The Tanda System

by Lynn Vollbrecht

I tried to rearrange my face into something that read “Here I am content in my firmly drawn boundaries but possibly interested in reconciling if you agree to my terms.” The fight that had finally broken us all the way up was still fresh. We were only a week past the night when he left the house, moved out. Permanently. I had a speech prepared, my terms drawn up, game face on.

“I have some things to say,” I said.

“First, let me tell you something,” he replied. “Because you’re going to be mad.”

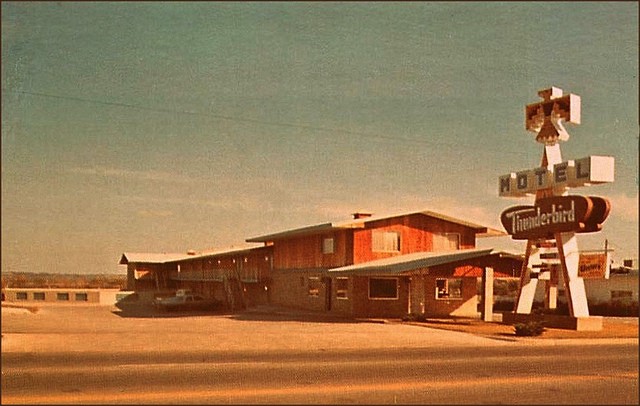

He had been staying in a cheap motel, the kind that doesn’t try to be anything but — whose cheapness is its primary selling point. On some level I knew what he was about to tell me, because I, the person who could tell you the balance to the dollar on any one of my financial accounts on any given day, who logged in and looked at the numbers and checked balances as routinely as my morning coffee, had avoided looking at that particular credit card balance that week. He wouldn’t, I told myself. He would never mess with my money. He KNOWS how I am with my money.

“I know how you are with money, so I wanted to tell you: I’ve been paying for the hotel with the card,” he said. I saw red, and my carefully composed face contorted. He was a cardholder on one of my accounts, it’s not like he had done something illegal. Just something that got me — a person who equates financial stability with freedom, with possibility, with essential self-reliance — where he knew it would count. You can trample on my heart, I guess, but don’t you dare mess with my credit score.

“I’ll pay you the money,” he said, in a rush. “I would never take your money.”

I can kiss that money goodbye, I thought, all reconciliatory measures draining away. Funny that this was the thing that finally made me angry — funny that he did know me so well. “But how are you going to pay me back if you don’t have that money in the first place?” I asked.

“I’m doing a tanda,” he said. “When I get the tanda I will give it all to you.”

The first time I ever heard of tanda was from him, and I thought it was a pyramid scheme. We’d been planning a vacation, and I was worried about funds. “Let’s put it on the card, and pay a little each month,” he suggested. I protested, citing the interest. “Let’s save a little each week, and pay in cash,” I countered.

“What about a tanda?” he suggested.

“A…what?”

“Tanda.”

He explained: You get a group of people together, with one person as the head, the organizer — for the ones he was in, it was the head chef of the restaurant where he worked. Say you have 10 people. You put the numbers one through 10 in a raffle, have everyone draw a number; each number represents a week. When your number comes up, when it’s your week, everyone pays you a set amount of money, $100, say. The other weeks, you pay $100 to the designated person. You take turns receiving the money, and when you’re not on the receiving end, you’re paying in.

“Oh, so you just give money to the next person on the list, and then money comes back to you? THAT’S A PYRAMID SCHEME,” I scoffed. “Haven’t you ever seen that episode of every sitcom ever, where they call it a trapezoid scheme and pretend like it’s not a pyramid scheme?” He hadn’t. “This is like that. Just because you call it a tanda doesn’t make it not a pyramid scheme.”

It turns out, it’s not a pyramid, nor a trapezoid. It’s a circle.

Back in 2004, a group of anthropology students at the University of California, Irvine produced a paper on tandas as part of an exhibit on the anthropology of money. The official term for tanda is a “rotating credit association,” theorized to have begun in rural areas, possibly adopted from Chinese immigrants to Mexico. There are equivalents in other cultures, and often it’s a practice utilized most frequently by women. It is, the authors (Rosalba Gama, Delma Medrano and Luis Medrano) wrote, “a monetary practice that we, as Chicanos, have grown up knowing but never really understood in any depth, except that our parents or other relatives participated in them.” Like me, they seemed enamored by the idea of this inherent trust in the tanda process.

“Confianza, or trust, is the key aspect of the tanda and is what allows this type of credit association to exists within the community,” they wrote.

My exes have introduced me to now-favorite bands, previously-unknown-to-me writers, oyster omelets, and to amazing friends with whom I remained close. In this particular case, I got a fairly thorough intercultural education. Despite having lived in a city with a sizable Hispanic population for much of my adult life, dating a Mexican who was part of that tight-knit community exposed me to a side of my home that I hadn’t even realized existed.

Some of it was already vaguely familiar, but suddenly I was learning how to cook chicharron and make micheladas, watching him sing Juan Gabriel at karaoke and seeing his sisters cry over Jeni Rivera’s death, and picking up stray pieces of Spanish slang and winging away to the outskirts of Mexico City for Christmas. And learning about tanda — about a communal trust that I couldn’t, and still don’t, comprehend.

Even after I had gotten over my initial reaction to tanda, I couldn’t suspend my disbelief that people would instill that much confidence in each other, with regard to their money. After we moved in together, my boyfriend and I never combined finances in any significant way, but I did get him a card on one of my credit card accounts, in order to help accumulate airline miles and build his credit. He usually bought gas or groceries and handed over a cash reimbursement within a few weeks. I usually squirmed a bit in the meantime. He always paid me back.

I sat down with him and the regular head of his tanda, once, to try to understand the idea of a revolving credit association. At the time, the three of us — my boyfriend, the chef, and I — all worked in the same restaurant.

In Mexico, it’s how it’s always been done, they said. Everyone knows what it is. Why not just put your money in a bank? I asked. “Why not just do a tanda?” they said, where you’re beholden to other people and can’t avoid handing over the money, when others are relying on you. Can women be in a tanda? “Of course!” Gringa women? They remembered one a while back — “Why don’t you join the next one?” they said. “Anybody can join. Everybody can feel happy in ten weeks,” the chef, the tanda’s head, told me. People have a favorite position in the cycle, usually; the busboy likes to take two numbers, they said, the last two. The head of the tanda, who has to pony up if someone can’t make his or her payments, automatically gets the first number or first choice of which number he’d like. Sometimes people buy an earlier number, pay to swap.

But what if someone is not trustworthy? They shrugged. “Then they get the last numbers. Or they don’t get to be in the next one.” It was making sense, but I still couldn’t wrap my head around it. Haven’t you ever known anyone to get screwed in this process? Oh sure, they told me. Like that girl who walked into that kitchen they used to work in, walked in and paraded an exposed thong and walked out with several hundred dollars collected from the smitten cooks under the auspices of starting a tanda, never to be seen again. They chuckled at the memory.

He had not only paid up front, in advance, for the motel room for several weeks, he had used the card to make a sizeable cash withdrawal from his bank, incurring a fee. Fuming, I tallied the total and texted it to him. The tanda would be a little short, he said, but he’d make sure I got every penny, eventually. I had called the credit card company after our first conversation, late at night. “Can you get the card back that you want to cancel?” the customer service rep asked. “No,” I said. She was cool and professional, and told me they’d issue me a new card.

Every text from him over the next few weeks was met with the same embittered response, from me: “why don’t you pay me my money?” It was close to a grand, in all. I told him if I had to spend $800 in claims court to try to get it back and only recoup $200, I would. I imagined him rolling his eyes.

A month later he handed me an envelope, as we stood in the middle of the street next to his idling car. “Count it,” he said. It was $800, cash. I already knew I would not pursue the rest, I just wanted to cut all of our remaining ties. The look on his face said that he did, too — that he couldn’t believe I hadn’t trusted that he would pay me back.

Lynn Vollbrecht is a writer and editor in a committed relationship with her credit score. Photo: 1950s Unlimited

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments