I’m Not a Bartender, I’m a Bar-Back

by Brendan O’Connor

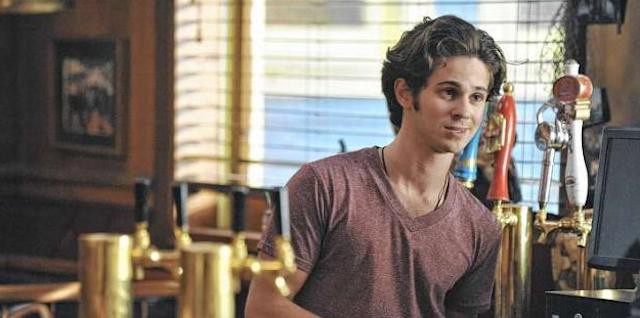

I work in a bar. I’m not a bartender, I’m a bar-back, which is like being an intern. I’m also an actual intern, at an office, in the city. But that’s for the future, for experience. This is for now, for the money. The bartenders call me “NFG” — “New Fuckin’ Guy.” It’s mostly a term of endearment, except for when it isn’t.

The duties of the bar-back: Wash the glasses; refill the ice; get wine and beer and liquor from the basement; change the kegs. At any given point during the busiest parts of a night at work, two or more of these things needs to be have already been done.

Sometimes, if I’m lucky and all the bartenders are busy and there isn’t a manager around, they let me pour someone a beer. This is always very exciting. I’m not allowed to handle the money, cash or card, because that would be way too much responsibility for a 23-year-old. The bartenders themselves always take care of payment. They take the order, place it, ask me to pop a Budweiser for Tony or pull a Coors for Don and move on to the next thing.

On busy nights I don’t stop moving for about five hours. The next two to three are spent restocking and cleaning up. I walk out the door with cash in my pocket. I’m supposed to get a paycheck as well but the bartenders told me I’ll never see it. I don’t even know what my hourly wage is supposed to be. On really busy nights I can make as much as 130, even 140 bucks, handed to me as a wad of cash as I walk out the door after sharing a beer or three. Not bad for a seven hour shift, more or less.

The bar is attached to a restaurant, the kind of place that, though the walls are more window than wall, never gets any brighter than it is at four o’clock in the afternoon, even in the summertime. Everything is the heavy, dull brown of fake wood. Servers come from the restaurant side and wait impatiently for drinks to be made and don’t say thank you when the bartenders mix six mojitos in as many minutes. (The only thing the bartenders hate more than the servers is making mojitos.)

The bar itself is a long, narrow rectangle with a single point of egress in the middle of one of its longer sides. Standing behind any bar, one has the feeling of being on stage, the center of attention. Everyone is, after all, looking at you. Or, at least, their stools are originally oriented in your direction. But working behind the bar you realize that you are not really on stage at all, that despite your inescapably public position, you are in fact utterly invisible, and bar-backs doubly so. (“Can you make me a drink?” “Sorry, no, let me just grab — “ “Well then you’re just taking up space back there, aren’t you?”)

Standing behind the bar, washing glasses, invisible, I hear a lot of talk. A lot of ignorant talk. Obama is a Muslim. Obama was born in Kenya. Derogatory things about women. Derogatory things about minorities. These are times I wish to be on the other side of the bar — to start a discourse, to say no, you’re wrong. To say anything. It’s an extremely difficult task of keeping all of that to myself. What a privilege it is to be able to speak your mind. What a privilege to be able to say, “You are not only wrong but also ignorant and offensive.” What a privilege it is to be able to say what one is thinking without fear of reprisal — of losing your job.

But I’m new. I have it easy. You would not believe the amount of disdain bartenders hold towards their customers. The bartenders are all at least 10 years older than me, and they’ve all been working in restaurants and bars for at least that long. Ten years is a long time to not be able to tell someone who drops the N-bomb to get the fuck out.

Twice I’ve been told to smile more by customers. (The bartenders don’t care if I smile.) The first time was a pair of little old ladies who first asked me my name. “Brendan O’Connor,” I said. They were pleased with that response because they had thought that I’d looked Irish. I smiled at that and they cackled and cooed even more and said, “There’s that Irishman’s smile! You should smile more!” (It’s hard to be disdainful towards little old ladies with an eye for the Hibernian.)

The second time someone told me to smile more was on Thanksgiving Day, about halfway through the 12-hour shift I got conned into working. (Easier, then.) I made $180.

Everything is run through computers at this bar. Food orders, drink orders, everything. The system is clunky and old and, to my web 2.0 sensibilities, quite offensive. There is a screensaver with the name of the bar bouncing around a black background. It never touches the sides.

When the computers crash, which they sometimes do, nobody can place an order or pay for anything. Not by card, not by cash — the registers are all locked up, it’s all integrated into the computers. When the system does eventually come back online, any order that was still open at the time of the crash is lost and will need to be re-entered, usually after confirmation with the customer about what was ordered. Used to the computers, the bartenders never remember. The longer the computers are shutdown, the more reedy and frantic the tone of people’s voices looking to pay their bills gets. In this moment of chaos, even with the knowledge of what a pain-in-the-ass it is going to be to figure everything out once the computers are back up and running, I can hear a distinct sense of pleasure in the bartender’s response to the litany of can-we-get-the-check requests: “No.” I keep washing glasses.

Down the street there’s a small place where they do everything by hand. There are no computers, no crashes. Someone writes down your burger-and-a-Long-Island order — it’s always a burger-and-a-Long-Island — on a piece of paper and it gets passed around, and 10 minutes later you hand over your 13 bucks and everybody’s happy. I know I am.

Brendan O’Connor lives in New York.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments