Entitlement, Defined

A friend and I made a new friend at the bar last week. He was a loud, gregarious, narcississtic man who described himself as independently wealthy and told us tales of his juvenile delinquency — just the kind of person you want to meet at a bar if you are in the mood to meet a person at a bar. He offered to drive us to a second location, but we demured (never go to a second location, and also, one of the great perks of living in New York City is never having to worry about the intersection of drinking and driving).

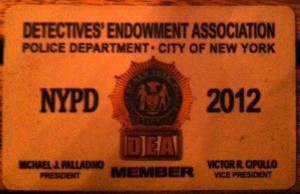

“No thanks,” we said. “Oh you’re worried I’ll get pulled over!” (Which, no, we’re worried you’ll plow down a crosswalk of pedestrians.) Alas, he was ready to refute our doubts: “I can’t get in trouble. I have … THIS.” He whipped out a card.

“This” was a card from the Detective’s Endowment Association, with a homicide detective’s name and badge number written on the back (supposedly). “Anyone who could ever pull me over, this guy” — pointing to the name scrawled on the back — “outranks him. They don’t want to call him up to bother him, so I get off.” It sounded sort of plausible. (I’ve watched TV.)

“Did you buy that?” I asked. “I don’t need to buy that,” he said. “This is how it works with you have money. Friends, family, and powerful people get these cards.” “Have you used it?” “Sure,” he said. “Lots of times.” Mostly traffic violations, he claimed, though he said that he could murder someone “in this bar right now,” stay at the scene, and that this card would get him off. I did not believe him. But he believed himself.

(The cards are a real thing, though their efficacy is dependent on the method of attainment, e.g. bought on ebay, not effective. The card, according to the NYT, “starts a conversation.”)

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments