How to Buy a Used Car Without Getting Screwed: Part One

Buying a car can be painful. But there are lots of ways to tilt the playing field in your favor.

“Everything in life is somewhere else,” E.B. White wrote, “and you get there in a car.” But the process of buying that car can be pretty painful. Despite the rise of online research tools, car-selling startups, and Craigslist, most transactions still happen the old-fashioned way: at a dealership, face-to-face with a salesman. And in a recent Autotrader survey, less than 1 percent of respondents said they were satisfied with that experience.

Apart from financial services, it’s hard to think of any industry weighted against the customer as much as car sales. And since the average person will buy six cars in their lifetime, there’s a huge experience gap between the buyer and your typical car dealership, which sells about 1,500 cars every year.

Fortunately, there are lots of ways to tilt the playing field in your favor. I’m outlining one strategy below, which has worked for me several times. It’s meant for someone looking for a used car and who has decided on the category of vehicle (small crossover, family sedan, etc.) they want, but who otherwise doesn’t have a lot of knowledge or experience with either car sales or negotiations.

As a result, this strategy is inherently conservative, with an emphasis on avoiding risk and making well-informed decisions. But it also does not require an insider’s view into the world of cars, a strong mechanical background, or JFK-level bargaining skills to get a good outcome. After all, it’s better to avoid problems in the first place, rather than pay a lawyer to come in and fix them later.

Here’s how it works.

KNOW YOUR ENEMY

1. Car salespeople can say anything they want, because the law allows them to

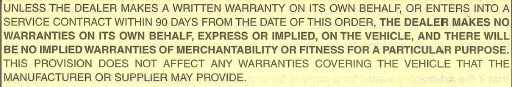

Almost every used car purchase agreement will contain three key blanket disclaimers:

- The dealership is not bound by anything the salesperson says.

- The car is not covered by the implied warranty of merchantability.

- The car is not covered by the implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose.

The first point simply means this: Not all car salespeople lie, but all of them are allowed to by law. The only thing you can take them to court for is if they lie about some specific fact that forms the basis of the deal you’re entering into — for example, if a salesperson says that you’re buying a 2015 Ford Fiesta with 5,000 miles, and it turns out to be a 2014 Ford Focus with 20,000 miles.

But anything else? Well, first of all, most car salespeople will stick to the kinds of subjective statements that don’t really mean anything. You won’t hear things like “the window seals are all completely intact and don’t leak” or “the fuel injectors are completely clean and working perfectly.” You will hear things like the car drives really well and the engine works great. In any case, even if they did say something specific and factual, the contract would disclaim it.

Now, this doesn’t mean that all salespeople are liars and crooks: I’ve met good ones and bad ones. The key difference is that the good ones don’t use all the leeway the law gives them, whereas the bad ones do.

But in general, it’s safest to assume that anything a car salesperson says is not true for any number of reasons. Some of them are benign: they haven’t spent a lot of time with that car, they haven’t reviewed its paperwork or service history. Some of them are not: they don’t want to disclose a defect, they are just outright making things up.

As for the warranties, the FTC has a good primer on what the two of them mean and why they might be disclaimed. Basically, unlike almost every other purchase of goods you will ever make, the dealership does not promise that the car they are selling you does what it’s supposed to do. Doubly so in the case of a specialized vehicle that you might expect to be able to, say, haul a trailer or race on a track.

So there could be significant structural or mechanical problems that they do not tell you about. After you drive off the lot, your car’s transmission could fall apart or you could have a catastrophic engine failure. In short, except for cases of outright fraud, you cannot hold a dealership responsible for any problems that come to your attention after you sign the purchase agreement.

Note that a few states provide extra protection for the buyer by preventing these kinds of disclaimers, although even that can be far from perfect. Your state should have a page on used car sales that will specify the rules— Google “[your state] attorney general used car” for more information.

But in general, assume that you are not protected from these standard disclaimers and proceed with caution.

2. Know what the definition of “as-is” is

To put the icing on this consumer-unfriendly cake, most used car sales are done “as-is.” Federal law requires that the dealership stick a piece of paper, known as the Buyer’s Guide , in the windshield of every car that they sell that tells you whether a sale is done as-is or under warranty.

The dealership is basically doubling down on their disclaimers about the implied warranties. By selling the car as-is, the dealership is telling you that once again, after you sign the purchase agreement you cannot hold the dealership liable for anything that happens with the car.

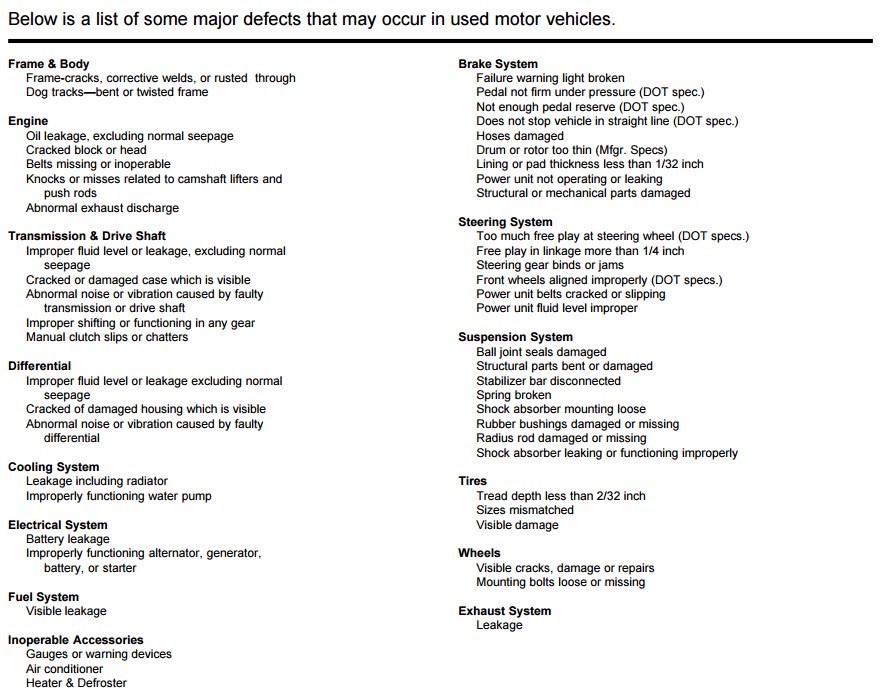

(Fun fact: just to drive home the point even more, the back of the Buyer’s Guide has a long list of things that could possibly go wrong that would not be covered under an as-is transaction.)

As with the warranty disclaimers, some states prevent as-is sales outright. For example, New York state does not allow as-is sales, but Texas (where I live) allows them.

In general, you can think of it this way: the warranty disclaimers protect the dealership from anything that happens before you take possession of the car, and the “as-is” sale protects them from anything that happens after you take possession.

Guess who isn’t protected during any of this?

3. You can’t trust CarFax and AutoCheck on a lot of things

Most dealerships will provide you with a CarFax, AutoCheck, or similar report for free when you shop. And although those reports can be good, they are by no means perfect, as documented by Consumer Affairs and ABC News. On the one hand, some cars with clean reports will have had accident damage, salvage titles, or odometer fraud. On the other hand, cars that are perfectly fine may have been incorrectly flagged by one of these agencies for reasons as simple as a typo or a misaligned spreadsheet column.

All of these reports are data aggregators. They purchase vehicle reports from multiple sources, including dealerships, insurance companies, service stations, and state DMVs, and combine them into one simple readout. However, they are only as good as the data that gets reported in the first place. If someone gets in an accident and doesn’t report it to their insurance or get it repaired at a body shop, the report won’t show anything. Likewise, if someone does all their oil changes and basic maintenance at home, they won’t get the “oil change” badge on CarFax.

In addition, these agencies don’t always give you the complete context around certain types of transactions. For example, CarFax will tell you not to worry about cars sold at auction by their manufacturers — even though these cars are almost exclusively bought-back lemons.

Obviously, you can feel confident avoiding a car with multiple red flags in a report. It’s the clean ones that you should still worry about.

Luckily, there are two ways to check that a car is as good as its CarFax says. The first is a mechanical inspection — this should detect big issues such as odometer fraud, frame damage, and signs of extensive repair (more on this later). The second is to physically look at the title and any other associated paperwork before you purchase it, and check for the following:

- VIN on the title matches VIN on the car

- Title isn’t branded (junk, salvage, flood damage, etc.)

- The car has never been bought back by its manufacturer

- The car has never been owned by an insurance company

You can also check for things that might not be deal-breakers, but may indicate that the car isn’t as valuable as the dealer wants you to believe. These might include unusually high odometer usage by one owner, or the car being owned by a leasing or rental company before.

4. Car pricing is more irrational than you might think

When it comes to pricing, dealerships are completely opaque. You have no idea how they arrive at the selling price of the car, or (most importantly) how much room they have to negotiate.

Then, there’s the private market, where, sellers base their prices off of a complex formula that includes what they see on Autotrader, when their next loan payment is due, how they’re feeling that day, how much they’re hiding about the car, and how bad their spelling is relative to their competition on Craigslist.

And finally, there’s the third-party “information” sites that offer “fair market value” estimates, such as KBB.com or Edmunds. However, if you read the fine print, you’ll find that the “fair market value” that they give you defines “fairness” as the delta between the asking price of the car you want to buy, and the average selling price of similar cars over the past few months from the dealership network. It does not take into account whether that sale generates $5 or $5,000 in profit, i.e., whether you are getting gouged by the dealership or not.

Consider that the average profit on a used car sale was over $2,300 in 2014, and decide for yourself how fair that market value really is.

At this point, one thing should be clear: the car buying process is structured, with the full blessing of the law, to keep potentially vital information away from the consumer at every stage of the process. The good news is that now you know that the information gap exists, you can take steps to close it.

BE PREPARED AND BE CRITICAL

5. Pay a certified, independent mechanic to inspect your car before you buy

Maybe you’ve been a gearhead since you were old enough to hold a wrench. Maybe you have an ASE certification. If so, that’s great — you can do your own inspection and move on.

For the rest of us, I would encourage you to pay a certified, well-reviewed, independent mechanic to inspect your car after you’re ready to make an offer but before you buy it. This should take a couple of hours and may cost a hundred dollars or more; my mechanic charges $125. During the inspection, the shop should put the car on a hydraulic lift and check it thoroughly for everything from leaks to odometer fraud to tire, belt, and brake wear, as well as reading the on-board diagnostics.

Why spend the money and go through the trouble? Well, first, you have to make the most of your limited pre-purchase time with the car. Most test drives last 15 or 20 minutes, although you may get the car for up to a day on your test drive, which is great! Even then, you’re probably focusing on other things throughout: how does the car handle, do I like the color, can I fit my groceries in the trunk, etc. There are so many things to think about that you may not have the capacity to also do a thorough inspection of the car, even if you are totally qualified on paper to do it.

Second, the dealership has no obligation to tell you the whole truth about your car — if they even know it! Your mechanic, on the other hand, can not only keep you from buying a bad car in the first place, but can also give you quite a bit of leverage to negotiate extras or “nice-to-haves” if there are quick repairs that need to be made.

And if a dealership doesn’t let you inspect the car before you buy? My advice would be to walk away, unless you are mentally prepared for that car to blow up as soon as you sign the paperwork.

6. Use trade-in estimates and auto auction prices as a price benchmark

Dealerships get most of their used car supply from auctions and trade-ins. They then spend some amount of money on reconditioning the car — although this might be less than you expect, since they pay lower than retail prices for parts and service, especially if they have a shop on-site. Finally, they add a markup, which is a catch-all amount that should cover their operating costs such as rent, utilities, dealership debt, salaries, etc., plus whatever profit they intend to make.

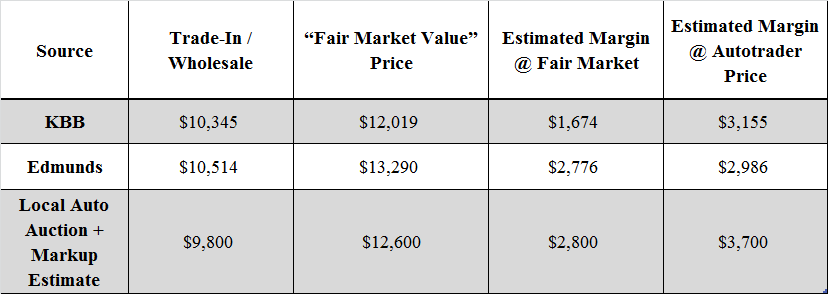

Fortunately, you can get a pretty good estimate of what a dealership paid for similar cars. First, look at the trade-in estimator of sites like KBB or Edmunds, which will give you an average of recent trade-in prices for cars like the one you’re looking at. You can then compare to their estimated “fair market value” to get a sense for how much that car has been marked up.

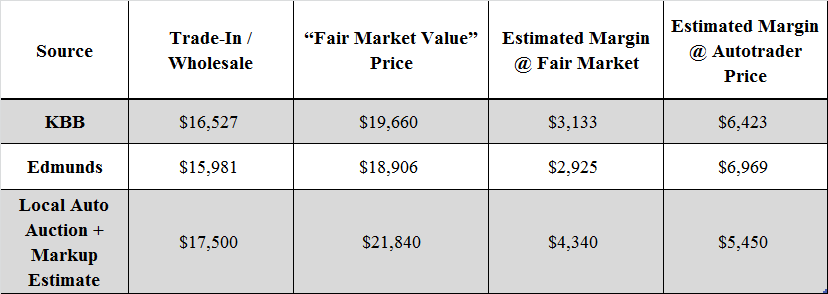

Second, search for local auto auction market reports (Google your city, county, or state and “auto auction”). With any luck, these auto auction sites will have publicly available lists of every vehicle sold at auction by make, model, year, mileage, and (in some cases) vehicle condition, and you get to see actual, individual transactions rather than some calculated average. Here are two examples from my area.

These market reports tend to be more current and more geographically-specific than the third-party guides, which look only at the level of multi-state regional markets [PDF]. For instance, the guides would tell you that trucks rule the road in the “Southwestern” market, which includes Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana. But by looking at local market reports, you’d also be able to see demand trends. When I was shopping for my car, I learned that performance cars (especially European ones) commanded higher prices and sold faster in Dallas vs. the rest of the Southwestern market, full-size SUVs are big in West Texas, and in Austin it’s hybrids and Japanese cars.

Once you have this auction price, assume that the dealership spends about $500–700 in reconditioning spend, plus a 20 percent markup for various costs, plus profit. This will give you an idea of the real “fair market price” for the car. From there, you can compare with the actual AutoTrader prices to see how much the dealership is probably making from the sale.

A couple of real-world examples:

For a 2010 Honda Accord EX sedan with 50,000 miles, the average AutoTrader list price in my area was $13,500.

So, by my estimate, dealerships had up to $3,700 of margin to work with at the Autotrader price, and in general were still making $2,000 or so at the average transaction price.

For a 2013 Chevrolet Camaro LT coupe with 30,000 miles, the average Autotrader price was $22,950.

Right away you can see that the average margins are higher than our Accord example, and there’s also a bigger discrepancy between the KBB/Edmunds estimates and the local auto auction. As any Dallas resident can probably tell you, Camaros are in high demand around here (especially orange and green ones). I would expect that that number is higher relative to the rest of the “Southwestern” market, which includes the entire rest of Texas, as well as Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana. That’s probably why local dealerships feel more comfortable charging $3,000 more than the “fair” value elsewhere.

In any case, one thing should be clear about the car buying process: research is key. Armed with a mechanical inspection and some detailed information about prices, you should feel much more confident about making a good purchase — or at the very least, avoiding a bad one.

Next in Part II: Going from “good data” to “good deal.”

How to Buy a Used Car Without Getting Screwed: Part Two – The Billfold

Darryl Campbell is a former medieval archaeologist and Jeopardy! contestant. He lives in Dallas, and tweets at @djcampb.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments