Why Don’t I Give Money to Poor People?

by Michael Hobbes

“Hey, you want necklaces? I sell you necklaces!”

He’s dishevelled, but not more so than most people you see on the street here. He’s wearing a bright green soccer T-shirt, a team I’ve never heard of, and a goatee. He introduces himself as Paul.

This is Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe. I am backpacked, sunglassed, earbudded, on my way to the waterfall. The only way I could be more obviously a tourist is if I had a fanny pack and an “I ♥ Zim” T-shirt on.

“Thanks, but I’m not interested,” I say. I may have actually physically waved him away.

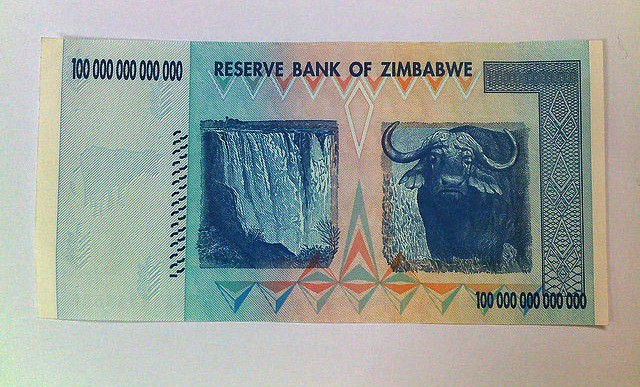

He walks with me for a few minutes, pushing necklaces, wooden giraffes, 50 billion Zimbabwe dollar notes into my chest. I repeat the same thing: Sorry, not interested. Sorry, no.

Everywhere it’s different but the same. In San Francisco it’s the guy who could visit his sick sister in Portland if he could just get 10 bucks for the bus fare. In Paris it’s children with their arms out. In Istanbul it’s amputees on a sheet of cardboard, literally begging.

And my answer is always the same: “Sorry.” I don’t know when I started saying this, when I stopped bothering to lie about being out of spare change, when I stopped thinking before I said it.

Right after Paul peels off, I take what I think is the turnoff to the falls. The path peters out, I turn around and when I get back to the road, Paul is there.

“Where are you trying to go?” he says.

“Just to the park entrance,” I say.

“Oh there’s a shortcut just up there to the right,” he says. “It’ll only take you five minutes. Make sure you make it to the gorge before dark. Spectacular, man, spectacular!”

I thank him, and realize that as he was talking I was thinking oh, he’s a person.

You’re not supposed to give beggars money. That’s the conventional wisdom, right? You don’t know what they’ll spend it on, you might be encouraging them to stay on the street, you’re not addressing any of the structural issues that got them where they are. I used to live in Copenhagen, and whenever I got panhandled (yes they have panhandlers in Denmark), I wanted to roll my eyes, like, all this free money in your country and you want mine?

Needless to say, that attitude is a lot harder to maintain in Zimbabwe. It’s even harder to maintain for me, considering I am here working for a human rights organization. How do I justify spending two weeks in Harare attending conferences, meeting NGOs, working on statements and recommendations to make this country less poor and then, the minute I’m on vacation, neglect to do the one thing I’m actually equipped, actually qualified to do: Give it some fucking money.

The sun is setting when I come out of the park, and Paul is at the exit, soliciting another tourist. He sees me and breaks off.

“How was the park, my friend?” he says.

“Good,” I say. “How’s business?”

“Not so good today,” he says, the full bouquet of necklaces still dangling from his hand. “Look, can you help me out, just with a dollar? I’m hungry.”

I feel like Paul has taken his mask off, he’s talking to me outside of his role as a street vendor, like we’ve both stepped out of character for a second and it’s just us, man to man. I give him two bucks. He thanks me profusely, leaves without asking for anything else.

Two hours later I see him again. This time I’m on a trail behind Victoria Falls’ fanciest hotel. I’ve just eaten a French croissant pudding that cost 7 times what I gave to Paul.

“My friend!” he says.

“Hi Paul,” I say, weirdly happy to see him. I’m travelling alone, and he’s the only person I’ve spoken to all day.

“Hey, do you have some dollars for me?” he says.

“I just gave you two,” I say.

“But I ate with those, man,” he says. “Can you give me some more for dinner?”

As much as I hate to admit it, this irks me. I already gave you money, dude, coming back for more just makes me feel like a mark — like this is a business model. If you don’t get tourist money with merch, get it with sympathy.

“Sorry,” I say.

Later, I wonder what outcome I was actually trying to protect myself against. Giving money to someone who is demonstrably worse off than me? Maybe Paul used that money to buy himself lunch, maybe he didn’t. What am I, USAID? Who cares what he spent it on. If those two dollars (or 10, or 20) magically disappeared from my back pocket, I never would have noticed. Why am I Jay Gatsby when it goes to making me better off, but Ebeneezer Scrooge if it does that for someone else? All that shit about enabling, it’s just an excuse for me to keep what I feel is mine.

In development circles, everyone is all excited about this “just give money” thing. The idea is: Poor people know better what to do with their money than we do, so if you want to help, don’t tie a donation to some entrepreneurship scheme, behavior modification, Excel-sheeted output, just hand over some scrilla, no questions asked.

Apparently it worked in Uganda, another country I have visited to do development work in the daytime and say “sorry” on evenings and weekends. If this idea is real, maybe I should be refusing all the conferences and acquiescing to all the beggars.

I have no idea what I should do. When I travel to developing countries for work, should I set a daily amount that I can afford, say $20, and hand it out randomly? Should I start donating regularly to charities who do that? What is, as the MBAs say, “best practice”?

I am in Victoria Falls for two more days. I will probably run into Paul again. He will probably ask me for money, and I will probably give some to him. I might even give him enough to try that French croissant pudding.

Michael Hobbes lives in Berlin. He blogs at rottenindenmark.wordpress.com. Photo: bfishadow

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments