to go to sleep tonight listening to their breathing. I had never considered that might not be an option, that something bad could happen to Brad.

“You cannot do this again,” I said to Brad that night, even though I’d just also said again that it had been an accident and it was OK. “I need you here. You have to be here. I can’t handle this myself. You have to be here.” I could only say it over and over. I was so angry and scared and grateful. All I could do was cry.

The cost of the accident: a $500 deductible. But it seemed to cost much more than that.

Previously: “The Responsible Thief”

Kate Abbott recently completed the memoir Walking After Midnight, where a version of this essay appears. Her YA novel Disneylanders was published in 2013. She lives in Northern California with her husband, son, and tiny parrots.

Photo: Andrew Belenko

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments