“Welcome to the paradise of the modern artist.”

“Welcome to the paradise of the modern artist.” — An Interview With Tom Toro, ‘New Yorker’ Cartoonist

by Megan Reynolds

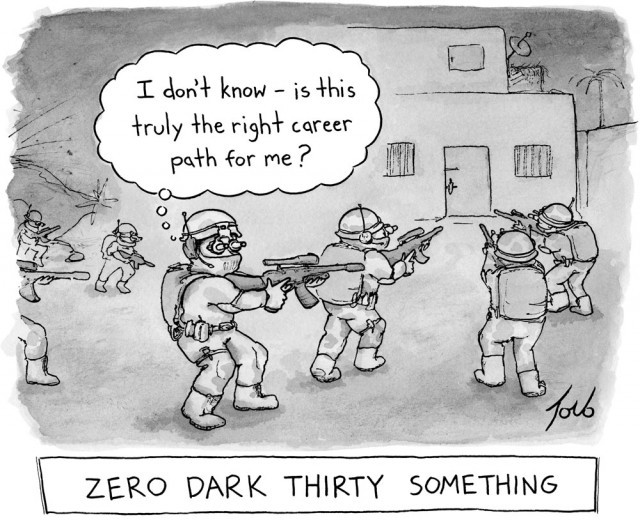

I met Tom in English class during my sophomore year of high school, and we became acquaintances and occasional friends. Mostly, I had a crush on him. After high school, I moved out of the Bay Area and to the East Coast, where I received sporadic updates on high school friends from my good friend Julia. She mentioned something about Tom drawing for the New Yorker, a piece of information I filed away until I saw this cartoon posted on Facebook. I recognized the signature, got his email from Julia, and had a nice email chat with him about cartooning, the pursuit of creativity and our generation’s inflated sense of self-worth. Here is our conversation, edited a tiny bit for length.

Tom! Tell me how you ended up in this job.

“Job”? Cartooning isn’t a job — it’s a passion, a calling, a raison d’etre! Also, there isn’t a salary or benefits — so there’s that distinction as well. I was in my mid-twenties, living at home, swamped in student loan debt (hilarious, right?), and so I did what any rational person facing that situation would do. I started drawing cartoons. It didn’t come out of nowhere; I’d drawn a weekly strip for my college newspaper, which had a grand total of three or four fans (depending on my number of roommates at the time), and as a kid I’d always been enamored with The Far Side and Calvin and Hobbes. To this day if you showed me a Gary Larson panel I could probably quote the caption verbatim. But I never considered going into cartooning professionally — who does that? It was always more or less a fun pastime, something vaguely on the periphery of my artistic ambitions.

I greatly feared in the very depths of my soul, that I was an artist. But what kind of artist? In this era when it’s possible to read every novel ever published, watch every film ever made, listen to music from across the globe, all at our fingertips, how can a person with creative inclinations decide where to channel their energy? No, I’m serious — how? Tell me! We live in the Age of Influence, but to what end? Also, I was raised with a grossly disproportionate sense of self-worth, which I prefer to see as a generational symptom rather than my own psychosis.

Flash forward a handful of years and there I am with an impressive heap of accolades and diplomas — and its long shadow of student loans — without a clue about what to do with myself other than read Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain religiously. One weekday afternoon I’m lying in my childhood bedroom when I happen to pick up a copy of The New Yorker. Seeing the cartoons inside I remember thinking, “Wait a minute… this looks familiar. This is something I can do. Why not?”

Did you think this is what you would end up doing?

Golly, no. I’ll tell you what, though — I really wanted to be a Disney animator! I adore those old hand-drawn movies. My god, can you imagine? Each frame inked and painted by hand. Twenty-four frames per second, with multiple planes of action. It’s unbelievable. Pinnochio is no lesser a work of art than the Sistine Chapel. When I was little, I used to pause my VHS copy of The Lion King or The Little Mermaid and try to copy the freeze-frame down on paper, which was difficult since the image jittered and the tape would automatically replay after a few minutes. Nothing artful ever came from my efforts but I did feel satisfied in paying penance to the masters of the craft. Lucky for me I chickened out and never pursued animation seriously, because look what happened. Pixar has taken over. What they can do in the computer realm is absolutely jaw-dropping, don’t get me wrong. But when it comes to pure artisanship nothing holds a candle to the Disney classics.

Let’s talk money. How much does a cartoon go for?

What, the winter hasn’t depressed you enough, now you want to talk to a cartoonist about money? Bust out the Kleenex. In all seriousness, though, The New Yorker prefers that we don’t disclose how much a cartoon sells for. I don’t really know why. I’m assuming it has something to do with behaving gentlemanly. What I can say is this: I read an interview with Roz Chast somewhere online (i.e. I could be lying to you) where she mentioned that at the time she began publishing in The New Yorker, in the late 1970’s, selling one cartoon a month was enough to pay her rent. Unfortunately that isn’t the case any longer — not even close — unless you share an apartment with two or three other New Yorker cartoonists and everyone pools their earnings.

The publishing industry isn’t immune from the wage stagnation that has occurred in America over the last several decades; in fact, it’s been hit especially hard with the advent of digital media. I just feel lucky that a place like The New Yorker still exists so that I get to see my cartoons in print — extraordinarily lucky! I don’t want to sound ungrateful. Cartooning for the New Yorker is a dream come true. It’s a rare, rare thing. There are more presidents of countries, there are more Oscar winners, there are more astronauts than New Yorker cartoonists. I feel unbelievably blessed to be among the chosen few. (Inasmuch as an atheist can feel blessed). But that doesn’t change the simple math that the cost of living has skyrocketed while wages have flatlined. Every cartoonist I know has a second career doing something else, or is married to a lawyer. How I make ends meet is I work part-time customer service jobs, and if that’s not enough I shamelessly mooch off my parents. I’m almost thirty-two years old. Welcome to the paradise of the modern artist.

What’s your process like for a cartoon, from start to finish?

My process has evolved over the years. By which I mean, my early cartoons were subhuman dreck and I’ve only recently learned how to walk on two feet. In the beginning I would spend a ton of time with the artwork, hours and hours on each drawing, because I was obsessed with developing a trademark style. Naturally, the result was terrible. As a wannabe cartoonist, you flip through The New Yorker and the first thing that jumps out at you is how unique each artist looks. You think, “Ah ha! From this I deduce that I, too, must be flagrantly unique!” But the trap of concentrating too much on visual style — other than your work becoming preening and self-aware — is that you ignore the writing. The joke itself falls by the wayside. It’s all about capturing that joke, hitting upon that workable idea somehow. Remember: We’re in the business of gag cartooning. Emphasis on “gag.” Humor is paramount. A good joke can be drawn sloppily, but a bad joke can’t be rescued with a fancy drawing. Only when I flipped my ratio of drawing to writing — spending a hundred times more effort developing the gag and a hundred times less effort obsessing over the style — did I begin to find success. The New Yorker finally bought the 610th cartoon that I submitted to them. And believe it or not, that’s lightning quick! It took David Sipress twenty-five years to break in, I think. William Haefeli got in after nineteen years. Like I said before: It’s a rare, rare thing.

Each week I’ll try to come up with 10–15 new ideas. I’ll lay on my bed after reading the morning newspaper and eating a hearty breakfast of oatmeal (hot) and yogurt (plain), and I’ll just start brainstorming. For some reason I need to be supine. I don’t know why. Perhaps the imminent threat of a nap is what sharpens my wits. It can take several hours for the first idea to click, during which time I will question the point of my existence on Earth. Why am I not battling global warming? Why am I not healing the sick? Painful are those first fallow hours. I desperately want to quit, I don’t see the point, I hate everything. And just when it seems like all hope is lost — bloop. Something will occur to me. Or not. Or I’ll go on squirming futilely. I’ve become convinced that this is precisely what separates a professional cartoonist from an amateur: endurance. The ability to simply sit and suffer until something happens. While knowing all along — beware! — that even should an idea manifest, even an extremely good idea, it has a pathetically small chance of selling.

The editor Bob Mankoff says that he reviews 1,000 submissions each week and buys roughly 20 of them. However, that should be the last thing on your mind while brainstorming. Like death — it happens to the best of us, so why worry? Once I’ve filled my weekly quota, I’ll sketch up the ideas. I use Micron 0.5 pen on regular printer paper. (I submit roughs because The New Yorker is comfortable with my work by now, thank Jove! In the beginning all of my submissions had to be full-blown cartoons, ink, watercolor, the whole shebang.) I primp the sketches in Photoshop, slap on a caption, compile them into a PDF and hit “send.” Then when an idea magically sells — once, maybe twice a month, although I’ve gone on half-year droughts without selling — I’ll toss the sketch on a light board and draft a nicer drawing on Bristol paper, ink it, add wash, scan it, do touch-ups in Photoshop. Most cartoonist don’t scan their own work; they give the finish to The New Yorker for processing. But I’m anal and I need the final say in every little detail. It’s outrageously time-consuming. I owe my sanity to Ira Glass and This American Life’s online radio archive. Occasionally a note will come back about something they want tweaked in a drawing, which is annoying, although invariably they’re correct. Once I was asked to fix an image that was deemed “too vaginal.”

How solitary is this as an occupation? Do you ever collaborate with other people?

Cartooning is about as solitary an occupation as it gets. I’ve been doing this for about six years now, and I’ve only met the editor, Bob Mankoff, twice. We’ve talked on the phone once. The routine is, I send him my weekly submissions by e-mail and he responds with an “ok” if I sell one. And, uh… that’s about does it for our communication. Very manly, I think. Every so often I’ll come up with an excuse to pester Bob with questions, when I’m feeling lonely or ignored. Or I’ll suffer an unexpected gush of humanitarian goodwill and brotherly feeling and send him what amounts to a platonic love letter — which he rightly disregards. But those are deviations from the norm, which is isolation. I believe it’s somewhat different for New Yorker cartoonists who actually live in New York City (weird) because they can submit in person and rub elbows at the office if they so choose. This gives rise to something called “camaraderie.” Me, I use remoteness to hone the ironic detachment of my humor.

Is there a next step for you beyond the New Yorker?

An obit in the Times, perhaps? This is pretty much the plateau. There’s no better venue than The New Yorker. It’s the acme of cartooning.

Is this a secure gig? Is it something that feels solid, or are you on the lookout for other stuff, just in case?

I’m always on the prowl for mistresses, creatively-speaking. A popular side gig among cartoonists is comedy writing, for film or television. I also write scripts, short stories, novels, none of which are making me any money at the moment, but hopefully over time things will pick up.

You mention that you feared in the depths of your soul that you were an artist, which is a fear that is valid and shared by many. How do you think this will influence your “career path” from here on out, if your stint as a daily cartoonist has ended? Are you going to look for other, I don’t know, steady drawing gigs? What’s your plan?

The Daily Cartoon for The New Yorker’s website is a fairly new enterprise they’re testing out, and it only supports one artist at a time, so that can’t really factor into my career outlook financially or otherwise. It offers great visibility and it’s fun while it lasts, but The Daily Cartoon is also somewhat of an awkward fit. I’ve trained myself to come up with cartoons on a weekly basis. By necessity that means taking a more timeless, less topical approach. Rarely do cartoons in the magazine address specific events in the news. Or if so, it’s done from an oblique perspective that we as readers understand relates to whatever crisis/scandal/market crash has recently occurred, but which is actually a spoof on crises/scandals/market crashes in general. As a cartoonist you always want to aim for longevity. The longer your stuff sticks around the more royalties you can accumulate. A major bonus of cartooning for The New Yorker is that upon publication your work goes into “the cartoon bank,” where people can buy prints of it, or license it, or get a Jell-O mold made from it. I see a percentage of those sales every month — with a microscope! But seriously, it’s great. I can only assume that over the years royalties become a pretty substantial portion of cartoonists’ income.

If there’s no next step for you beyond the New Yorker, with the New Yorker being the apex of contemporary professional cartoons, will you turn to the wiles of the internet?

I’m a Luddite, sort of. I don’t believe there are technological solutions to what ails humanity. That’s like saying, “Hm… the leeches aren’t curing your fever, so we’re going to add more leeches.” The solutions are in the exact opposite direction: dialing back, unplugging, slowing down, letting go of the myth of control. (Yikes, I just ruined whatever chance I might have had of holding political office.) Which is a preachy way of saying: I don’t have much interest in posting cartoons online. As far as I can tell, the Internet is a massive society of hobbyists. Fascinating, certainly, but nobody’s making any money from what they do. I’m not on Facebook or Twitter, I don’t traffic in the currency of “likes” or “tweets” because they don’t hold any real value. If some online business model arises in which talented people get paid for what they create, I’ll be the first to send in my resume. But for now, no. I have plenty of other ways to fritter away my time on Earth. (Your guys’ website is excluded from everything I just said.)

Also, what do you think about dudes like The Oatmeal? He’s made a lot of money off his personal “brand”, but it seems relatively banal. Is this a path you want to go down?

What the f* is The Oatmeal?

Megan Reynolds lives in New York.

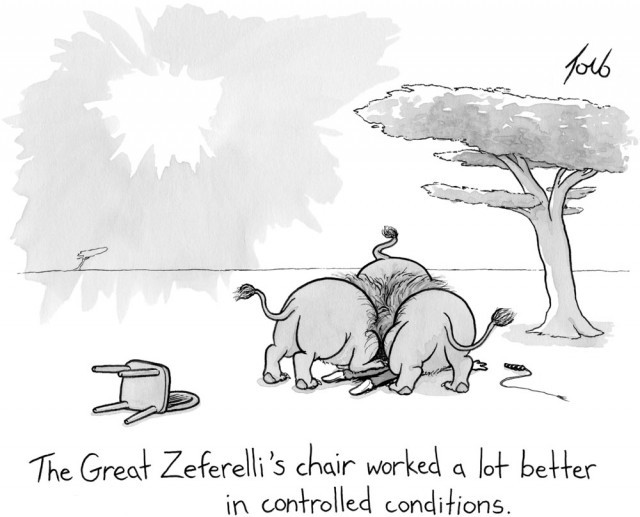

Illustrations by Tom Toro.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments