Adventures in Negotiation: A Hubcap, A Tire, And A Car

by Brian Blickenstaff

When I pulled in through the chain-link gate and parked in the small dirt turnabout, the only person in sight was an overalled, middle-aged white man, whose size and demeanor brought to mind Lennie Small, the Steinbeck character. He was sorting hubcaps. The yard was full of them, stacked on racks and piled in heaps. I needed one, and I hoped Lennie could help. I was at Cadillac Corner, a junk yard and something of a cultural landmark in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. In Mississippi, junk yards are not hard to find. But while most junk yards are, well, yards full of junk, Cadillac Corner deals almost exclusively in hubcaps, thousands of them.

I’d come because last summer, the rear, drivers-side hubcap spun off my ’06 Corolla somewhere between Chicago and St. Louis. Under normal circumstances, getting a new hubcap is something I could procrastinate on for years. But these were not normal circumstances. This was April 2nd, 2012. On May 15th, my wife and I were moving to Germany, where she’d recently accepted a job. We were liquidating our American life. I needed to sell our car, but first, I needed a new hubcap.

Here’s the thing about hubcaps: They have immense aesthetic power. Remove just one and you can make an otherwise well maintained car look like that jalopy your friend drove in high school — the one with the rust and the chipped paint and the missing hubcap. A car with three hubcaps is probably worth $1,000 less than the same car with four. Online, I’d found some for my car’s make and model, but they were mostly sold in sets of four, for $200. The single hubcaps I encountered on Ebay cost around $60 each. I figured Cadillac Corner could beat $60.

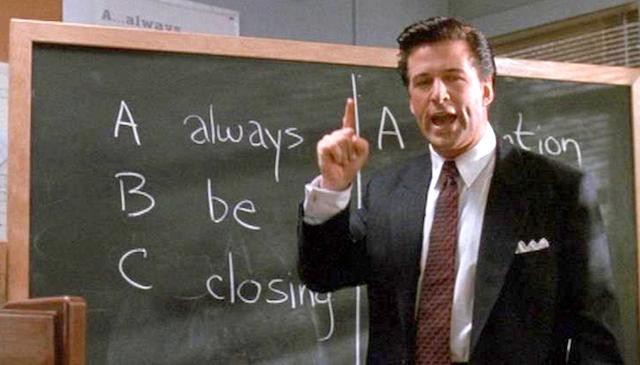

I had an ulterior motive for visiting Cadillac Corner too: I was selling my car on Craigslist and I wanted to learn to close a deal. Or, in any case, I needed some practice negotiating. What better way to practice than haggling over parts in a junk yard? I tend to be a timid negotiator, which probably leads me to lose out on most deals. I wanted to learn to be stronger under pressure. I wanted to learn to win.

I’d recently listened to Slate’s series of podcasts on negotiation, and I had some ideas about how I could take my game to the next level. I was eager to try what I’d learned. According to Slate, once a financial negotiating grinds to a standstill, one can still achieve a better deal by negotiating for things other than money. In my case, I’d brought a used tire with me to Cadillac Corner. I hoped to use it to sweeten a deal.

When I hopped out and waved, Lennie looked at me and then glanced toward the trailer, which sat by some trees in the back of the lot. No one was there. A look of worry crept across his brow as he turned toward the mechanics’ garage and its adjacent pile of tires. Still nobody. He was alone. I told him why I’d come. He mumbled something about asking the boss, walked toward the trailer and disappeared inside, leaving his loaded dolly right where it stood.

When he reappeared, he told me I needed to speak with Don and motioned for me to follow him over to the mechanics’ garage. Inside, three men lay on the floor, peering under a vehicle. When we walked in, they looked up at us all at once, and there was an awkward beat in which Lennie and I waited for one another to speak. When I eventually asked for Don, a previously unseen fourth man emerged from behind a nearby support beam as if he’d been hiding there, waiting for us to make our move. He looked about sixty-five, was slight in stature, and wore a days’ old, porcelain beard. This was Don. He seemed nervous.

I pointed to my car, explained the situation. Don walked across the yard to a series of head-high bookshelves filled with hubcaps. Near the fence, he stopped, reached up, and, like a veteran librarian searching for an obscure text, pulled down my Corolla’s exact hubcap. If my memory serves, he didn’t even look to see if he were grabbing the right one. He just knew.

“It’s twenty dollars,” he said. “You want me to put it on for ya?” Cadillac Corner is full service.

Something about the way he said, “twenty dollars,” and then went to work on my wheel seemed final and nonnegotiable. I wanted to counter-offer; I wanted to say “sixteen,” but I couldn’t. I chickened out. I just took a deep breath and slowly exhaled.

As he crouched and snapped the hubcap on, I remembered the spare tire in my trunk. This was my chance. I figured the tire was worth at least twenty dollars, maybe more. I would settle for an even trade, I thought. I popped the trunk and had Don evaluate it. He turned it over in his grease-blackened hands, feeling the barely-warn treads, thinking. Then he left for the trailer. Like Lennie, he had to ask the boss.

When he reappeared, he shouted across the yard: “Four dollars.”

“Four dollars?” I repeated, dumbly.

“Four dollars.”

I knew I was getting taken on the tire, but, on the other hand, I needed to get rid of it. I couldn’t bring it to Germany and I’d considered throwing it away before I realized I could probably sell it. Plus, $16 seemed like a deal on the hubcap. I shrugged, handed the man a twenty and took my change. But I knew I could have done better. I knew I’d failed in the negotiation. I didn’t know the value of the items but Don and the boss did. They were experts. I hadn’t done my research. Always do your research.

After showing the car half-a-dozen times, I stopped placing too much hope in potential buyers. I think some people shop for cars for fun, like others go to the mall just to pass time. By late April, I began to worry we wouldn’t sell our car before we left. But then, on the first of May, my phone rang. I was on my bike when I felt it vibrate in my pocket. A week before, I showed the car to a young couple form Columbia, Mississippi, a fulltime student and an offshore oil rig technician. I was excited to see their number on the phone’s screen. Nobody had ever called back before.

The oil worker didn’t waste any time: “What’s the lowest price you’ll take?” he asked. By now I’d analyzed and learned from what had gone wrong in my hubcap deal. I’d researched my car’s value and knew what I wanted for it. Most importantly, I’d set everything up so I was in control. I’d intentionally listed the car for a higher price than it was worth — at $8,800 instead of $8,300 — hoping a counter offer would align with the car’s actual value. Furthermore, I’d learned the importance of being the first to name a price. With my asking price already on Craigslist, I could anticipate the counteroffer instead of negotiating my way up from a buyer’s initial offer. But I wasn’t prepared for the oil worker’s question. He’d basically asked me to lowball myself. If I answered honestly I knew he’d make an even lower counter offer.

I stuttered for a moment, wondering what to say. Finally, I told him to “make me an offer.” I think my voice cracked. “I’ll give you $7,500,” he said.

I started to panic. This guy was good, and his offer was way below what I really wanted for the car. “How about $8,200?” I countered. My anxiety was screwing with my self-confidence. I sounded weak, I thought. Why couldn’t he have called when I wasn’t on my bike, when I had my notes in front of me? He sighed into the phone and didn’t say anything for a moment. “What about $7,900?”

This was progress, but it wasn’t good enough. The Slate podcast suggests coming up with limits before entering into a negotiation so you don’t get caught up in the excitement of the back-and-forth and accidentally deal below (or above) what you’re willing to earn (or spend). My wife and I had agreed that $8,000 was our low limit, and I told the oilrig worker as much.

He said he had to talk it over with his wife and we hung up. We’d come to a temporary ceasefire. As I got back on my bike I couldn’t tell if by holding firm on my limit I had done well and was now in control of things or if I’d just destroyed the sale over a $100 disagreement. Later, I explained everything to my wife. “Why didn’t you just take $7,900?” she asked, as though she thought I’d lost my mind. “You’re right,” I said.

Sometimes negotiations aren’t about getting the perfect deal but about getting what’s best under the circumstances. With our impending move, it was more important to have $7,900 in our pockets than it was to wait for the best offer, for the $8,300 we thought the car was worth. I called the oil worker back. He sounded relieved. But when I hung up, I couldn’t help but wonder. Maybe I’d called him when he’d been having the same conversation with his wife. Maybe if I’d waited…

Brian Blickenstaff is a writer based in Heidelberg, Germany. He lived in Mississippi for six years. He has written for Slate, ESPN and the Classical, among other publications.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments