The Most Memorable Rideshare Trip I’ve Ever Taken

by David Raether

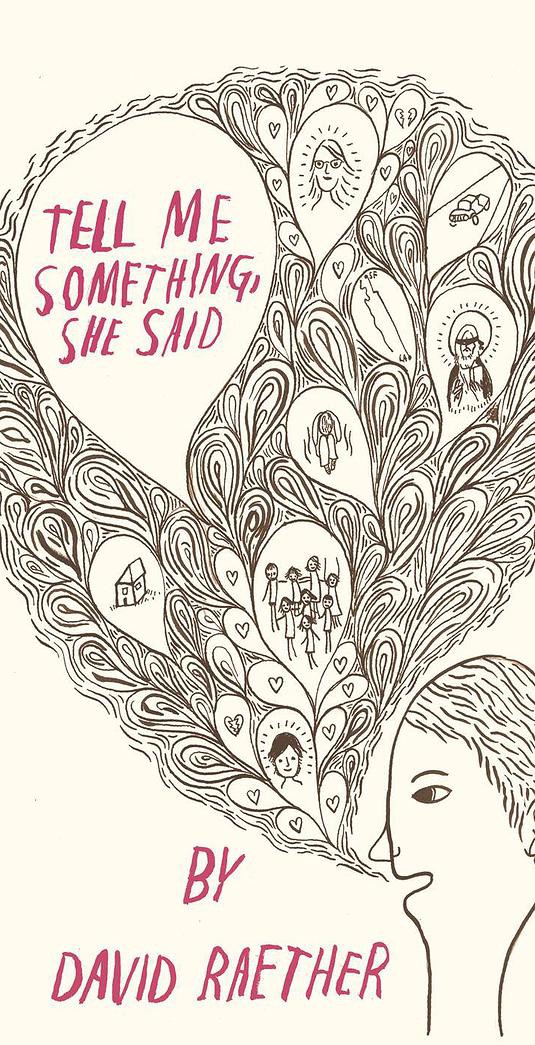

The following is an excerpt from David Raether’s new memoir, Tell Me Something, She Said, which is about Raether’s experience falling in love, becoming a sitcom writer in Los Angeles, losing everything, becoming homeless, and rebuilding his life. Raether often used Rideshare to travel from Los Angeles to San Francisco to visit his family. Here, Raether describes one of his most memorable experiences using the service.

People who engage in Rideshare are, almost by necessity, a more open-minded bunch, less dogmatic about life and its prospects, largely reasonable. It’s hard to be doctrinaire about things when you take a complete stranger in your car for six hours. And many of the drivers I’ve ridden with are women. When I tell people this, generally they are shocked. But Ridesharing is different than hitchhiking. You answer the ad on Craigslist, they get your phone number and email address, they can see who you are by looking you up on Facebook, and they talk to you on the phone to get a sense of who you are. The main attribute you both are looking for is this: Is this person gonna be cool about the ride? For me, I’m just trying to get to San Francisco or LA. I’m not looking to get into a big political or religious discussion, I’m not looking for a lifelong friend, and I usually don’t even get a last name.

In April, 2011, before we both left Los Angeles, my daughter Saskia and I made our last Rideshare together up to the Bay Area. This one ride was the fitting coda for both us about the years we endured, together and apart, as a father and a daughter since my wife and I separated.

“Who is this guy we’re riding up with?” Saskia asked, as we sat at the Universal City Red Line station waiting for our ride up to San Francisco. Saskia — who was heading to college in the fall — was joining me because her big sister, Sasha, my eldest, was coming from New York to visit friends in San Francisco, and this probably would be the last time Saskia and I would ever make this trip.

“His name is Juan Carlos,” I said.

“Juan Carlos what?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “That’s all I got.”

“Why is he going up to San Francisco?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“You don’t know his last name, you don’t know why he’s going up to San Francisco,” she said. “Good job, David.”

“He sounded nice.”

“Great,” she said. “He’s probably a gang-banger. And he’s probably going up for a gang meeting.”

And then she laughed.

Joking about a man named Juan Carlos was something that came easily for Saskia because she was fluent in Spanish and had grown up in Los Angeles. The stew of languages and cultures that she swam in every day was normal for her. Virtually everyone she knew was bilingual, and not just in Spanish: Mandarin, Armenian, Russian, Arabic, and on and on.

She was being ridiculous about Juan Carlos, of course, but she did point out one of the basic problems with Rideshare: you really have no idea who you’re going to end up spending the next six hours with. For all you know, it could be Charles Manson. Or an Amway distributor, which is its own special form of torment.

When I talked with him on the phone, Juan Carlos hadn’t sounded like a serial killer, or a gang banger, or dangerous at all. He sounded like a very happy person, fun-loving, blithe, the sort of typical type of person the rest of the world imagines living in sunny Southern California: young, vaguely foreign. I liked him because on the phone he laughed easily at most things I said, funny or not.

But I really didn’t know much about him. Which would be no big deal were I making this trip alone. On my own, I always figured if the ride sucked, I could get out anywhere and figure things out from there. After a year of homelessness I had discovered resourcefulness that I did not know I possessed. I now knew that I could be proverbially and literally dropped in the middle of nowhere and figure my way home. In whatever form that home might take. It felt somewhat like freedom.

But Saskia was joining me, and wasn’t really all that keen on the trip anyway. She would see her sister again in a few weeks anyway when the eldest three girls would come from the East Coast for her high school graduation, plus the trip meant she would miss two days of school near the end of her senior year, and, finally, the whole idea of ride-sharing with her father must have irritated the hell out of her. Simply saying “Trust me, Saskia,” to a girl who had seen her father lose her childhood home, I’m sure pushed her normally trusting nature to the outer reaches of its elasticity.

I tried another approach.

“Saskia,” I said in my well-practiced father-knows-best tone, “Some day, maybe when you’re in your thirties or forties, you’re going to tell your children about the Rideshare trips you took to San Francisco with your father. And your kids and everyone else you tell are going to think they’re such incredibly cool stories and they’re going to love hearing about it.”

“Somehow I doubt it,” she said, and then scowled and curled up the right side of her upper lip.

A moment later, Juan Carlos pulled up in a three year-old Hyundai subcompact that had not been packed with the greatest of care. The left side of the back seat area was stacked high with clothes, books, shoes, a guitar, and the other clutter of a life lived casually. There was room for Saskia and possibly room for her backpack if we just rearranged things a bit. “There we go! Plenty of room,” he said. Saskia stared blankly at him.

“Sorry it’s a little crowded, but you’re slender,” he said to her with a goofy smile. That got her to smile.

He had on a T-shirt and track pants and wore his hair long and looked to be about 25. I bet he’s from Argentina, I thought, because I love Argentine soccer, and many Argentine soccer players have long hair. I have wanted to go to Argentina since before I was born. But I probably never would, so getting a ride from an Argentine was about as close as I would ever get to the country I had dreamed of visiting since watching the 1978 World Cup and deciding it was my true homeland, the way a dreamy twenty-two-year-old English and philosophy major from Minneapolis might do.

I looked back at Saskia. She glared at me, the way an angry 17-year-old girl whose father had completely screwed up her life might do.

“So,” I said to Juan Carlos once we were on the freeway, “Tell me about yourself.”

Maybe he could get that upper lip to unsnarl. I was long past capable of that.

Juan Carlos was not 25, as I had guessed; he was 38. He was originally from a village in the Michoacán state of Mexico, but he had lived in the United States since he was 14. His village was outside the big Mexican city of Morelia, and his had been a happy childhood. His parents owned farmland and raised sugar cane, and he lived in a nice house on the edge of the village. They had horses and 25 head of cattle (whom he knew, each of them, by name.)

The family had three dogs: two Chihuahuas and an unspotted, all-black Dalmatian. I’d never heard of an all-black Dalmatian. Maybe it was just a big black dog that he had decided was an extremely rare all-black Dalmatian because people like to make things up about their lives sometimes to make them seem more interesting. The Dalmatian’s name was Negro.

Negro, he told us, lived to be 20 years old. Or maybe he wasn’t. You never know how old a dog is, he said. They live their lives the way they want to.

In Mexico, he said, we think about dogs differently than in America. In America, people think about dogs as members of their families. Americans have to raise the dog, train him, teach him, feed him and care for him, as if he were a baby joining the family. In Mexico, he said, dogs are our best friends. They may live with you, but they can take care of themselves. They find their own food, they wander around all day with their other dog friends, and at night, they come to visit you, like a friend would.

In the mornings, the dogs would leave the house, sometimes anticipating where Juan Carlos and his father and brothers would go during the day, and the dogs would come along. He said at nights, after working in the fields, when it was time to bring the cattle in, his grandfather would whistle and the Chihuahuas and Negro would come up to the men on their horses. His grandfather or his father would tell the dogs it was time to bring the cattle in. And off they would go.

“Wait a minute,” I said. “You used Chihuahuas for herding cattle?”

“Yes,” he said. “They are very good at it. Dogs can do anything. They don’t just do what you think they can do, they can do much more.”

I looked at Saskia and she was smiling. Juan Carlos’ beguiling tales of village life in Mexico were softening her. The idea of Chihuahuas herding cattle seemed particularly amusing.

It was a good morning for a ride. We were coming up to the Tejon Pass and the sky was clear and the hillsides were still green from the winter rains and snow. It was sunny, but it wasn’t yet summer. The air was still cool, and when I rolled down the windows it was fresh and smelled good. This was going to be a happy ride.

“Do you have brothers and sisters?” I asked, wanting to expand the conversation, wanting Juan Carlos to tell us more about his life.

“There were five boys and then my sister came.”

I smiled, thinking of my six girls and two boys. “Oh, man, your sister must be the princess of the house.” I laughed a fatherly laugh.

“Well, actually, my sister passed away,” he said.

“Oh, that’s terrible,” I said. “What happened?”

He got quiet for a moment, and I looked back at Saskia, who suddenly had a concerned look. I rolled up the window because I didn’t want the noisy sound of rushing air to interrupt. He took a deep breath.

“When I was 12 years old, my sister, my mother, my father and two of my brothers were killed in a car accident. My thirteen-year-old brother and my seven year-old brother and I weren’t in the car; we weren’t there when it happened.”

Saskia had a stricken look on her face. This just seemed so wrong. Silly, light-hearted Juan Carlos with the cattle-herding Chihuahuas and the 20-year-old Dalmatian, suddenly seemed to both of us to be a different sort person all together.

“I just… I just can’t imagine that,” I said.

Juan Carlos stared ahead at the road. We drove for a moment, and I started to feel bad for pressing the point. But he continued.

“It was hard,” he said. “I mean, I was just a kid.”

“How did you come to grips with it? I mean, how do you get through something like that?”

“There were two moments,” he said, “that sort of pushed me through it. The first was when my uncle told my two brothers and me what had happened. I felt a strong rush through my body, like I was high on the most powerful drug possible. I just felt so light, like I was flying.”

“It must have been adrenaline,” I said.

“I don’t know,” he said. “Maybe it was adrenaline. Or maybe it was their spirits moving through me. I just don’t know.”

The way he said this made me believe the second guess was correct.

“The second moment happened on the morning of the funerals. I was showering and, when I finished, I reached out for a towel.” He took a hand off the steering wheel and made a grabbing motion. “But there wasn’t one there.” He paused. “That’s one of the things my mother always did. She was always making sure there were towels in the bathroom and soap and little things like that.”

“And then I realized that this was the rest of my life. No one would take care of me. I was alone in the world. I would have to take care of myself. And no matter what happened to me, good or bad, I would have no one to share it with. I couldn’t come home and say: ‘oh, listen to what happened to me.’ Because there now was no one there to listen. No mother. No father. No older brothers. No little sister.”

David Raether’s book can be purchased on Amazon in paperback or for Kindle. Please consider supporting the author by purchasing his book.

We took this in, and it felt as if the car moved silently through the mountains for a while.

“Juan Carlos,” I said finally. But my voice trailed off. “It’s hard to survive bad things, isn’t it?” I said.

“But you have to do it,” he said. “You just have to go on.”

And he did. Two years after the crash that killed his family, when he was fourteen, he left for America. He said he just had to leave the village, with its herding Chihuahuas and Negro, the black Dalmatian, and sugar cane fields and the smell of cooking coming out of the windows in the late afternoon as he walked home from school.

He went to stay with an aunt who lived in Long Beach. He didn’t speak a word of English. He was an illegal alien. One of the seemingly endless sea of illegal aliens that some believe are clogging the schools, streets, hospitals, restaurant kitchens, construction sites, auto repair garages and strawberry fields of California. Juan Carlos taught himself English, took up skateboarding and the piano and the guitar. He read novels in English and became a musician. He drove for Fedex for 10 years, then worked his way into television production, one of those guys on the stage dressing the set. He was gradually becoming someone new. I have become, he said, some kind of an American.

“I am Mexican in my soul,” he said. “But I have become American in my soul, too.

“My brothers came a year after me, but they left,” he said. “They couldn’t take it here. But I wanted to be here. I wanted to make a life here. And I did.”

“Do you ever go back?” I asked.

“I couldn’t for a long time because I was, you know, illegal. But when I was nineteen I went back for the first time.”

He described returning to his village. It looked as it did when he’d left: small, familiar, dusty and warm. He walked along the streets for a time, looking into shops and greeting people. He turned a corner and in the near distance saw a dog. It was Negro. They both stopped and appraised each other, and then Negro trotted up to him, wagged his tail , and leaned against Juan Carlos, waiting for him to scratch behind his ears.

“I bent over and whispered his name, and he leaned closer to me. ‘Negro,’ I said. The old dog leaned even closer to him, pushing his chest against Juan Carlos’ legs, lifting up his head and looking at the boy who was now a man with a deep voice and different clothes.

The image of that scene, Juan Carlos and Negro standing on a street corner, best friends reunited after many years, silently leaning against each other, felt like I’d just watched the climactic scene from a movie. In the backseat, Saskia was crying quietly, and I rubbed my eyes as well.

“You survived,” I said softly, not wanting to break the spell of his story.

“Yes, I did,” he said. He looked at me and smiled. “I am overqualified when it comes to survival.”

For the rest of the drive, Juan Carlos and I talked non-stop, about agriculture in Mexico, about the Revolution and Zapata and Pancho Villa, about books he had read, and the woman he loved, now waiting for him in northern California. We listened to music he composed and recorded. Several days later, he would email me links to two of the songs. I asked Saskia to translate them but she told me she didn’t want to. They were too sad, she said. They were about losing someone and not being able to find them.

But I have to say, the Juan Carlos we met in that cramped Hyundai was a happy person. He smiled most of the way, had a dozen projects he intended to pursue, was in love with a woman, and wanted some day to marry her. “I live my life the way I want to,” he’d said. “The past is always there, but I wouldn’t be who I am without it.”

He’d also told us a story about going for a run several years earlier. It was a rainy morning in Los Angeles, and he was running through a park. Suddenly, he said, he felt overcome with sorrow, so he stopped and leaned against a tree. “I felt like they were all there, in the tree, he said. My mother, my father, my brothers and my little sister. I could feel them saying to me, ‘Go on, Juan Carlos, we are here with you. Just keep going on.’

“And so I do,” he said. “That’s what I do.”

We arrived in Oakland about six hours later. He dropped us off at the Grand Lake Theater in Oakland where we were to meet Annie. Saskia and I stood for a moment and watched him drive away, not saying anything.

Finally, she looked at me. “That was a wonderful ride,” she said.

“Yes it was,” I said. And I put my arm on her shoulder and we stood together.

David Raether is the author of Tell Me Something, She Said, and a former TV writer on shows like Roseanne. He currently resides in San Francisco.

Photo: Faramaz Hashemi

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments