What Would Jesus Do About Gentrification?

by Jon Custer

Every year on Good Friday Catholics around the world celebrate the Stations of the Cross, a ritual which traces back to early pilgrimages to Jerusalem. Usually the “stations” are a series of small plaques, reliefs, or statues inside a church, but in many parts of Europe networks of small shrines were set up around various cities to allow the faithful to make their own mini-pilgrimages without the expense or danger of traveling to the Holy Land.

My local Catholic church in Washington, D.C., however, has taken a more radical approach, using the story of Christ’s betrayal and crucifixion as an allegory for the changes gentrification has wrought on our neighborhood. Usually, this is done at holy sites, but in this case, the church stops at food banks, AIDS clinics and other local establishments in our rapidly gentrifying neighborhood and talk about the need to preserve social services and provide more affordable housing.

Saint Augustine Catholic Church, now located at the corner of NW 15th and V Streets, is itself a product of the city’s tumultuous history of racism, white flight, and economic revival. As “the Mother Church of African-American Catholics” it has long been a home to people who felt shut out by Washington’s white establishment.

Though the Catholic church renounced racism in 1958 and participated in the Civil Rights movement, the views of individual Catholics — including many in the clergy — obviously took longer to change. (After a very post-Vatican II Easter Sunday service, featuring a gospel choir and dancers, I heard an elderly white man complaining to his wife in Polish about the “jazz.”)

Moved from its former downtown site in 1947 to make way for the Washington Post building, symbols of D.C.’s complex racial politics are everywhere at Saint Augustine, from the African features of the Jesus on the crucifix to the historic pews placed proudly in the front row. They were once reserved for blacks forced to sit at the back of a Catholic church in Georgetown.

These days, though, Saint Augustine mainly worries about the poor and disadvantaged of all colors (but who are, let’s be honest, mostly black), it feels are shut out of the city’s revitalization. Its Stations of the Cross program, which has been running for years, is a reflection of those concerns.

Note: Each quote is taken straight from the Stations of the Cross program.

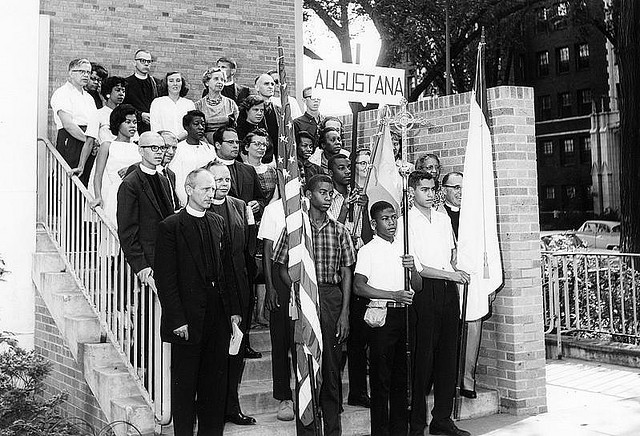

1. The First Station: Augustana Lutheran Church

Augustana Lutherans preparing for a civil rights march in 1963. Photo: elcaarchives

The Lutherans are one of the Protestant denominations that also celebrates the Stations of the Cross in the Catholic fashion. And Augustana has other things in common with its Catholic neighbors than sharing a saint: “Though founded by Swedes and Swedish-Americans, as you look around, you will see light and dark skins. Augustana was among the earliest churches in Washington, D.C., to racially integrate in 1954,” says the church’s About Us page. “Augustana has embraced inter-racial marriages that blend African, African American, Asian, European and Latino-descent individuals into couples.”

Unlike Saint Augustine, though, Augustana also proudly performs same-sex marriages. Washington-area churches of all denominations were barred from conducting interracial marriages in Virginia and Maryland until the famous Loving v. Virginia Supreme Court case of 1967, while D.C. never had an anti-miscegenation law. Same-sex marriage is now legal in D.C. and Maryland, but remains banned in Virginia.

2. The Second Station: The Third District Police Station

Violence and crime in our neighborhood make the police even more important in helping us to maintain law and order. In recent weeks, acts of senseless violence remind us of how important it is to work for peace in our city and in our world.

The program repeatedly mentions rising crime rates, despite the fact that murders in “Dodge City” are at a 50-year low. What crime remains largely targets the poorer and darker-skinned residents of the more neglected neighborhoods, especially east of the Anacostia River, though the gentrified part of U Street has seen some recent shootings.

3. The Third Station: Meridian Hill/Malcolm X. Park

The park’s fountain as it looks today. Photo: Wikimedia commons.

Our gathering here at Meridian Hill/Malcolm X Park on Good Friday is one of the longest-standing events in the park. Over the years, the neighborhood has changed greatly, but the need for our care remains.

At a 1969 rally, Angela Davis proposed renaming Meridian Hill Park after Malcolm X, the black Muslim revolutionary who had been killed four years earlier. The change was never formally adopted, but the unofficial name stuck.

This was a difficult time for the city of Washington and the U Street corridor in particular: after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, riots swept the city and destroyed the once-thriving black commercial districts along U and 14th (as well as H Street NE). President Lyndon Johnson ordered Federal troops to occupy the citythe largest occupation of an American city since the Civil War — two weeks before Good Friday.

In subsequent decades, the park would become a visible symbol of the neighborhood’s decline and the city’s class and racial divisions, a public space full of crime and vandalism (a “supermarket of drug dealing” according to one 80’s cop) flanked by the indifferent stone facades and barred windows of stately mansions and embassies.

In 1990, neighbors organized a group called Friends of Meridian Hill Park to conduct safety patrols and began working with the National Parks Service to bring the park back to life, cleaning up trash, repairing statues, and hosting events. By 1994, it was safe enough for President Clinton to make the 7,000 foot journey from the White House and deliver an Earth Day speech there.

4. The Fourth Station: The Fedora Condominium

Gathered here on Belmont Road, we witness both the resurgence and the continuing problems of our neighborhood. New homes are a sign of hope, but the concerns of longtime residents and the poor have been excluded. We pray that services for the neediest among us will not be lost in the rush of resurgence.

Like almost every new development project near U Street, the Fedora’s name pays tribute to the area’s vibrant jazz history, presumably providing a veneer of cultural legitimacy to the new residents. Why did the organizers choose to focus on The Fedora and not another new condo — say, the nearby Ellington? Probably because it’s the former location of Pitts Motor Hotel, a black-owned hotel frequented by 1960s civil rights leaders.

In fact, Dr. King himself reserved 30 rooms at the Pitts during his final visit to Washington, two months before he was assassinated, for leaders of the Poor People’s Campaign he planned to lead later that spring. The campaign went ahead even after King’s assassination and the devastating riots that followed, setting up a 3,000-person tent encampment called Resurrection City on the National Mall.

Unlike today’s Occupy movement, they had specific demands: $30 billion for anti-poverty programs (equivalent to $195 billion adjusted for inflation) and 500,000 units of affordable housing constructed annually. They were dispersed with tear gas in June.

1,000 square foot two bedroom, two bath condos in The Fedora can be purchased for $600,000. The rooftop deck boasts panoramic views of Malcolm X Park.

5. The Fifth Station: Nehemiah Cooperative

Photo: prince of petworth

As the man from Cyrene helped Jesus carry his Cross, so must we help our sisters and brothers carry the cross of homelessness and inadequate housing. Nehemiah Cooperative assists the families in this community to become homeowners. Let us work with our government and community leaders to support the building of more housing for low and moderate income families.

Nehemiah is an interesting historical character with his own book in the Hebrew Bible, a Persian functionary of Jewish descent sent to rebuild Jerusalem in the 5th century. When he arrived, he found the city in economic chaos — people had been forced to mortgage their homes, fields, and vineyards to buy food. Enraged, he demanded that everyone (including himself) renounce charging interest and return the foreclosed properties to their rightful owners.

The Nehemiah Shopping Center on 14th Street NW featured a convenience store, a wig shop, and a Papa John’s. It was bought and demolished in 2006 to make way for yet another upscale apartment building (slated to open any day now) where you can “live in casual luxury” in a 500 square foot studio apartment for just $2,071 a month. “What could be better than a brand new apartment in Washington D.C.’s most vibrant neighborhood?” asks the building’s website.

6. The Sixth Station: Christopher Price House

How 14th and U Street looked in 1988. Photo from Michael Horsley via D.C.ist

How it looks on a typical Friday night today.

Jesus told the women of Jerusalem to weep not for him but for themselves and for their children. We gather here to weep for those who are in need of services of independent living facilities, like those of Christopher Price House. Christopher Price House/Belmont Apartments provides low income apartments for those with disabilities. Yet, the lack of affordable housing in Washington continues to increase and the solutions seem so inadequate. Le us work with our city leaders to ensure that the most vulnerable in our community, especially those with disabilities and the elderly, are provided with safe and affordable housing in our city.

In a weird way, developments like Christopher Price House may have helped to spark the condo boom that is now driving up rents along the 14th Street corridor between U Street and Columbia Heights. A 1998 Washington Post article written on the 30th anniversary of the ’68 riots suggests that nonprofit groups like Christopher Price helped to make the area safe for private investors scared off by post-riot neglect and crime.

These (often church-based) organizations, realizing that affordable housing was one of the biggest problems for the people they served, soon became de facto developers and landlords, doing what the private sector wouldn’t or couldn’t.

“By default, nonprofit groups even have become the new power brokers in the area,” the article says. “Next month, for example, the city will accept development proposals for 13 acres of land around the new Columbia Heights Metro station — land the city acquired from owners who walked away after the riots.”

That development, dozens of gleaming new shops and apartment buildings targeted at the city’s up-and-comers, is mostly built now. And nonprofits have indeed extracted a number of concessions, including supportive housing units for people coming out of homelessness right next door to high-end condos.

Having lived here only since 2011, it’s difficult for me to imagine 14th Street as the Post described it just 15 years ago. To me, Columbia Heights means Bed, Bath, and Beyond, not guns, crack, and prostitutes. But have the guns, crack, and prostitutes really disappeared, or just been pushed to other parts of the city?

7. The Seventh Station: Cardozo High School

White students in shop class at Cardozo, some time in the late 1910’s.

We look to Cardozo High School and just beyond to Howard University. We pray for all children who are fearful of the dangers and violence that have penetrated these walls.

In the early part of the 20th century, Washington’s D.C.’s all-white Central High School graduated notable establishment figures like J. Edgar Hoover and John McCain’s dad, but when it was designated a “colored” school it needed a new name. With more than a touch of irony, school officials chose to name it after Francis Lewis Cardozo, a clergyman and educator born in Charleston, S.C. to a free black woman, who advocated for integrated education during Reconstruction. (Strangely, this 60-page guide to the namesakes of various D.C. public schools, put out in 2011, doesn’t mention Cardozo at all.)

School violence first became a major issue in D.C. soon after the riots. In 1969, three teens shot and killed a Cardozo assistant principal and stole the school’s safe. In 1970, a 15-year-old Cardozo student was accidentally killed by another student who was showing off his gun at lunch time. This exact scenario has played out at least two more times in recent memory, once in 1995 and again in 2003. In the latter case the student, 16, was hit in the leg and survived.

According to the book Lockdown High, police were first brought into D.C. schools later in 1970 after reports of “racial violence.” In the 2007–2008 school year, following a complete restructuring of D.C. school safety under Mayor Adrian Fenty (and a new principal), the conservative Heritage Foundation said that Cardozo reported 18 assaults and seven robberies. The school is in the midst of a $100 million renovation scheduled for completion this summer, and remains a great place to watch fireworks.

8. The Eighth Station: Miriam’s House

Gathered here at Miriam’s House we are reminded of how vulnerable our lives are. Many people who are HIV positive, as well as many of those living with AIDS and other illnesses, are forced to walk alone. They feel abandoned in times of weakness and need. They fall into depression and give in to anger and resentment. But many women and children find help beyond these doors to regain sufficient strength to continue the journey.

After the 2008–2009 recession, Miriam’s House — a shelter for homeless women — merged with N Street Village, which provides mental health, housing, employment, and addiction counseling. “The merger may offer a glimpse into the future, as nonprofit agencies grapple with how to survive in an economy in which charitable giving has fallen and the need for services has risen,” the Washington Post said at the time.

9. The Ninth Station: Former location of Anthony Bowen YMCA

Here it is in 2012, and in 2011.

Many men, women, and children who previously used the Anthony Bowen YMCA were in search of a new life. Today we stand near a new building where it once stood, with promises by developers that a new YMCA will open in the near future and continue to provide the services that it previously had for this community. But often the needs of the poor in this community are neglected to advance the economic benefit of a few.

When developers bought the site, they promised to rebuild the YMCA bigger and better. The YMCA itself says the building, named for the founder of the first African-American YMCA, was “160 years in the making” — an appropriate descriptor for the long-delayed project.

When it does eventually open, it’s supposed to feature a pool, a (public!) rooftop terrace, a demonstration kitchen, an Internet cafe, and an interactive museum about Anthony Bowen, as well as the usual children’s play areas and summer camp programs. Check back next Easter!

10. The Tenth Station: Martha’s Table/Outfitters

Blink and they’ll be boutiques.

Bless the hands of those here at Martha’s Table who prepare the food for those who have nothing to eat, and those at Martha’s Outfitters who provide clothing for those in need. Place in our hearts the fire to serve all in your name. Free us from selfishness and materialism that keeps us from sharing our time and our possessions with those in need.

Martha’s Table and Martha’s Outfitters provide emergency food, daycare, and clothing to more than 1,100 people each day. Their programs are supported by donations of food, money, and volunteer time, as well as the proceeds of the Martha’s Outfitters thrift store. Somehow, they have survived the onslaught of development and high rent, continuing to operate alongside a boutique selling farm-fresh products from Lancaster, PA and a string of upscale restaurants that have popped up the in abandoned storefronts along the west side of 14th Street (even the gas station next door now sells amazing gourmet sandwiches.)

A store for people who think nothing of spending eight dollars on a bottle of organic milk next door to a program that provides food for people who don’t know where their next meal is coming from: this is 14th Street NW in a nutshell. This neighborhood is changing so fast that even Google Street View is hopelessly out of date.

11. The Eleventh Station: Former location of Twelve Step Programs

The former AM-PM Carryout. Photo from PopVille.

Men and women used to gather here every day, several times a day, to provide support and encouragement to one another to find freedom from the ravages of drugs and alcohol addiction to the blessing of sobriety. Now, they have been forced away in the name of progress and economic development. But what progress is there in our society when we deny healing and recovery to those in need simply to advance the economic benefit of a few?

The community programs next door to Martha’s Table weren’t so lucky. As you can see, this building also housed the AM-PM Carryout, one of the only U Street corridor businesses to survive the ’68 riots to the present day (the other notable example being D.C. landmark Ben’s Chili Bowl, which served as Stokely Carmichael’s headquarters during the riots.) Some people felt the AM-PM and AA/NA crowd didn’t fit in with the changing neighborhood. Here are their new neighbors across the way, for comparison:

The building was sold some time in 2010, forcing out Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, and the other community outreach groups that used to rent out the back portion of the building. Reports are that it will now become a Tex-Mex restaurant called Diego after the painter Diego Rivera, a lifelong Communist.

12. The Twelfth Station: Reeves Municipal Office Building

The Reeves Municipal Office Building stands as a testament to the commitment of our city government to work with our community. We pray that with dedicated and committed city officials and community leaders, we will find creative and positive ways to recreate our city’s hope, ending the scourges of addiction, poverty, illness, and abuse.

The convoluted recent history of D.C. city government is far too big of a topic to handle here, but let it be said that despite the many scandals and indictments, and despite the shady developer money that bankrolls most successful City Council members’ campaigns, the city’s government has generally been at least sympathetic those who would like to see economic development come with better services and affordable housing for the city’s poorer residents.

The Reeves Center building itself symbolizes an interesting stage in my neighborhood’s redevelopment. Built in the 1980’s at the urging of then-councilmember Marion Barry, who would later gain notoriety for being videotaped smoking crack while mayor, the sprawling government building was an early attempt to revitalize the U Street area.

It didn’t hold up so well. Architecturally, it looks somewhat out of place in a neighborhood so far characterized mostly by low-rise, mixed-used development. The inside isn’t much better. In a series of visits to the center in 2011, a City Paper columnist found leaky ceilings, questionable contracts with sketchy nonprofits, abandoned offices and furniture, and a bizarre convenience store in the lobby that owed $340,000 in back rent (I’ve been inside the building many times and can confirm that it is… strange.)

13. The Thirteenth Station: Formerly Campbell Heights Senior Citizen Apartments

Campbell Heights tenants shortly after “purchasing” the building. Photo: Washington Informer

As we stand before a building that was once Campbell Heights Senior Citizen Apartments, let us be mindful of our responsibility to tenderly care for our elders. May our churches and government always provide a stable and peaceful refuge for those who spent their lives giving us life. Let us not allow our city’s quest for economic development allow for the displacement of the elderly, who are often left without a voice or an advocate when they are at their most vulnerable.

What happened to the Campbell Heights Senior Citizen Apartments is a bit of a mystery. Built on the site of the famous Dunbar Hotel, a popular hangout for the African-American elite in the first half of the 20th century, this 171-unit building now houses mostly low-income seniors paid for by federal Section 8 housing benefits.

Longtime residents apparently watched the new skyline popping up around them with growing dread, knowing that their building would make a juicy target for the kinds of developers who are not above kicking hundreds of pensioners to the curb to make a buck. As expected, the building was put up for sale in 2008.

Then something strange happened: with the help of outside financing and legal advice, the tenants exercised their rights under D.C. law to buy the building from their landlord. Where did a bunch of low-income retirees get $26 million? From one of the developers that wanted to buy the building, naturally.

City Paper was typically skeptical of the deal, but other outlets painted it as a victory for the seniors who would become homeowners for the first time. However, that’s not exactly true: the developer who financed the deal, Jair Lynch, “will maintain a 99.9 percent ownership interest in the project” according to documents reviewed by the City Paper. The remaining 1/10 of one percent (0.01%) ownership share would be split evenly between the residents’ association and Jair Lynch’s holding company.

The developer insists that keeping the Section 8 tenants on board was part of the plan all along — possibly for the associated tax breaks, as City Paper speculates — though it seems unlikely the building will be accepting any new low-income rentals once the current residents pass away or otherwise move on.

In any case, the old Campbell Heights apartments are indeed gone. The building was renamed after poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, namesake of the former hotel and the first African-American poet to gain national acceptance in the US.

14. The Fourteenth Station: Saint Augustine Roman Catholic Church

Standing there at the back of the packed church during Easter Sunday services the other weekend, I was struck by something about the people around me. I’ve always considered my neighborhood “diverse” because when I walk down the street I pass by all kinds of people of different races and ethnicities, speaking different languages, wearing different clothes, doing different things. But that’s all I do: pass by. Usually to some bar or restaurant where I’ll be surrounded by people exactly like me.

Saint Augustine’s sweaty, standing-room-only Easter Sunday service represented the most diverse group of people from the U Street area I’d ever seen under the same roof, doing the same thing. And I mean diverse not only in the sense of race, but also age, class, and length of time they’ve been in the neighborhood: recent immigrants and incoming gentrifiers are just as welcome as those who have been in the neighborhood for decades or generations. After all, that Polish guy may not have enjoyed the choice of Easter Sunday music, but he didn’t hate it enough to keep walking towards one of the whiter churches a few blocks away, either.

Researching this story, I didn’t find God, but I did find out a lot about my neighborhood — my home — and the important and often unsung role of religious organizations in stitching it together. There’s plenty to complain about when it comes to the Catholic Church as a global organization, but I’m happy to keep going to Saint Augustine’s now and again to spend an hour with neighbors I would never see in any of my other U Street haunts. If not for the spiritual uplift than at least to enjoy the jazz.

Jon Custer lives and works in Washington, D.C.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments