Life, And Doing Money, In The New Middle Age

We talk a lot about how we do money as relatively young people at this site and we talk about how we expect to do money once / if we retire. What with one thing and another — the final season of “Mad Men;” the opening of the new Noah Baumbach movie While We’re Young, which was covered on both the Culture Gabfest and Filmspotting — I’ve also been thinking a lot about middle age lately. Turns out I’m not the only one.

Researchers say that old age should be defined as having 15 or fewer years left to live, which for the baby boomers means that they are still middle aged until their 74th year.

“If you don’t consider people old just because they reached age 65 but instead take into account how long they have left to live, then the faster the increase in life expectancy, the less aging is actually going on,” said Sergei Scherbov, World Population Program Deputy Director, at IIASA.

“Older people in the future will have many characteristics exhibited by younger people today.

“What we think of as old has changed over time, and it will need to continue changing in the future as people live longer, healthier lives. 200 years ago, a 60-year-old would be a very old person. Someone who is 60 years old today, I would argue is middle aged.”

It’s easy enough to fantasize about being a spry 70, puttering around gardens, playing with grandchildren, binge-reading novels, maybe solving mysteries in our spare time. It never occurred to me that what I was picturing was life in the new middle age.

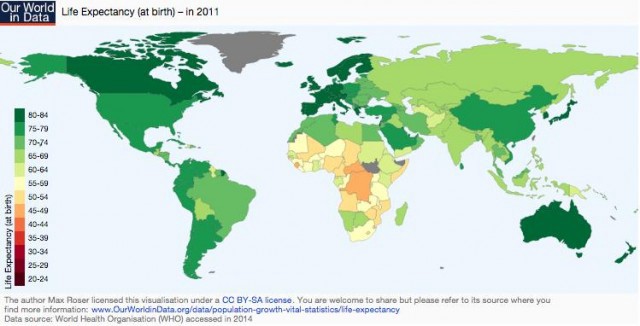

Life expectancy still varies considerably worldwide:

Though not as drastically as it did in the 1950s. Life expectancy in the US and Canada was 68 years at birth then; now a baby in the US has a slightly less rosy outlook (79 years) than does a baby in Canada, Australia, Israel, Japan, or Western Europe (80–84 years, and attributable no doubt in part to the glory of socialized medicine).

That said, I’ve been told numerous times that “life expectancy” as a measurement is a flawed way of looking at the data, and not merely because it can differ so much from individual to individual even within a country: a white woman in our nation’s capital has a much better chance of making it to 85 — or indeed, like my Grandma Edna, to 102 and counting — than an African-American male from Washington, DC.

It’s also an imperfect lens with which to view the past. Childbirth used to be tremendously dangerous both for women and for infants. (Even with modern technology, it can still be pretty damn dangerous.) So many women died in or after labor in the pre-penicillin and pre-C-section days that having a step-mother in a family was relatively common. Hence the prevalence of evil step-mothers in fairy tales.

If you did survive young childhood 200 or even 100 years ago, though, you would find that your potential lifespan was not that different from what it is now. Assuming you didn’t step on a rusty nail or get caught up in a war, anyway. LiveScience explains:

the inclusion of infant mortality rates in calculating life expectancy creates the mistaken impression that earlier generations died at a young age; Americans were not dying en masse at the age of 46 in 1907. The fact is that the maximum human lifespan — a concept often confused with “life expectancy” — has remained more or less the same for thousands of years. The idea that our ancestors routinely died young (say, at age 40) has no basis in scientific fact. …

When Socrates died at the age of 70 around 399 B.C., he did not die of old age but instead by execution. It is ironic that ancient Greeks lived into their 70s and older, while more than 2,000 years later modern Americans aren’t living much longer.

That means that the crux of the argument above — “200 years ago, a 60-year-old would be a very old person” — becomes a bit suspect. Nonetheless, let’s go with it and re-label folks middle-aged until they hit 75.

That means:

+ If you are faithful to averages and die at 79, you’ll only have to be “old” for four years!

+ If you plan well for the future, you may end up retiring in middle age. The shift might be semantic, but it could still have a demonstrable effect on how you feel and act.

+ Maybe, if you keep thinking of yourself as middle-aged instead of old, you’ll be able to stay in the workforce longer and so prep better for retirement. My mom, for example, is only retiring next year, when she hits 70. I’ve never asked her whether she feels old because it seems like a ridiculous question. She identifies as “Mimi” rather than “Grandma”; she is proficient on a Mac as well as in the weight room in her gym; she dances, she goes on photography trips, she watches shows on Netflix …. She just hiked Mount Everest, for god’s sake. There’s nothing “old” about her.

But:

+ What if this is part of our grand cultural delusion that we’ll never get old, and that affects how we save or don’t save for retirement?

+ When does “youth” officially end and midlife start?

+ Is being “old” really that bad? Like I said, I’ve considered dreamily what it might be like to be “old,” whereas I’ve never given a moment’s consideration to my future as someone middle-aged. There’s romance in youth and there’s wisdom in age; what is there in midlife, besides crisis?

I’m really asking. If we’re going to be in midlife forever, it would be helpful to have something about it to look forward to.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments