How to Stage Your Own Musical: Steve Garvey and Jay Stern of The Bardy Bunch

Steve Garvey wrote a really excellent musical called The Bardy Bunch — a mashup of The Brady Bunch, The Partridge Family, and various Shakespeare plotlines. It premiered at the 2011 New York Fringe Fest, and Steve and director Jay Stern have been working to get it back on stage ever since.

A few months ago I attended a showcase for investors and spoke to Steve and Jay about the play’s beginnings and how these two Broadway outsiders are working the system to make their (Off) Broadway debut.

Logan Sachon: I know very little about your industry.

Steve Garvey: We also know very little about our industry! We both come from film backgrounds, but we happened to have a play on our hands, so we’ve had to learn how the theater world works. And I think that’s actually benefited us more than hurt us.

The current Off Broadway model isn’t really working. Most shows are not making their money back. A lot of the processes that are in place don’t make a lot of sense, but it’s the way people have been doing it for so many years, it’s become the norm. Coming from outside the industry, we could see the broken model with a little more objectivity.

LS: Tell me about The Bardy Bunch and how it came about.

SG: I wrote the play about two and a half years ago, mainly because I was frustrated with the film industry — how expensive making a movie is, how when you complete a script, it’s just a blueprint until someone else comes aboard and spends hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not millions, to bring it to life. But a play, even if it only shows to an audience of six people, it’s an existing thing.

So I had the idea for The Bardy Bunch, which is a mash-up of about a dozen Shakespearean plotlines set in the ’70s and involving the warring Brady and Partridge families. It came out of me very quickly, and I submitted it on a lark to the New York Fringe Festival, which is an international festival that puts on about 200 shows a year downtown. They give you a theater space. They give you a good amount of publicity because you’re under their banner. The rest you pay out of pocket.

LS: So the Fringe Festival cost you money?

Jay Stern: Time and money. I was the hired gun brought on to the show, so Steve was responsible for assembling the resources for the show. It was Off Off Broadway, so the costs are containable to some degree. But I’m always surprised by how expensive things are to do. They add up. You’re paying for the cast, the costumes, things like fire proofing your set, certain kinds of insurance. Rehearsal space is expensive.

SG: I had virtually no experience mounting a show, let alone a show with singing and dancing and a cast of 18. I went hunting for a director with some producing experience, and after meeting with 30 or so directors, I found Jay. He had the same vision I had for the show, he had the resume, and great organizational skills. Thank God. The thing with Fringe is you really don’t have a ton of time, you have x amount of weeks, very little rehearsal, and before we knew it we were up.

The show, on a very limited marketing budget, virtually no budget really, simply took off. We knew going in we had a built-in audience. We had Brady Bunch fans, Partridge Family fans, and Shakespeare. But we had no idea it’d catch on the way it did. For the five performances we were limited to, we kept selling out, and people were coming back to see it again, with their childhood friends, their sisters and brothers, to share the experience. We knew we had something, and we wanted to continue it. We wanted a commercial run.

JS: You only get five performances with Fringe, then it’s over, that’s it. And I’m speaking mainly for myself, but I think we both knew it was going to be a good show, but I don’t think we knew, I didn’t know, it was going to be quite as special as it was. I think it exceeded its expectations of quality and a real energized link with the audience. I come from a film world, and more people saw this play in five days than have probably seen my first feature altogether. And something about that was like, oh my god, there’s a real need for this show.

So we felt, we should find a way to keep doing this on our own. We had a need to get it going. So we spent about a year meeting with the industry, trying to get people interested in the show.

LS: Is that also a point of Fringe, trying to sell your show?

JS: I’m going to say no, it’s what people think they’re going to do, they think they’re going to be Urinetown, which was at Fringe, then Off Broadway, then to Broadway. But the reality is no one is going to see your show and pick it up. It’s like thinking, if my film gets into a film festival, I’m made and I’m going to Hollywood. No. It happens to one person. It’s like Brigadoon — every 12 years it happens and makes everyone think they’re going to do it.

SG: It’s like the game Frogger. You want to keep hopping forward, one leap at a time. The ultimate goal is to get all the way across to a Broadway or Off Broadway production. Fringe is a great way to move closer to that ultimate goal, but it’s unreasonable to expect anything more.

JS: So after that year of talking to producers, we found that no one wanted to produce the show. We’re unknown. We are not in the pipeline of people they know.

LS: So when you’re asking someone to produce a show, you’re asking them for money?

JS: Well, yes and no. We wanted to find a theater company or a producer, someone who could say, oh this is a great property, I want take this to a great theater. You want to sell the show to someone who will put it up, whether I’m the director or not. You’re selling the show for other people to do, that’s what we were looking for in a producer. That magical person didn’t appear.

SG: And we were surprised by that. We had our show, we had our Bradys, we had our Partridges, we had our Shakespeare. We were getting the rights to all these hit songs. We were looking at an Off Broadway run, which is maybe a tenth of the cost of a Broadway production. We felt we had a show that was low on cost but high on known commodities. What happened though is we were getting killed by our cast size.

JS: The thing that’s shocking about that is that if you look at these budgets, the amount of money spent on the cast is a drop in the bucket of the budget for the show. And the reason you want to see theater is to see human beings on stage doing amazing things and moving you. And in the case of this show, you can’t not have the Brady’s, and you can’t not have the Partridges. You can do a little bit of doubling, but you have to see the two families on the stage.

SG: There were suggestions of using puppets, or one person playing all the Brady kids, and one person playing all the Partridge kids. And that would be interesting I guess, but our show is as much an ode to the fans of the sitcoms as it is to the sitcoms themselves, and their expectations are to hear the songs and see all the characters together for the first time!

JS: You have to be true to what makes this show special. Steve’s script is really true to the emotional truth of the shows. He’s not making fun of these things, he cares about these people.

SG: It’s sort of like the way you make fun of your little brother. You love him, but you bust on him. And I think that’s why these shows have survived forty years. Their fans realize these sitcoms are kind of goofy, but there is this inherent love you have for them, and each of the characters. You grew up with them.

LS: So these meetings you were having with producers, how did you get them?

SG: Some from Fringe, some from an industry show that we did.

JS: Some through friends.

SG: We went to a couple of one-day conferences about how to produce your own play and we met some industry people. And all of them were helpful and forthcoming, but, again, once they heard about our cast size, they just told us, “Don’t even try. It can’t be done. It’s not sustainable.”

JS: And that is 100 percent true if you look at the model that they’re producing these shows on.

SG: And it’s not just producers. It goes back to Actors Equity as well! I contacted them at one point about different models that we could follow for an Off Broadway production, for example if we could do it in a cabaret club or a non-traditional theater space. And when they heard it was a cast of 18, the first question they asked was if there were any way we can get the cast size down. And I’m like, “I’m trying to hire your people! We are trying to bring them into the show!”

JS: And that’s the first thing we want to do, we want to make sure no matter what we’re doing, we can pay our amazing cast!

SG: They won the ensemble award at the Fringe Festival. They are amazing. And we wanted them. And we were telling Equity, we wanted them. When their first question is, “Is there any way you can hire fewer of the people we represent,” you know something’s wrong with the system.

LS: What is the model that they are working off of?

SG: The general rule is that a cast size shouldn’t be any more than eight for Off Broadway.

JS: And even Broadway, they try to keep it down. But the thing is, the operating costs in general are too high for what it takes to run a show. Outrageously high. So much so that tickets to Off Broadway are now $79 and higher. When I first came to New York they were $20.

But the thing is, the weekly costs are so high, and there a lot of reasons why they are and why they should be, but one of the first thing you look at is cast size, how many salaries are you paying a week.

I will say, to make a comparison to the film world, there’s not the same expectation of ever making money in theater as there is in film. I think a lot of theater people are theater lovers, it’s an art form they’re contributing to, there’s a sense of patronage in theater that there isn’t in film making. So it’s been allowed to be that way, and people expect to lose money.

A lot of the people who give to theater that we met with when we started meeting with producers were able to become theater people because they have other jobs where they make a lot of money. They don’t need to make money here.

SG: One potential investor I spoke to referred to it as a donation. There was no expectation in his mind to make his money back. But I told him a return is a very real possibility.

LS: So your hope was not to be a charity project.

JS: Our hope was not to produce it, our hope was to have it picked up by a professional theater company, and that was not happening. We realized, it’s never going to happen and the show would never happen, or we have to do it ourselves. We had to take that year to realize that was our only option, but once we knew it was our only option, we didn’t hesitate.

SG: We had a meeting with a seed money investor who had seen the show at Fringe and every few months would check in. We held him at bay at first because we were dealing with outside producers we weren’t quite sure we wanted to work with. Once we decided to do it ourselves, we called him up and set up a meeting. He offered us some money. That’s when Jay and I looked at each other and said, “Okay, before we deposit this check, do we really want to do this?” Because this was going to be the next few years of our lives. But we immediately said yes, of course.

JS: And we learned a lot about this industry, how it works. It’s stacked against outsiders in a way a lot of things aren’t. And we had to learn that. And we had to learn that if we weren’t going to go the traditional means, we had to really think outside. The film industry is very different that way. In the independent film world, there are so many ways to get a film made. Not so in theater. And it costs less to make films. I could make six features for the price it costs to put on a play.

LS: Why is that?

SG: It’s a few things. Theater space for certain. Just the difference between doing an Off Broadway show downtown in the Village, which is where we’re looking, versus midtown is the difference between $7,000 a week and $25,000. Just for space.

JS: And that’s not including that theaters get 5% of your box office, which is standard.

LS: So how much is it going to cost you a week to put on this show? Do you know yet?

JS: Some costs are not flexible. It costs the same to run an ad in Playbill if you’re a million dollar Broadway production or you’re a Fringe show. You have to have a production office, you have to have a stage manager, you have to have lawyers, an accountant, and you have to get people who know what they’re doing, you can’t get a part time person to do this.

LS: How much of the cost of your particular show is the licensing?

SG: Very little, actually. Getting the music ended up being pretty easy. We had to hire someone who knew how to get clearances, but that was almost a nominal fee compared to our budget, and the money spent on the songs themselves is a royalty, a percentage of the box office.

JS: And because we’re producing the show, Steve is providing the script to the production. If we were being hired to do it, we’d be paid a rate. Instead, we’ll get something in the backend. So our number one creative expense was the publishing rights, which ended up being fairly simple.

LS: So you met this investor, and he gave you an amount of money?

SG: And just said, let me know what you’re doing with it. So we got the music rights guy, we got an attorney, and we got a general manager. And that’s where the first chunk of seed money went. And through the attorney and the general manager we put together a budget, set up a strategy, set up the operating costs, set up a recoupment forecast so our investors would know when to expect their investment to pay off.

JS: The general manager runs the production office, puts the machine together. We don’t have to worry about accounting necessarily or worry about budgets. The person we got has done a lot of Broadway and Off Broadway, has done some producing as well. One reason we liked him so much, is he never once asked if we had to go Equity. Of course we’re going to go Equity. He knew we needed the cast size, and he thought there might be a model we could do this.

SG: He got that we wanted to produce the show, not a date. It wasn’t a case of “we have to do this in the fall or else.” It’s a long-term development.

LS: And you pay him a salary?

JS: He’s basically on retainer, and once the show opens, he’ll get a weekly rate as part of the operating budget.

LS: So the showcase I saw, how far after your initial seed money was that?

JS: It was about a year between the first money and this showcase. But now we have the production model, we have the song rights, and we have a production plan, should we get the money, on how we want to roll it out. So this was a chance to show it to our investors, for them to bring people with them, get more interest.

LS: Tell me about the model you came up with.

SG: We decided early on that we wanted to do the show downtown, since it’s essentially a Village show. And it wasn’t long before we determined that an eight-performance-a-week format in a traditional space made the most sense for us (in part because, yes, the cast size). Then we worked for weeks and weeks and weeks with the GM on the budget. The first one he sent, we had tons of questions, most because of our inexperience. We thought, “He must be rolling his eyes at us.”

But he was very patient with us. And I think over time, some of our naïve questions actually pointed out some commonly budgeted items that maybe don’t need to be budgeted for. There was a line item for an opening day party, or in other words, a party for investors that investors are paying for themselves. So we’d go back to our GM and his team and say, “Maybe we don’t need to be paying thousands of dollars for this.” And they were like, “Yeah, you’re right. We don’t need that.” So, it was a two-month back and forth, line item by line item process, and we got to the point where we felt we had a lean mean fighting machine, half the budget of most Off Broadway shows.

JS: And we looked at budgets that were similar in type to ours.

SG: And one thing we discovered is, while we wanted the tightest budget possible, some areas are better left alone. We initially knocked down our advertising budget considerably, only to be told by money people, “What are you doing? Spend more money on advertising!”

LS: So where are you right now?

SG: We are meeting with people, gauging their interest, and seeing how much of an investment they want to put in the show. Our focus, as far as the recoupment forecast goes, is to think beyond New York and look to the long-term goals of licensing the show. Because really, the show could play in any city in America, and any country where the shows were in syndication.

JS: A lot of shows you look at your New York run as your loss leader, so you’re getting your show, you’re getting the buzz, you’re getting attention, you’re letting it run long, and then you license it and make it a cheaper model, and that’s where the investors get their money back. Steve and I happen to think we can run this in New York and make a profit here. But the position for investors is, we really think there’s a good long tail here.

LS: It’d be amazing in high school.

SG: Right? Everyone gets a part, every character has their standout moment, which is what you really want. And it has Shakespeare! So it has an educational element. We want to get to Shakespeare festivals, too. We want to go to the Globe!

LS: How much are you working on this right now? You both have other jobs.

SG: I’m a copywriter for ad agencies and marketing agencies, which is why we wanted to cut down our advertising budget as much as we did because I know how much of it can be cut! So that’s what I do probably three days out of the week, and the other two are highly concentrated on trying to get this up.

JS: I work for a company that makes high brow novelty items. Like Freudian slippers. I work there four days a week and I have a feature film in post production that I’m trying to get done by this summer. And I also direct stuff in theater.

LS: So you’re just not doing anything ever.

SG: I almost didn’t hire him because, when I was interviewing him, he was just so busy! I was like, “When are you going to find the time! There is a cast of 18, there’s music, there’s dancing!” But that’s the thing. Jay can wear many hats and pull it off. I’m a single hat guy.

JS: This is the priority project. It’s been in the front of our minds for a year, even in the down time. I think it’s something that we as people really have to do. This show is bigger than us. It needs to be seen.

SG: I feel it is, too. I grew up with The Brady Bunch and The Partridge Family, and I know for a fact that if this show existed and I had nothing to do with it, I would be sitting in the front row on opening night. And that’s what drives me. I just know there are people that would have to see this show.

LS: Can we talk about asking for money? Is that something you had experience with before this?

JS: I had, for my movie. I raised money over several years for that, through donations and investors. So I’d been through that before, and this is a different thing. We’re actually going to strangers, we’re going to people who are committed to theater itself. People who saw the show at Fringe, who have been to a reading, it’s easy to ask for money — it’s not for me, it’s for the show, and they give money to shows.

It was harder to ask for money for the film, because it was really money for me, and why do I need to make a movie, why does anyone need to make a movie. But now, this is bigger than us. We are fighting for us, we are fighting for the cast, for the people who kept coming back. So we’re fighting for that idea.

SG: I think how we’re going to get our money is going to be people who are fans of the Bradys and Partridges who like theater but maybe aren’t theater investors — because theater people look at our budget and are like, you have an 18 person cast, you’re nobody, what, where’s your advertising budget, where’s my opening party?

JS:People who invest in many ways are buying access. They are a doctor, or whatever, and they’re buying the chance to come to auditions, to come to rehearsals, you’re buying the chance to be in the theater world, to be in showbiz, and in our world, an investment of a thousand dollars means something that it doesn’t for a Broadway show. The access to entry is lower, and the return is higher. And you have fun, you get to meet the cast, and that’s the kind of people we want to attract.

SG: Our seed money guy came to the rehearsal and you could hear him singing the songs — that’s the kind of people that are attracted to the show, they know it’s a passion project, and they’re into it, too.

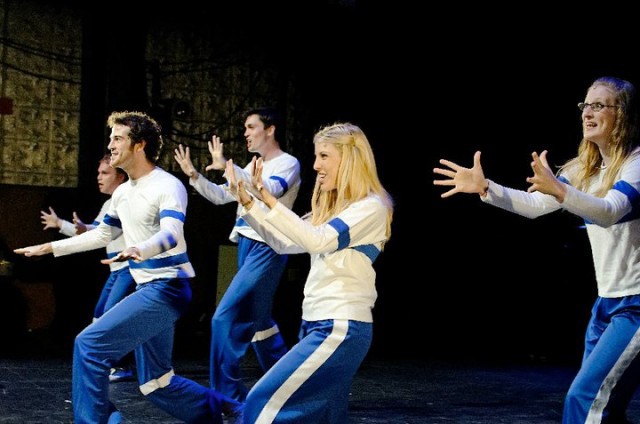

Photo by Tom Henning, courtesy of The Bardy Bunch.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments