How a College Freshman Became One of Pinterest’s First Employees, Then Walked Away to Start His Own…

How a College Freshman Became One of Pinterest’s First Employees, Then Walked Away to Start His Own Company

by Beth Hillman

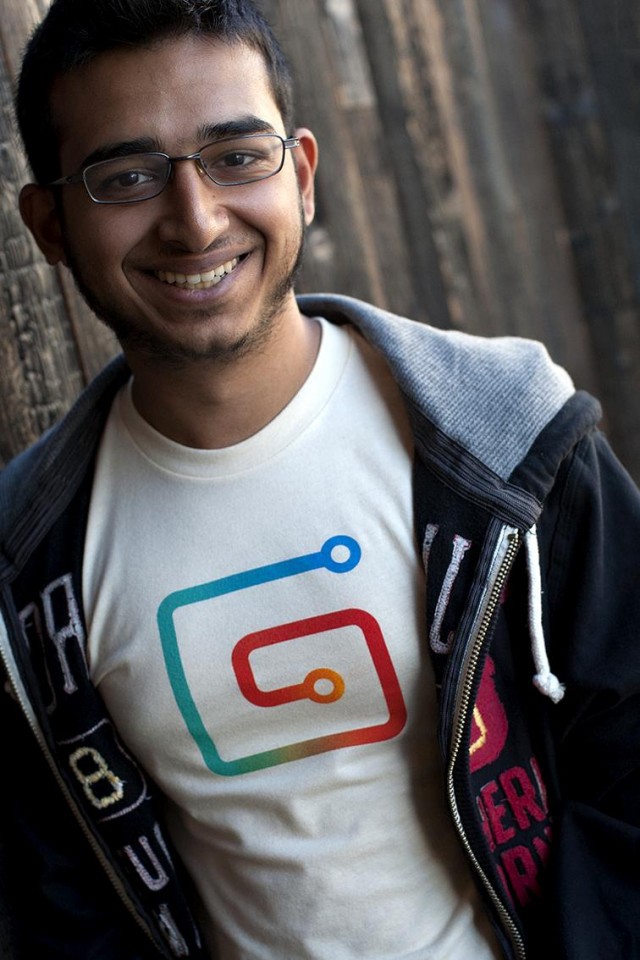

In 2010, Sahil Lavingia was recruited to become the fourth employee at Pinterest, then a little-known website. Being handpicked to help develop a site that is now used by millions is impressive in itself, but the accomplishment is made all the more remarkable by the fact that, at the time, Lavingia was an 18-year-old freshman at USC.

Lavingia said he began working to create apps in high school, then grew a following on his blog and social media accounts when he started college. About a year after joining Pinterest, Lavingia left the company to found start his own: Gumroad, a website aimed to allow people, especially those in creative fields, to sell what they create directly to their audiences.

I sat down with the 20-year-old CEO in Gumroad’s cavernous Potrero Hill office space in San Francisco to discuss his career path and how he came up with the idea to start his own company.

Beth Hillman: How did you get started at Pinterest?

Sahil Lavingia: Very quickly after I got to USC, I started doing work for startups and building stuff for fun. I sort of started that while I was in high school — learning how to design and make apps for the iPhone. But when I got to USC, I started caring about telling people what I was doing rather than just doing it. I started a blog, tweeting. The rationale was that: I’m in California now, and this is where all the cool stuff happens. That led to Ben from Pinterest seeing my stuff and saying, “Hey, we’re a three-person company based in Palo Alto, we need help on these things. Your work looks pretty cool.”

BH: It amazes me that he would reach out to you, as a freshman in college.

SL: The difference with tech is that you can produce professional quality work — there’s no barrier to that — as long as you have a laptop. It’s up to the market to decide if what you build is interesting or not. The market doesn’t know how big the company is, or how old the CEO of the company is. So, that’s sort of the sexy example because it led me to joining a company that’s now 180 people and worth billions of dollars on paper.

BH: So he asked you to join and you dropped out of college and took the job. Were you at all freaked out by that, or was it a no-brainer?

SL: My idea had been that I was going to spend four years in college, get my degree, then probably join a medium-sized company, then a startup, and then probably start my own company. So if my goal is to join a startup, and I have this opportunity to do that today, I thought I could try it for a year. If it were to blow up in a bad way, I could always go back and there wouldn’t be that much that I lost — and I would have learned a lot. I think it was a pretty risk-free decision.

BH: You were at Pinterest about a year, and that’s when they started to get really popular. So what was the mindset for you to leave and start your own company?

SL: I wanted to see if I could start a company. That was my original goal. Pinterest was doing really well, that’s true. And there were people who were really excited about me as an individual. Like, “What are you going to do next? You’re a kid.” For me, I really wanted to see if I could build something myself. And also the idea was really addicting to me. I had a bunch of ideas, but Gumroad was the first idea I felt like I could work on for a decade. The whole reason I got into making stuff was because Apple let me charge for stuff I had made. It made it possible for me to make a living making stuff. With Gumroad, I feel like we offer that opportunity to all these creative professions that don’t really have that. If you’re a musician, a designer, a photographer, it’s still not that easy to take that skill set and turn it into a career.

BH: I read an interview in which you discussed creating an image of a pencil as something that inspired Gumroad.

SL: I was designing an icon of a pencil in Photoshop. It took me like four hours or something — I wanted to learn photo-realistic 3D icon design. So I finished it and thought, “OK, that’s really cool.” The only problem was that I spent four hours learning how to do this. It would have been really cool if I had a similar asset four hours ago. So this thing that I made might have value for someone else. I tried to go and sell it. Turns out, it’s pretty difficult to put stuff for sale on the Internet, especially if you’re basically a nobody. But I was like, I have an audience and I have this thing I want to sell to them, why am I not able to? It’s less about the monetary aspect, but it’s more about the idea that, if we can help people make money, we can help them spend more time doing what they love. At the end of the day, if you’re a musician, the goal is to make enough money making music so that’s all that you have to do.

BH: Was it an easy decision for you to leave Pinterest?

SL: That was harder than leaving college. There were a bunch of things that made it easier. The market to start a company and raise money was really, really good — I think the peak of the past few years — this was September 2011. I was confident I could raise money, and almost immediately investors were like, “This is pretty cool.” And, as I said, it was what I wanted to do. I could figure out if I would be good at founding a company. Maybe I would have just hated it. What if I went through all these steps and finally I had the skillset to go start a company, and then I realized, Actually, I really don’t like doing this. It would have been nice to have found that out. I feel like the biggest risk in life is waiting.

BH: That addresses another question I had about raising money. So I guess if you have worked for a company like Pinterest and already have your name established, people will come to you with money?

SL: You should never assume that it’s going to happen. People say, “I want to start a company.” Why? I started this company because I really wanted to build this thing and the best way to do that was to start a company around it. A lot of people I think start stuff, especially now that it’s a little easier, thinking, “I want to start a company and sell it to Twitter for 10 million dollars.” I don’t know if I like that.

BH: Is it challenging to be dealing with these different kinds of issues — hiring people, managing people, figuring out all the aspects of running a company — at such a young age, especially after only having worked at Pinterest?

SL: It’s definitely hard, but I don’t know how much it easier it would have been. You never know how hard starting a company would be because it’s a different problem set than any other role you could have. At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter how old you are or how many years you’ve worked professionally, it’s such a different thing.

BH: Do you ever feel like you missed out on college or feel like, I wish I could be having a beer and writing some stupid psychology paper right now?

SL: I can have a beer and not do the psychology paper. I definitely missed out on stuff. It’s like a cost-benefit thing. One of the things that’s specific to me is that because I went to high school in London and Singapore where the drinking age is lower, you sort of get that experience earlier. Honestly, it made it easier to leave college because I felt like I got a lot of that experience.

BH: I guess more of what I mean is that you have so many responsibilities, a kind of pressure that most 20-year olds don’t have.

SL: I remember this one moment when we had to set up some kind of payment thing and an engineer asked for a password to log in and he was like, “Dude, there’s like eight million dollars in this bank account.” And I was like, “Yeah?” And he was like, “Really, there’s like eight million dollars in this bank account.” Maybe I’m just different, but I never thought that was weird. Looking at it rationally, I guess that’s kind of strange. I think when you are forced to combat a situation your brain gets used to it quickly. After a point, it’s like the new normal.

BH: In another interview, you said something about Gumroad lowering the bar of what is something meaningful and valuable to someone. Can you expand on that?

SL: A very common equation in commerce is: “Conversion = desire — friction.” The chance that you end up buying something is how badly you want it minus how hard it is to actually get it. The amount of time, effort, amount of keystrokes… I think if you can lower the friction, you can also lower the minimum amount of desire that you need. Typically on the Internet, you won’t find anything for sale for 10 cents. Almost always, the barrier to entry to buying something on the Internet is worth more than 10 cents to you. So if you have the ability to make things frictionless to buy and more people than ever before flowing through this system, it might be possible to lower that minimum to zero, so that anything that has value you would be able to execute. I think getting the barrier to zero will take many years, but we’re getting closer.

BH: And it seems like people have had great success with this model. Can you share any examples?

SL: We have this one seller who used to be a freelance designer and he had a blog and decided to write a book. I think his first book made $40,000 or $60,000. Now, the number he’s made is $200,000, in about a year. It feels amazing to help make that happen. And the goal is to make that happen a million times more. His life is different because of Gumroad, which is really cool to think about. There are writers, filmmakers — lots of people have made a lot of money. Because this now exists, I want to challenge people to think, “What is the ideal way I can make a living?” If I love teaching people about math, the traditional option to do that five years ago, 10 years ago is to become a math teacher. Today it’s very different. If you want to teach math, there are a lot of ways to go about doing that.

Beth Hillman is an editor and freelance journalist living in San Francisco. She previously wrote about Umami Mart.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments