More #RealTalk From Men About Income, Savings, Debts, Etc.

Male honesty around money: it’s a trend!

Neal Gabler’s confessional Atlantic essay about being broke, the one I linked to in my “$400 Emergency” post, really seems to have struck a chord — not merely on Medium but in general.

The reaction, naturally, has been mixed. Our friend Helaine Olen rolls her eyes at Gabler for wallowing.

Many of us are in financial trouble and are too ashamed to speak about it. It’s easy to identify with Gabler’s woes, especially if your own upper-middle-class life feels crunched. Combine that with the unyielding popularity of financial rubbernecking (as any personal finance writer can tell you) and you have internet gold.

Gabler’s essay is the latest example of the long-standing genre that I like to call all the sad, broke, literary men. It almost always presents a personal anecdote as an emblem of broader woes, holding up the author as a symbol of our seemingly forever-contracting middle-income economy. But all too often, it is simply a disguised narrative of privilege.

Gabler’s fellow Atlantic contributor Noah Berlatsky manages to gin up a bit more sympathy.

more and more, the connection between the giant platform and the decent living is disintegrating. You can write a viral post about working for poverty wages at Yelp! on Medium, and get paid nothing for the pleasure of seeing everyone talk about you. You can have thousands, or tens of thousands, of followers on Twitter, where people follow your 140-character posts, even if you don’t get paid for writing, and/or don’t have much of an income.

I’m more financially stable than Gabler, as far as I can tell. That’s because (a) my wife works fulltime, (b) I do a lot of work for hire scut jobs sans byline or much in the way of creative input. Gabler has achieved a number of my career goals. But, in the current environment, those career goals of peer respect, audience, and industry accolades are only weakly correlated with income. As writing content becomes crowdsourced, being a known and respected writer has less to do with being a solvent one.

The timing may be a coincidence, but, in light of these ongoing discussions, I appreciate getting to hear more honest stories about finances from men via Esquire — not a publication I associate with gritty realism. David Walters sat down with four guys, aged 25–48, each representing a different income bracket, and asked them probing questions about their savings, their debts, and their plans.

The oldest fellow in the group makes $53,000 a year and is married with three kids. When Walters asks him what his family needs that he can’t afford, his answer is a house: “A ranch-style home, four to five bedrooms, two to three bathrooms.” Similarly, the answer to what he wants and can’t afford is a car, ideally a roomy Volvo. While he’s trying to save for college for his kids, he’s also still paying off his student loans (“I think I still have seven G’s left”). All the same, he claims not to worry much about money.

The poorest guy of the four is the 25-year-old in Chicago who’s making minimum wage and is single-parenting two children. Though he doesn’t have credit cards, he’s still underwater.

How much debt are you carrying now? I’m in a lot of debt. I have traffic tickets, hospital bills, old phone bills. I’m pretty sure that my debt from the tickets alone is roughly $3,000. By the time you get the money to pay the ticket, the fine has doubled. Then you get another one and can’t pay that one. Like, I’m on a boot [booted vehicles] list, and I got the money to get off the list, but my car got towed that morning, so I had to pay half that money to get it out of the impound. It just keeps going like that.

Unsurprisingly, his answer to how often he worries about money is “always.” Yet he also says he’s happy, a 7 or 8 on a scale of 10. Somedays, he says, he’s even a 10. That’s basically the same as everyone else: the others identify as 8s or 9s.

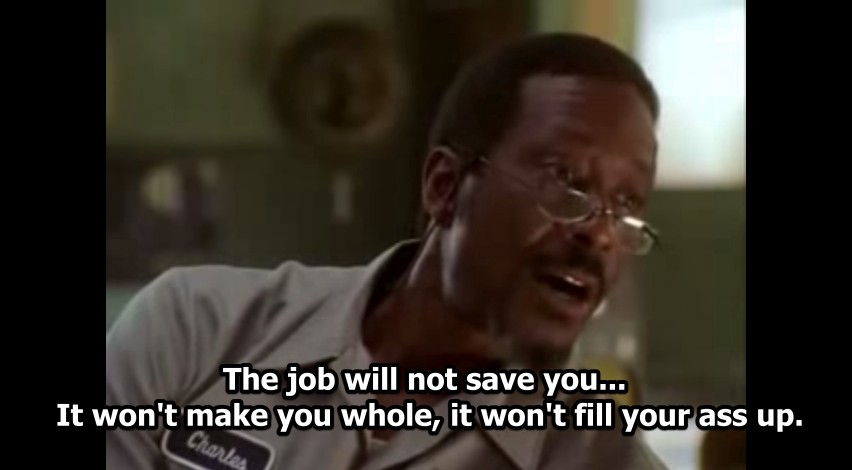

What struck me about these guys, on a macro level, is that our ideas of masculinity no longer preclude men from talking frankly about what they make and what they wish they made, their hopes and their challenges. None of these guys uses the word “impotence” the way Gabler does, but there’s still a frankness to their answers that I find pleasantly surprising.

On a micro level, these guys bear out the theory that no one is ever satisfied, no matter how much they have. Everyone wants more. When asked, “How much money do you think you’d need to have the life you want?” the guy getting paid poverty wages replies $50–60K. The middle-class guy making $50-$60K says he’s not greedy, so “my family and I could be very comfortable at $200 to $250K a year.” Meanwhile, the guy making $250K a year thinks $600K would get him the life he wants. And yes, even the millionaire CEO who says “there’s nothing that we need that we can’t afford” isn’t satisfied. His answer? $25 million.

Bear that in mind the next time you find yourself daydreaming about a raise. If you can’t find a way to be content now with whatever you’ve got, odds are that you won’t be content with more, either.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments