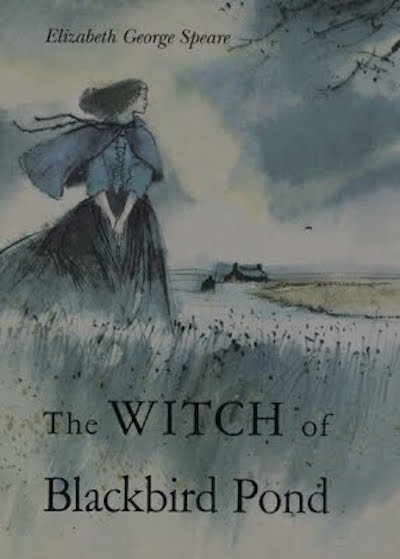

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: ‘The Witch of Blackbird Pond’

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Elizabeth George Speare’s ‘The Witch of Blackbird Pond’

Life is about spending time with the people you love and about solving your financial problems through marriage.

So I never liked this book as a kid and I think it’s because nothing really paid off. For starters, the title implies that our heroine, Kit Tyler, either is or will become a witch, which of course is not the case. (Young Nicole was hugely disappointed.)

Once you get partway through the book and realize “okay, it’s going to be about witch trials, not actual witches,” you start expecting some kind of big dramatic sequence where the townspeople toss Kit into the water and she has to decide whether to sink or swim. Speare sets this up right at the beginning, when Kit jumps in the water to rescue Prudence’s doll and everyone is astonished that she can swim; surely if you’re going to put Chekhov’s Dog Paddle on the table, you have to bring it back at the end of the story.

Worst of all, Kit’s thoughts on slave ownership never change. Sure, this is a realistic story and a young girl in the 17th century might have treated slavery as a given, but it’s also a children’s book and you kind of expect a change of heart. If you open the novel with a character wishing she hadn’t had to sell her personal slave in order to book passage to the New World, you had better have that character eventually say something like “Wow, owning a person is a really weird concept when you think about it. When I’m grown up and have money of my own, I’ll never have slaves again.”

Now that I’ve set up that segue, let’s talk about money.

Kit makes the long journey from Barbados to Connecticut because her immediate family no longer has money; after an overseer mismanages and possibly embezzles from the family’s plantation, and after Kit’s grandfather (her only guardian) dies, Kit sells off the remaining assets to pay her grandfather’s debts, sells her personal slave to book passage on the Dolphin, and shows up at her aunt’s farm in Connecticut unannounced.

Which—wow, Kit. Not cool.

Then we get a long sequence of “formerly rich girl discovers how hard other people work,” which is kind of a trope and lacks even the payoff of Kit taking pride in her new skills or in her increased physical strength. All she can think about is the day when she’ll be rich again and be able to have other people do this work for her.

As a child, the scene that most stood out for me was the one where Kit opens her seven trunks and shows her cousins all of the beautiful dresses she has brought from Barbados—dresses which the reader quickly understands she will no longer be allowed to wear, since they won’t be appropriate for her new life. Even this is a bit of a trope; you see it in A Little Princess and Gone With the Wind and in Speare’s other well-known book, Calico Captive: the privileged young woman being forced to adjust her identity by setting aside her past self’s clothes. (One of the reasons this scene resonates so much is because a lot of us go through it as adolescents and young adults; our changing bodies and changing responsibilities mean having to set aside our favorite outfits because they either no longer fit or are no longer appropriate. Think of the opening of Spring Awakening. For that matter, think of the Book of Genesis. Unwanted but inevitable responsibilities accompanied by a mandatory wardrobe change.)

By the end of the book Kit is ready to sell all of those beautiful clothes to earn enough money to set off on her own and find work as a governess. It’s appropriate, because it acknowledges that her life will never be what it was on her grandfather’s plantation in Barbados; it’s also appropriate because teaching is the one new skill at which Kit excels. (She’s never going to be a natural cook or farmer or seamstress.)

But even that doesn’t pay off. Instead, a man shows up with a marriage proposal.

Obviously Nat Eaton is the guy Kit is destined to fall in love with, that’s the one plot point that does in fact deliver what it promises, and the fact that Nat has a new boat and new clothes and the ability to provide for Kit helps make her decision easy. (Imagine if she had to decide whether to marry the Nat who only owns one pair of breeches and who works as a first mate on his father’s ship.)

So we learn, by reading this book, that life can be hard at times; that you can lose a beloved grandfather and have to sell a personal slave, that you can arrive unannounced at your relatives’ home and then become frustrated with the amount of work they ask you to contribute to the household, that you can survive a witch trial and the loss of your fancy clothes, and that life is about spending time with the people you love (as the Witch of Blackbird Pond—who isn’t even really a witch—teaches Kit) and about solving your financial problems through marriage.

Now it’s your turn to tell me all of the parts you loved about this book, because I know a lot of you did, and I’ve been a little less-than-gentle with its contents.

Next week: The Boxcar Children.

Previously:

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Katherine Paterson’s ‘Jacob Have I Loved’

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments