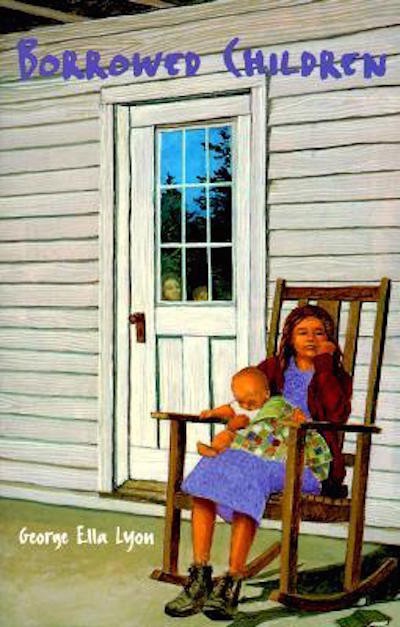

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: George Ella Lyon’s ‘Borrowed Children’

This book is about family. In some really weird ways.

I hadn’t read Borrowed Children before; it was a recommendation from Billfolder rmybrat, and it tells the story of the Perritt family, living in rural Kentucky during the Depression.

12-year-old Amanda—which was a very uncommon name during the early decades of the 20th century, as Baby Name Wizard notes, but a very popular name in 1988, when this book was published—just wants to go to school and use her education to get out of her stifling small town.

“Money is already a problem around here,” Amanda narrates. “Sawmill business is down because of something called the Depression, and Mama is expecting another baby. Don’t ask me why. A baby is the last thing we need.”

When Mama’s baby arrives, Amanda is forced to quit school so she can care for the newborn infant—as well as her parents, her two older brothers, and her two younger sisters—while her mother heals from a traumatic labor and delivery.

Then, when Mama is well enough to take over the household work, she announces that Amanda is going on a surprise trip to Memphis, to visit her relatives.

Amanda had hoped to be able to go back to school, but a surprise trip to Memphis doesn’t come every day, and she is excited to visit her grandparents and spend time with her mother’s sister Laura, whom Amanda admires because Laura has a wealthy husband and no children. Amanda, from the very beginning of the story, is adamant that she will never become a mother—and weeks of caring for an infant and cooking for an eight-person family have only strengthened her resolve.

But, as the chapters progress and Amanda discovers the pleasures of bathing in water that hasn’t already been used by four or five people, and eating as much as she wants without having to leave all of the second helpings for her father and brothers, you get the sinking feeling that this story isn’t going to be about getting out of poverty in rural Kentucky, or about choosing a life outside of what is expected for young women.

This story is going to be about family.

It’s going to be about family in some really weird ways, because we learn that Laura is an alcoholic and that Amanda’s grandmother believes that all of Laura’s problems could be solved if she would just “soften towards a child.” Her grandmother specifically tells Amanda that she “used her” to get Laura more excited about the idea of parenthood. (Laura reacts to this by increasing her drinking. This is in the text.)

Amanda’s grandmother isn’t the only one using her to accomplish another goal. We learn that Amanda’s mother sent her to Memphis to break the bond between Amanda and her infant brother. Seriously. When Amanda’s mother was Amanda’s age, she had to take care of Laura while her own mother recovered (from the grief of her oldest son’s death), and Laura loved her big sister more than she loved her mother, and so now Amanda has to leave the family so her infant brother won’t love her best.

Lastly, we learn that Amanda’s grandmother would have been more than happy to come out to Kentucky and help the family when they needed it. She is appalled that they pulled Amanda out of school: “I would have come, child. I could have taken care of her and that baby, too.”

But, after all of this, after being used by every adult in her life except Laura, Amanda is still homesick and she still chooses home. She couldn’t not choose it, really. Not in this kind of story.

But what does Borrowed Children have to say about money? We learn that the Perritt family is keeping themselves afloat by abusing credit; Mama orders an emerald ring from a jeweler in Memphis, receives the ring, uses the ring to secure a loan, and then sends the ring back to the jeweler so she doesn’t have to pay for it. (I have all kinds of questions about this, starting with “what happens if they can’t repay the loan and the lender asks for the ring?”)

We also learn that the Perritts are writing bad checks and dodging creditors. We learn that the two oldest boys are sneaking out to eat in hotels and charging their meals to a tab they don’t plan to pay. The hotel thing becomes understandable when you read Amanda’s description of her family’s meals, which include hard biscuits and dry meat. (And she still can’t ask for second helpings, because the men need it more than she does.)

At the beginning of the story Amanda explains that she’s always fantasized about being adopted; that she doesn’t want to belong to these people. At the end of the book she’s decided that she does belong.

I’m still rooting for her to get out of this situation—especially before the check kiting catches up to her parents—and build a life of her own.

I am probably more critical of this book than I would have been had I first read the story as a child. It reminded me a lot of Paul Fleischman’s The Borning Room, another story about a young girl in rural America figuring out where she fits into family and motherhood—and I remember loving that book, although I haven’t re-read it in years.

So, to rmybrat and other Billfolders who have also read Borrowed Children: what did you think of the story? Did I misread what’s really going on here? Or is this an accurate summary?

Previously:

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: ‘The Return of the Great Brain’

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments