One Little Way The Tax Code Sucks For Student Loan Borrowers

The Small But Important Way Student Loan Borrowers Get Dinged on Taxes

Hello, it’s me again, the girl who writes about student debt! And I’m here with an article I’ve been meaning to write about for years but that I keep forgetting because I tend to block out the misery that is tax season almost exactly as soon as I’ve cut yet another big check to Uncle Sam.

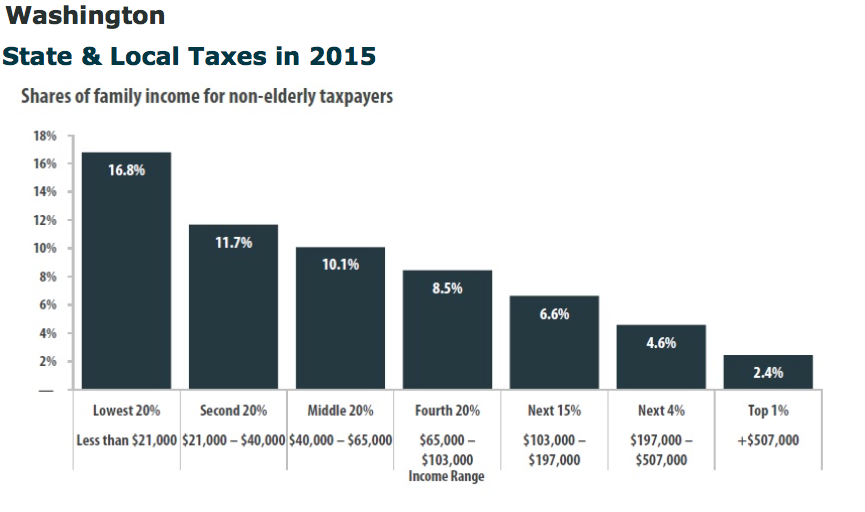

This is not because I am a person who hates taxes. I do not. I actually quite like taxes: they pay for education and roads and social safety nets and all kinds of other important things. Though I wish our tax burden, especially in my home state, were placed less on the backs of the poor and more squarely in the hands of the extremely wealthy.

What I do not like is when the parts of the tax system could be used to benefit people and are not. Which is the case the interest paid on student loans and the relatively meager credit available to recoup it.

Here is the thing about student loan interest: it’s shitty. It essentially means that poor kids, and even not-so-poor kids, since most students take out some kind of debt and almost 7 million Americans currently owe money for college, end up paying way more for college as kids whose parents had some or all of the money for school up front.

How much more? Great question! Let’s do some math.

The average cost of college, according to the College Board, is about $24,061 per year for a public, in-state college. That includes tuition, room and board, books, and other supplies. That would mean a four-year degree would cost about $96,244. Holy hell.

Just to eliminate all the “work hard and save money!” hindsighting that people love to get into, let’s say that your student is working enough to support themself, pay rent, and buy books. They’re literally just taking out enough money to pay for tuition, which, for the record, is what I did. Tuition for an in-state, public university is about $9,139. That means the grand total of the loan required would be $36,556.

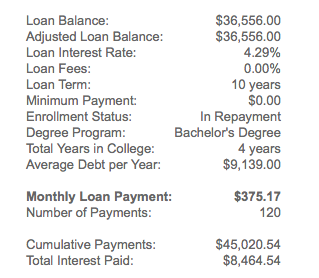

Ok, we can work with that. Let’s also say that all of the loans are at the same interest rate, which we’ll put at 4.29%, since that is what the current Federal rate is.

Now, let’s say your student graduates, gets a job (somehow!) in that six month grace period, and is ready to start paying off that debt. How much will they end up paying if, say, they pay it off in 10 years? (That is unlikely, but we’ll be optimistic.)

In total, your student will pay about $8,464.54 in interest over the course of ten years, or just less than one extra year of college. Which is … ok. That’s feasible.

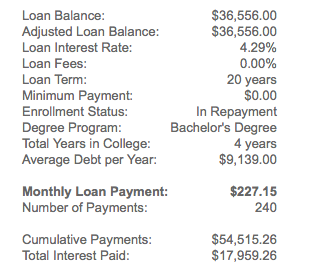

However, research has shown that it actually takes people about twice that long to pay back their debt. So it’s back to our calculator to assume that your student will pay off their debt at 42 instead of 32.

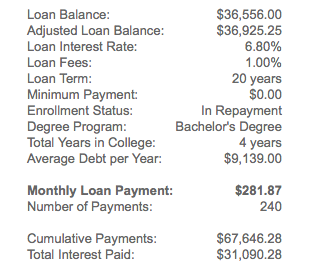

Oh. Well. Now your student has paid 149% of their original debt. The total interest they’ve paid could have purchased more than half a degree. And that’s with a pretty low interest rate; lots of us are paying 6.8% on some loans, as that is the Stafford Loan rate.

Your student has paid 149% of their original debt. The total interest they’ve paid could have purchased more than half a degree.

Just for funsies, let’s see what that looks like.

Congratulations! You’ve just purchased most of a Tesla! Oh, no, wait. You didn’t. You paid twice as much for your degree in interest as you did for tuition. That’s how that went.

All of which is to say that you can end up spending a lot just paying back your student debt. Which is fine—we’re all pretty used to paying interest on things like our credit cards and our home loans.

However, mortgages and student loans have one huge difference: a mortgage is incentivized through the current tax code, while a student loan is not so much.

Now, it’s not as if student loan borrowers truly get nothing in this transaction; you can deduct a portion of the interest paid on your student debts, provided you make under $80,000 as a single person or $160,00 for a couple filing jointly. Which sounds like a lot—it’s more than the annual median income by quite a bit—but is not enough to qualify for most of the tax benefits that help the super-rich. It’s also not enough to buy a house in many major cities where college graduates might want to live/where they might be able to get a good job, including Boston, DC, New York, and San Francisco, which means the income level where the credit falls off is actually not even quite a middle-class wage.

And you can only deduct up to $2,500 per year, or about $208.33 of your student loan payments per month. If you owe no taxes, you can get 40% of the credit ($1000) back.

But of course, because student loan interest can be such a bear, a lot of people pay just barely into the principal on their accounts each month, ensuring that they’re paying much more than $2,500 per year in interest, and only getting some of it back.

That’s compared to a mortgage, where you can write off the first million dollars paid per year and there’s no income cap.

The upsetting thing is that this is actually an expanded tax credit, and one that the White House and President Obama were really excited about. Initially set to expire in 2012, the credit—called the American Opportunity Tax Credit, which expands the Hope Credit—has been extended through 2017.

It’s not enough. And it could easily be fixed by lifting the income cap and increasing the amount of interest a person can write off.

When you offer a tax credit, you necessarily take money back out of the tax base and put it into a person’s pocket. But it’s important to look at where the money goes and what is done with it. Tax credits for corporations, tax credits for second homes (YUP, THAT’S REAL), and the low / non-existent capital gains taxes are draining much more money from the economy on behalf of people who can readily afford it.

Meanwhile, the difference between $2,500 and $3,500 is small for the government, but huge for a person who only makes $30,000.

Student loans are drag on the economy. When people are in debt, they are less able to buy stuff, hire people, and do things that help cash flow freely. When so many student loan holders are already delinquent, are already so behind, and when the government itself already owes so much, it seems ridiculous to nickel and dime people for going to college, while continuing to offer huge tax breaks for people who wouldn’t even feel it if you took them away.

As politicians and activists are wringing their hands and trying to chip away at the cost of college, there are some sweeping solutions—Bernie Sanders wants to make it free—and lots of little things.

This tax credit is one of those little things, but it could make a huge impact in the lives of people who are trying to do the right thing.

This isn’t the solution to student debt. But, with the credit set to expire next year, now is a good time to write your legislator and let them know that this one little thing could actually make a real difference in a real issue that everyone is really concerned about.

Hanna Brooks Olsen is a writer living in Seattle. She can be found on Twitter at @mshannabrooks.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments