How to Be Rich And Fabulous in Florida, According to the Cement Butt Nurse (Alleged)

by mitchell sunderland

Last November my mother called from Florida to discuss her favorite topic: Dottie, her on-again-off again housekeeper/best friend she’s employed for twenty years. “I don’t know what’s going on,” she said. “Dottie keeps asking for pay day advances.” Twelve-hundred miles away in New York City, I told her I’d solve the mystery when I came home for two weeks at Christmas — the maximum amount of time I could handle in the sunshine state. I didn’t give Mom’s problem with Dottie any thought. A new problem would have emerged, by the time I arrived home — it always did.

But when I walked into our house on Christmas Eve, everything was fine. Dottie looked like a tourist who won the lotto on a hot summer day. “I got a big check coming,” she said as she decorated the Christmas tree. “I’m getting five grand in tax returns!” This, I knew, was impossible. She worked part time in 2011, making approximately $300 a week for six months, a grand total of $7,800 — only $2,800 more than her supposed tax return. I asked her how she figured. “I found a miracle worker,” she said. “All my neighbors in Carver Ranches use him. He has a white Bentley and promised me I’d have my money in two weeks.”

Instead, the IRS called. Her check had been mailed to an address in Georgia. Fearing fraud, Dottie went to her accountant’s office. A line wrapped around the small blue and white shopping plaza where C&K Tax Consultants was housed. A sign said, “back in 15 minutes.” Other people were waiting, too — but the accountant never showed up.

“He fucked over the whole hood,” Dottie said. “They’re gonna kill him if they find him.” As rumors spread that he had fled to Georgia, the community increased their search.

They found him on a talk show.

It was late January when Corey Eubanks appeared on The Cristina Show, the Maury of Latino TV. He was there to answer to a woman named Shaquanda’s claims that Corey had acted as a broker for Duchess, an infamous drag queen accused of performing illegal plastic surgeries. Shaquanda claimed that Duchess injected her butt with cement and fix-a-flat instead of silicon, and that Corey was an accomplice.

In the Cristina clip, Corey is wearing a shiny black shirt and white pants that could be described as ‘Liza Minnelli chic.’ “You lie!” Corey screams. “My decision to let you use my house shouldn’t make me go to jail!” While Corey and Shaquanda yell at each other, Brunetta, Shaquanda’s mother, approaches the stage from the audience, picks up a prop syringe from the stage’s table, and as security surrounds her, flings the syringe directly at Corey’s face. The clip, of course, went viral.

It was my mom who called to tell me that Dottie’s tax consultant and the cement butt nurse were the same person. I’d heard about this classic Florida tale already — pictures of Duchess had graced Gawker months earlier, and Corey’s clip had shown up with lightning speed. Hearing that the “cement butt nurse” and Dottie’s accountant were the same guy, I felt Florida’s allure all over again. I was two degrees away from the cement butt nurse! The situation was ridiculous, campy, Dickensian, operatic. It was also real life. In the midst of a cold, boring, New York February, the thrill of an endless summer appealed to me again. I bought a ticket to fly home and find Corey. He was a fellow Floridian. I wanted to hear his take.

Throughout high school I promised myself that once I turned eighteen I would leave Florida and never look back. I was raised on watching people self-destruct, from drugs, from sex, from spending all their money, from resorting to crime in attempts to get more. But why did all my friends and family stay behind, letting the unhealthy cycle continue to happen every weekend for the rest of their lives? Why did I see destruction that never ends where every other local saw an endless summer? What was it about Florida that made the impossible task of “making it” seem possible?

In Corey Eubanks I would find my answer, or at least an answer. Tracking him down proved difficult. Corey’s friends are his customers, and his customers eventually received their checks from the IRS. Nobody would talk.

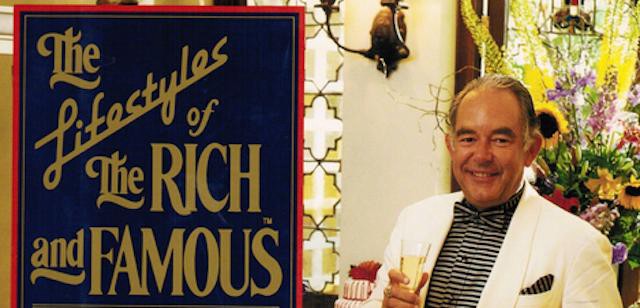

So I drove for two hours on Coconut Creek Parkway to find Emilio’s Latin Cafe, a restaurant and bar where Corey hosts a singing competition. (In addition to his tax consultant business, Corey is also a personal trainer, image consultant, and “reality TV radio blog talk show host & producer.” He also owns a clothing boutique.) The restaurant is in a strip mall, hidden behind a CVS, illuminated only by yellow streetlights. There may be Hummers in the parking lot, but Emilio’s is an underworld.

A huge man in a beige suit with a row of gold teeth guarded the door. Speaking in a quiet voice, he tried to coerce me into entering the restaurant. “You like to party?” he asked. “No age for drinking. We got food. No age for drinking. You like chicken wings?”

The door fee was $15. Performers paid $20 for the privilege of performing and the chance to win $100 and, evenutally, the grand prize, $1,000. Only one act performed that night, two rappers. They wore designer Polos and expensive sneakers, and after their performance, they celebrated their success in front of a stranger’s cheap nineties video camera. Their excitement was palpable, but their failure was imminent. Corey had duped the performers into thinking that somehow, from this dive, he could bring them up and make them stars. I went for a walk. When I came back, two men in Easter egg colored suits stood next to a white Bentley; Corey sat in the front seat.

“Is this closed?” I asked.

“Come back in a week!” the driver shouted.

“Can’t. Live in New York.”

“What are you doing here?”

I walked to the car and recognized Corey instantly. A green pastel shirt hugged his muscles; hairless cheek lines defined his symmetrical dimples. Without women screaming accusations at him, his beauty was obvious. This forty-year old man was ageless.

He pouted his lips and looked up at me. “How did you hear about this?” he asked.

“You’re all over the internet,” I said. “I want to interview you about your businesses. How are you so successful?”

“Do you believe in ‘The Secret’?” Corey asked. He ran his hair through his waist length braids.

“Sort of.”

“So you don’t believe in ‘The Secret.’” He sat back and smiled. Like Scarface clutching a gun or Judy Garland performing at Carnegie Hall, he skirted the line between erratic and controlled. “You know what the difference between us and you people in New York? You go to work. You get on the subway. Then you go to the club. You never socialize. In Florida, we drive. We talk. We socialize.”

Corey’s entourage nodded in agreement. “There’s that song. What’s the song?” Corey asked. He scanned through his iPhone for several minutes.

“I don’t need to hear the song,” I said.

Silence. Corey looked up and grimaced. “Well … I want to listen to it!!!”

He found the song, attached his iPhone to the Bentley’s stereo and then pressed play. It was “Take Time” by Ledisi. Eyes closed with arms in the air, he sang a duet with his stereo. Against the yellow streetlights his braids glowed.

“Though sometimes it seems / everything is wrong,” he sung. “Endless hours / you’re working so hard in your fancy suit / exchanging business cards.” He looked at me. “Ooh, you wanna find a place to escape /It’s your life /You gotta do whatever it takes.”

Corey turned off the stereo. As he looked at me I thought, He’s perfect. He’s everything that’s amazing about Florida. He made me think only of warm weather and cold screwdriver vodkas, the permanent summer I abandoned for cold, bitchy New York. God, I thought. I’m a fucking idiot. I could have lived in a hotel. Instead I’m in a dorm room.

Corey got out of the car to give me his cell phone number. When he turned around, I noticed he had an oval shaped butt that protruded from his pants. Corey’s butt looked like solid rock.

I met Corey the next day at Starbucks. He wore black Chanel sunglasses, a black tee, and plaid shorts over tights, which barely covered the tattoo crawling down his leg. In another state his appearance at a Starbucks in the same shopping plaza as Pottery Barn would seem odd, but here he fit right in with the housewives living off credit cards. They had matching Chanel glasses and matching mochas.

Corey was happy to discuss his lavish lifestyle. He grew up middle class during the 1980s cocaine wars that transformed Florida from a vacation state to a region known for gaudy lifestyles, the butt of a joke. Although Corey’s single mother bounced from job to job, she made sure her children only wore designer clothes — regardless of the price. Corey mentioned “the hood” several times, yet he insisted that he was middle class. To him, class was based on mindset, appearance, and material belongings rather than census data. Yet he also knew that everything in life has a price.

“My Mom taught me I could do whatever I wanted, but that I had to work hard,” Corey said.

He went to college at Southern University in Louisiana, but after three months he dropped out and moved in with his mother, who had recently moved from Pompano Beach to Hollywood, Fla. He never said what prompted his return home. Twenty-one years old and living in his mother’s house, Corey saw his prospects in Florida dim toward the discount side of the shopping plaza.

“I wanted to be a boss,” Corey said. He started several businesses, but his startups failed. He first owned a photo store (“Photos don’t make money”); then a hair salon (“Hair is fickle, you have to keep up with new hairdos”); and then a shoe store (“Terrible idea; if you have a shore store in the hood, everybody wants a discount”).

Corey brushed off any question regarding how he funded his businesses. Although he refrained from explaining his infrastructure, he bragged about his results and philosophy. Fifteen years after starting his first enterprise, he found success as a tax consultant. After his boss at a tax consultant firm taught him tax tricks, Corey parted ways and opened C&K Tax Consultants. The company files taxes and sells insurance and related products. Corey claims his associates can erase eight items from a bad credit report in thirty days. He prepares his clients’ taxes himself.

Corey had no issue disclosing the marketing secret at the heart of his business’s operating philosophy: He caters to friends and family. “I help them make their own money,” he said. “I go to my family first and friends second.” I told Corey that I’d assumed he’d relied on gay clubs to keep his social life and business alive, but he laughed at this idea. Corey diagnosed one of Florida’s problems. “The gay scene,” he said. “The gay scene ruins lives.”

It tangentially ruined his, though I don’t think you could blame Corey’s current woes on a specific person. But yes, it was a gay club where Corey first met Duchess. She wore shiny clothes and chatted with everyone she passed. “Call me Duchess,” she said. Nobody questioned her title or origins. Even the high rolling customers accepted Duchess as a deity because she acted like one.

Two years ago Duchess’s butt wasn’t an internet famous, table sized monstrosity. “Back in the day, his body was perfect,” Corey said. “His waist was small but his butt went out a little. Didn’t have too much face or work done. She was the most beautiful boy or girl you’ve ever seen. You would have wanted to be him.” (Although Duchess identifies as a woman and goes by female pronouns, Corey repeatedly referred to her as “he.”) The gossip that swirled when she left the room suggested Duchess shaped her body, the most beautiful body in the state, with her own hands.

I never heard about Duchess when I lived in Florida. In vacation towns, the gay world is split between tourist traps and local spots that you just won’t find when you’re a horny teenager googling “gay nightclubs 33021.” Internet searches cater to tourists. You have to know someone who knows someone who knows someone that will tell you about Trixie’s Tranny Emporium, a shack-sized transsexual club off Dixie Highway, or Club Boi, a club where Corey occasionally takes friends.

These bars are a close-knit community. Duchess became known among the gay scene as a cheap plastic surgery hookup. People knew Duchess lacked medical training, but her body was visual proof that the surgeries were harmless; she practiced the surgeries on her own body. Despite Corey’s alleged millions, he paid Duchess $700 for a butt lift. “She cut it open,” Corey said, standing up to mime slicing his upper buttocks. “She lifted it a little.”

Corey and his friends laughed at the idea that the procedure was unsafe. “Lot of underground doctors in the hood,” he said. Corey grew up around these surgeries; impoverished people used them so they could look like beautiful millionaires.

“Everybody got a booty. World got a booty. Look at my Facebook friends.” I looked. Although most his friends could fit in medium-sized shirts, their butts would require two airplane seats.

As Corey’s tax business promises customers huge returns, Duchess’s low-cost butt surgeries promised glamour for all. If the product looked beautiful, if it sounds cheap, why should Corey doubt underground surgeons? “Everybody asked me for Duchess’s number,” he said.

One such everybody was Brunetta, the woman who would later throw a prop syringe at him on a daytime talk show. Corey claims he simply gave Brunetta and her daughter, Shquanda, Duchess’s number; the women claim that he acted as her nurse and booker. “She begged me for Duchess’s number,” he says. Eventually he gave it to her. “If you ask me for the weed man’s number, and I give it to you, and then the weed man laces your weed with PCP, that ain’t my fault,” he said. “That’s the weed man’s fault. It’s the same thing.”

A year later, cops interrogated Corey about his involvement in the case. He pled the fifth and then bought a Bentley.

On November 23, 2011, state authorities arrested Corey for assisting Duchess. Police told local news that Corey shared Duchess’s profit and escorted patients from Duchess’s home. Multiple media outlets portrayed him as Duchess’s nurse.

“It was crazy,” Corey said. “I couldn’t believe it.” In the midst of his new success, the middle class boy who longed to be boss forgot that everything comes at a price. Corey let new money blind him. Corey thought every butt surgery was a good butt surgery. Nothing could go wrong. But his vacation was finally ending, and he lacked sympathy for his alleged victims: “They’re life ruiners,” he told me. Their own, and his.

Corey hired Lionel Tate’s former attorney, Jim Lewis, to represent him. After producers pitched the idea, Lewis advised Corey to speak out on The Cristina Show to defend himself and save his reputation.

I wanted to understand the larger picture of the cement butt saga. I reached out to Duchess, to Brunetta (who now faces criminal charges for injuring Corey), and to Rajee, another alleged victim who is now running for president as “President Cement Face.” But nobody answered my messages. I called criminologists, sociologists, psychologists — no one would return my calls. The one professional that would give me an opinion about the scandal was Ariel, a stripper who recently left Florida for Los Angeles. “The cement butt thing happened in Florida because people let it happen. You think that would happen in LA?” she said. “In Florida we’re like, ‘We want to be glamorous, and we don’t give a fuck.’” She doubts the hoopla will serve as a cautionary tale.

Corey’s story is a cautionary tale against shortcuts to glamour, wealth, and beauty, but Ariel doubts people in Florida will take heed. I doubt it, too. Even Corey doesn’t seem particularly moved by his own woes. He genuinely believed that the underground surgeries were harmless and that recommending friends to Duchess was charity. Even now, waiting for trial, he continues his efforts to help fellow Floridians have fuller lives. His Twitter is a bastion of self-help and positive thinking. On Tuesday nights at C&K Tax Consultants, Corey pays it forward by hosting free ‘Millionaire Mixers.’ “People are taught you have to wait to have nice things,” Corey said. “That you have to save up to have a car and house. People don’t know you can buy a house without putting down any payment.”

I pointed out that many homeowners who never paid a down payment lost their homes, giving Florida the nation’s second highest foreclosure rate. Corey laughed. He had a house foreclosed on, and look at him. (He bought a house in 2008 for $500,000 and spent thousands decorating the living room. Two years later it was only worth $100,000. The house was foreclosed on, and Corey moved to a different house.) That isn’t to say Corey doesn’t consider himself a millionaire. He drives a Bentley and wears Chanel. He looks like a millionaire. Therefore, he is one.

And that’s Florida. There’s always someone in a charlatan’s white suit and a Bentley claiming to be a millionaire, and people lined up around the block to listen and hope on every word.

Mitchell Sunderland is freelance writer and digital copywriter in New York. His work has appeared in VICE, Rookie, Emily Books Quarterly, Huffington Post, and Thought Catalog. He tweets and tumblrs regularly.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments