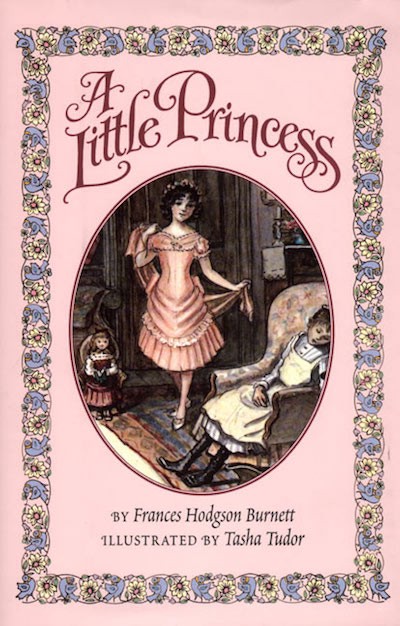

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Frances Hodgson Burnett’s ‘A Little Princess’

This book inspired way too many of my life philosophies.

A Little Princess was such a huge influence on my life that I barely know where to begin. The whole “if you have a job to do, even if it is hard/uncomfortable/disgusting, you need to do it without complaining” ethic comes directly from this book.

The bit about “you can still behave like a princess, no matter what you’re wearing or what work you’re doing” was a huge part of how I carried myself during my entry-level jobs, to the point where, at one food service job, I earned the nickname “Princess” without ever saying the word myself. (The head cook argued on my behalf, saying I was the only one willing to regularly do the gross prep work, like squirting butter into little black plastic bowls, which is also something I probably picked up from this book.)

Also, there’s kind of this message that if you have a certain kind of voice and speech pattern, you’ll get opportunities that other people don’t, and I should probably drop this link here, once you open up the page you can pull the little slider to -41.35 to hear my voice:

SAN DIEGO COMIC-CON: Obsessed Ep 119

So… yeah. This book influenced so much about how I approached the working world, and how I decided that I, too, would behave like a princess no matter what. (The results were hit-or-miss. Certainly behaving “like a princess” helps when you’re a receptionist, and even when you’re a telemarketer. It also means you’re the one who always cleans out the employee fridge.)

If you are not familiar with A Little Princess, here’s the recap: Sara Crewe is a smart and wealthy young girl who is dropped off at a boarding school in England so her father can go back to India and pour his money into dubious investments. He loses every penny, then dies of shame and malaria. Miss Minchin, the boarding school’s strict proprietress, tells Sara that she must work for her living now, and she can start by working directly for the boarding school. (Also, she’s not going to get paid until she works off her father’s debts to the school, and that’s going to take a long time.)

Miss Minchin and the boarding school staff work Sara mercilessly and deny her food just because they can. Sara, meanwhile, vows that she will do every job to the best of her ability, and she will act like a princess no matter how poorly she is treated. She also charms the next-door neighbors, who recognize that she is not an ordinary servant because of her posh accent. The Indian man who works next door discovers that Sara can speak Hindi, and then decides to surprise her by secretly redecorating her attic bedroom while she is sleeping. (This is not creepy.)

We learn—surprise, surprise—that the next-door neighbors were also involved in the same dubious investments as Sara’s father, except one of the investments paid off, and now they’re all super-rich, and they’ve been looking for Sara for two years so they can tell her she’s super-rich too. Sara transitions back into the life of luxury, and also spends a chapter checking up on the less-fortunate friends she made while she was poor, making sure they have enough to eat and a roof over their heads, because that’s what a princess does.

The past couple of installments of this series have been about books that are outside of my cultural experience, and because of that I’ve been very aware that I am discussing them from a limited perspective.

But I spent a lot of my childhood identifying directly with the characters in A Little Princess, and part of that might have something to do with the fact that Frances Hodgson Burnett’s family moved to Knoxville, Tennessee when Burnett was 16.

Yes, y’all. Our beloved British author spent her adolescence and early adulthood in the American Midwest (or American South, depending on where you put Tennessee), probably picking up a whole ‘nother layer of guess culture and “feelings don’t get the chores done.” I’m making a joke about this, because I haven’t done enough research to know what Burnett’s life or family culture were like at all, but to a little girl in the rural Midwest in the 1980s, Burnett’s perspectives on work and behavior felt really familiar.

I referenced A Little Princess when I wrote about Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, because both of them include similar scenes: a child, who is extraordinarily hungry, finds money on the street while standing directly in front of a place that sells food.

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Roald Dahl’s ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’

Charlie decides to buy one Wonka bar and take the rest of the money back to his family, but his hunger and greed overwhelms him and he buys a second Wonka bar, which just happens to include a Golden Ticket.

Sara uses her money to buy six buns (she can only afford four, but the baker gives her six, probably because of her polite behavior and her posh accent) and then she immediately gives five of those buns to a beggar girl who she assumes is hungrier than she is.

I used to believe, like Sara, that if you had something it was your job to give as much of it to other people as you could. Even if it meant your needs didn’t get met. I don’t believe that anymore.

We have to address the Becky Problem, of course. Becky is the scullery maid at Miss Minchin’s Select Seminary; she and Sara become friends before Sara loses her fortune, and they work side-by-side afterwards. At the end of the story Sara is adopted by next-door-neighbor Mr. Carrisford and—that very afternoon—writes Becky a letter inviting her to become her “attendant,” or a kind of junior lady’s maid.

Why is Becky not invited to become Sara’s adopted sister? Sara says, multiple times throughout the book, that she and Becky are just alike; they’re both “two little girls.” So why does Sara become a rich heiress and Becky become her attendant?

There are a couple of different ways we can read this, but the way that makes the most sense (to me) is the idea that Becky’s move up in the world is as significant as Sara’s. Becky has no education and barely any training. Miss Minchin states, in the text, that she hired Becky at well below the standard wage because she knew the young girl had no other options.

Becky would never be in the position to be an attendant, or to have the chance to become a lady’s maid (which is a legit career that comes with its own financial benefits), if it weren’t for Sara. Becky is not given the opportunity to become an heiress, but she is given the opportunity to develop a marketable skill and improve her own finances and prospects—which is her own, and equally valid, Cinderella story.

The problem I always had with the Becky plot, BTW, wasn’t that she ended up as a junior lady’s maid. It was that Ram Dass, the Indian man who sneaks into Sara’s room at night to give her warm blankets and food, doesn’t give Becky the same comforts. He knows Becky lives in the room next to Sara, and he knows that both of them are going to bed cold and hungry. He has been secretly watching the two of them (in a totally non-creepy way) for weeks, and he’s discussed this “let’s give Sara something so she doesn’t freeze or starve” plan with his employer, and neither of them say “hey, maybe we should give that other girl something too.”

I was also always a little disappointed in Sara when she gives Becky her old blanket and pillow instead of sharing her new stuff. I don’t know exactly how many bedding components Ram Dass added to Sara’s bed, but if he gave her two new pillows and she gave Becky one old pillow, then I am ashamed, deeply, of ever wanting to be like her.

The 1995 film version, directed by Alfonso Cuarón, changes up the story by setting it in America, pushing it into the 20th century, and keeping Sara’s father alive (he just goes missing for a while, something something WWI) and by having Mr. Crewe adopt both Sara and Becky after he returns. It also changes the story by removing the “dubious investment” plot; we no longer see Sara’s father trying to get richer quicker by throwing his cash into a literal hole and hoping diamonds come out.

I do not like the Cuarón version. That famous scene where Sara says “all girls are princesses” completely misreads the story. (The whole point is that you’re supposed to try to live up to your own ideal of what a princess would do—and keep in mind that we’re talking about stiff-upper-lip Victorian-era princesses, plus Sara’s desire to be as unflinching as Marie Antoinette as she was being led to her death—not that you’re a princess by default.) I don’t like the Shirley Temple version either, which also eliminates the dubious investment plot and has Sara find her still-living father with the help of Queen Victoria, but at least it got the time period right.

My version is the London Weekend Television miniseries from 1989 (which is also the one they showed on PBS), the one that stays true to its source material, including the swallowing of emotions and gritting of teeth and all of the scenes where adults talk to solicitors about money. A Little Princess has its fairy-tale ending, with the magic of waking up in a newly-decorated bedroom and finding out that you are richer than you ever imagined, but the part of the story that matters most is the realism. The decision to face your circumstances and deal with them. To get the work done because you have to; because until you have money, you have a very limited set of choices.

The last chapter of the book, titled “Anne,” is also a realistic one. Sara goes and visits the bakery where she once bought six buns, and learns that the baker has given the beggar girl both a job and a room above the bakery. This is another rags-to-riches story, by the way. Anne will never be as rich as Sara, but she’s not homeless anymore. She can earn her own money, which is a privilege that Sara never had for herself. Her happy ending is just as important—both for her, and for the rest of us who will always need jobs, even if we sometimes pretend we’re princesses while we’re doing them.

Previously:

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: George Ella Lyon’s ‘Borrowed Children’

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments