Can’t Take it With You #2: Colin Dickey, Writer and Morbid Anatomist

by Rachael Maddux

We’ve been dying for a very long time, but so much of what we take for granted about death — what we desire and value and fear about the end of life — hasn’t always been the going concern. The basic mechanics remain the same, but that’s about it. So what can be learned from looking at how we — as a culture, as a glob of cultures — have handled the concerns of death, historically?

Colin Dickey is a writer and teacher whose work has taken a probing long-view of death and dying — in particular, what happens to the body post-mortem. His 2006 book, Cranioklepty: Grave Robbing and the Search for Genius, explored the penchant of certain 18th and 19th century folks for exhuming and stealing body parts of famous men (Haydn! Beethoven!) and, more broadly, the shadow economy of grave-robbing that stemmed from clashing priorities of religion and science. Death has remained a focus of Dickey’s work; I especially like what he’s written about hauntedness — of hotels, of foreclosed houses.

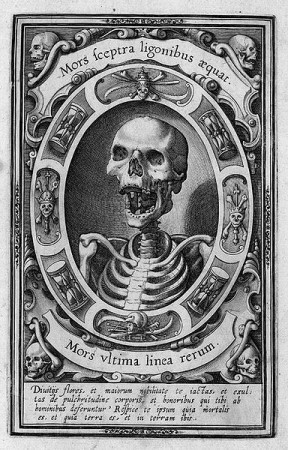

Dickey is also the managing director of the Morbid Anatomy Museum, opening next month in Brooklyn. Morbid Anatomy is the spooky brainchild of artist Joanna Ebenstein, who in 2007 started a blog that eventually expanded into a tiny dark empire of traveling exhibits, a lecture series, and a small library in Brooklyn, N.Y. Ebenstein’s collections of curiosities and ephemera explore the historic relationship between death and medicine and art and culture, but the museum won’t just be a place to oogle weird stuff — it’ll be an open, curious space in which death will be thought about and talked about and grappled with and marveled at, and we don’t have enough of those.

Ebenstein and Dickey have also co-edited The Morbid Anatomy Anthology, out last week, a fantastically illustrated collection of essays based on lectures given at Morbid Anatomy events over the years. A sampling from the table of contents: “Ghost Images: The Curious Afterlife of Postmortem Photographs,” “Demonic Children & Their Curious Absence in the European Witch Trials,” “Hell Époque: Death-Themed Cabarets & Other Macabre Entertainments of Nineteenth Century Paris.” It’s the first publication from the museum’s in-house press.

I talked with Dickey in early April, just before Tax Day, when he was fresh off a meeting with his accountant. I had a feeling he would have some smart things to say about death and money, and I was right.

A couple notes, before we get into it: Towards the end of our conversation, Dickey and I got into the changing historical feelings about leaving your body to science, which hopefully one of the next installments of Can’t Take It With You will explore in more depth. Also, while the Morbid Anatomy Museum is mostly funded, there’s a Kickstarter campaign underway to carry it across the finish line. If it strikes your weird fancy, throw in a few bucks — this place is going to be really neat.

So, how are your taxes?

They are OK. They are complicated, but you know, taxes are taxes.

Looking through a lot of the stuff that you’ve written, death isn’t an explicit theme, necessarily, but it is kind of a thread through a lot of it. How do you explain that? Is this something that you recognize as an interest that’s been ongoing in your life?

Yeah, actually. My first book was on famous peoples’ heads that were stolen out of the grave in the 19th century and, I guess you could say, the economics that grew up around the body generally and also specifically the skulls of quote-unquote “great men” and notorious men and women. How that came to be my first book was sort of an accident, but then I became somewhat of a go-to person about death. But I think that I have remained consistently interested in the changing and evolving attitudes of how we both treat the dead body and how we approach morning, which are two things that we tend to think of as static, in the way that death is static — that it happens to everybody and therefore mourning and ritual are probably unchanging. But, in fact, they are sort of constantly in flux and changing generation by generation. So that’s what remains fascinating to me and what I try to do in some — not all, but some — of the writing that I do.

I know you guys are trying to raise money for the museum — how do you pitch it to people? What’s the hook for someone who’s like, “I’ve got 20 bucks I might give you for this weird thing”?

It’s really a one of a kind place that will be a place that is a serious interrogation of a lot of these questions — the intersection between medicine and religion, between death and art, between spectacle and culture. Something that both seriously approaches these things but is not necessarily an academic or overly scholarly. It’s a way of approaching these questions through what Joanna likes to call “rogue scholarship” — a way of inviting people to participate in these questions and ask about their own relationship to the body, to the history of medicine, to death and dying, and those sorts of things. It has parallels a little bit with the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia, a little bit with the Museum of Jurassic Technology in L.A., though it will be significantly different from both of those. It will really be a museum that New York currently doesn’t have. New York doesn’t have a straight-up medical museum of any kind, and this will help fill that niche, while at the same time it will be its own idea and its own concept unto itself.

I feel like there’s a lot of interest being paid to death and death rituals and death culture and also kind of the more “old timey death stuff” — if that’s fair — online, now. There are people who I follow on Twitter who are like, “Here’s this baby in a jar! Here’s this jewel-encrusted skeleton!” I wonder if this interest in that stuff is almost a reaction to the way that death is so sanitized now. Does that seem like a fair way of explaining it?

My working hypothesis is basically that maybe not every generation but every other generation, our mourning rituals and our burial rituals change pretty dramatically. You know, cremation — which you and I now think of as pretty commonplace and no big deal — was not even allowed by the Catholic church until 1957. It wasn’t employed widespread until the first half of the 20th century. The technique wasn’t perfected until about 1870, in the modern form that it is now. That’s a pretty short time to go from something being technologically unfeasible to a sin to now a commonplace idea. Most people of a certain age and demographic will tell you that they plan to be cremated, whereas their parents wanted the “embalmed, perfect-looking corpse, thousands of dollars on a coffin” kind of funeral. And I think now that’s changing once again, with the move towards green burial.

I think that every so often we reimagine what it means to mourn and what it means to bury somebody, and I think that we’re going through that time right now. So the people who are circulating those photos, I think they’re very fascinated and really intrigued — and some of them, by no means all of them, but some of them I think don’t yet have a language for that intrigue. It’s more than just “these are morbid kids,” it’s more than goth culture. I think it really is a curiosity about the way the Victorians dealt with death, the way that medieval Christians dealt with death: How are these things different and is there any sort of value and interest for us now in the way that other cultures approach death and dying? I think one of the main things we want to do with this museum is provide a forum for those kinds of questions. We’ve had, for years, speakers along those lines, but that’s something we hope to continue to do on a larger scale.

Working this closely with and thinking about death and attendant subjects in a more historical context — does it change the way that you think about it in your own life? With people that you’re close to, or even your own sense of mortality? Do you have to toggle back and forth between, “here’s Victorian death culture” and “here’s immediate life situations”?

On the one hand, I have this very abstract intellectual interest in death. You know, “I think that it’s ridiculous to spend thousands of dollars on a funeral when you could just bury somebody in a burlap sack in the backyard and that could be just as meaningful!” I’ll occasionally get on a high-horse about something like that. And then something will happen, a friend of a friend will die, and it will become very real and it will suddenly change the stakes. What I have come to learn and take away from it is, the way that we all handle death is really stubbornly personal. I try my best to be sympathetic to that and respectful of that and to see that as part of the human condition, the variety of mourning [rituals]. So despite what one can concoct intellectually, I think it remains a personal relationship that you have with your own mortality and with the people around you.

The subjects of death and money strike me as similar in that it’s a thing that everyone has to deal with. It’s literally impossible to not deal with death, but money — I guess you could be some kind of grifter outdoorsman and exempt yourself from capitalism. But mostly it’s a thing that everyone has to deal with, but it’s so tricky to talk about it.

Yeah, and for me that connection is also in the sense that both are inherently social activities. Whether or not one can sort of live outside of money, what money represents is a series of very complicated and fluctuating interdependencies between people: the relationship you have with your boss, the relationship you have with your partner, the relationship you have with your friends that you’re buying drinks for, the small shop down the street where you buy your groceries. It’s this network of relationships and money is just sort of the symbol of that transaction. And I think of death as being sort of similar. It’s possible to die alone, and I know that some people do, but for the most part what happens when somebody dies is those interconnected relationships are suddenly upended and part of the web is suddenly cut out and we all have to sort of rethink how we’re going to reconnect those strands: “What do you do about that person’s family?” And, “What do you do about that person’s business?” And, “What do you do about that person’s dog?” It becomes the other side of that coin of which maybe money is the other side.

You mentioned earlier about the economy that came up around body-stealing that you wrote about in your first book. Is, uh, this still an issue?

The reason it was an economic issue was because it was also a religious issue. Prior to, like, 1820 to 1840, you could not in any way molest a dead body lest you imperil that person’s soul for the resurrection. I’m speaking almost entirely in terms of Christian Europe and America — the body needed to remain undisturbed for the second coming. So this presented a huge problem for medical schools who needed cadavers to dissect, because they could only dissect executed criminals. Those were the only people it was thought had forfeited their souls and thus could be, like, doubly executed — their bodies were killed, and then their souls were annihilated via dissection. So almost immediately it becomes a supply and demand problem. That’s what happens from about 1780 to about 1840: The medical schools put huge pressure on the need for cadavers, and that’s where you get a lot of grave-robbing and a lot of body-stealing, and you get unscrupulous people basically stealing from cemeteries — stealing from prison cemeteries and insane asylum cemeteries — and delivering no-questions-asked bodies to medical schools. They were paid well.

In extreme cases, you get Burke and Hare, who were the Scottish guys who started murdering people to sell to anatomy schools because there was good money in it. Finally what had to change is, you had to change a whole cultural attitude about what it means to die and what it means to leave your body to science. That’s why you have people like Jeremy Bentham, who had his body stuffed and put on display in University College London. One of the main reasons he did that was to show everybody it was OK to leave your body to science and that if you were a progressive, positivist thinker, this was what you wanted to do — you wanted to leave your body to be useful and not just rot in the ground waiting for Jesus. And so that was a real cultural shift. That’s sort of how those economics came and went. You’re right, it doesn’t happen really anymore.

That’s good.

I know, right?

Have an idea for a future installment of Can’t Take It With You? I’d love to hear from you, especially if your life or work touches on the intersection of death and money in some unexpected way. Please get in touch.

Rachael Maddux is a writer and editor living in Decatur, Ga.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments