Library Guilt

What’s the responsibility of those in the field to use our meager earnings to support the field?

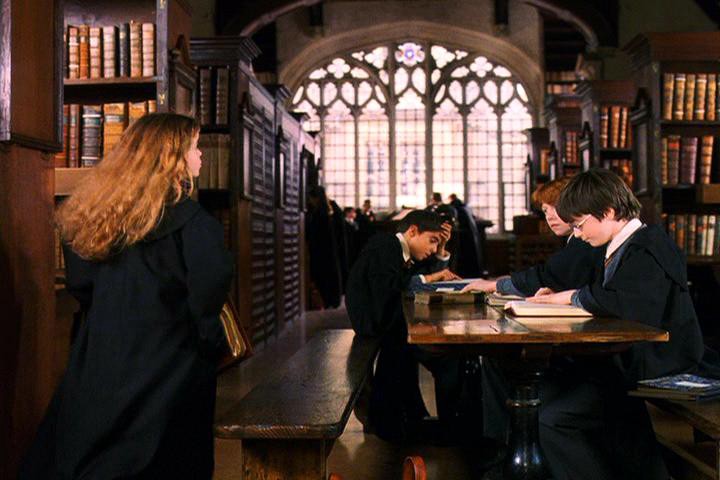

Nicole’s goal to purchase more books in 2016 got me thinking about how few books I buy relative to how many I read. Especially given this comment by Ravenclawed:

Books come to me as ARCs from sales reps, from my editors at B&N, from the giveaway shelves at the Awl office; they come on loan from friends and as gifts from relatives; they come to my nightstand and my e-reader via the library. Of course I patronize my local independent bookstores! Just … usually to get presents for other people.

What was the last novel I paid money for and kept? I’m drawing a blank.

This isn’t good. If people like me don’t spend $30 on a hardback, who will? On the other hand, the world sure makes it easy for people like me to keep up with the latest in literary fiction without ever spending a dime.

Part of my mandate is to encourage other people to buy books, and hopefully I’m at least semi-successful at that. Even if all I did was patronize libraries, though, would that be bad? At least one author thinks so. He has risked public condemnation to declare publicly that yes, libraries deprive authors of their financial due.

Deary claims that free, government-subsidized libraries “have had their day” and drain both public coffers and authors’ royalty checks. According to Deary, public libraries do nothing to help the book industry and are a waste of government resources.

“We’ve got this idea that we’ve got an entitlement to read books for free, at the expense of authors, publishers, and council taxpayers. This is not the Victorian age, when we wanted to allow the impoverished access to literature. We pay for compulsory schooling to do that,” Deary said.

Libraries don’t exist to “help the book industry”; they exist to help people. And society as a whole benefits from having a better educated, more well-read population. Still, it’s true that, at least in the United States, libraries don’t seem to do too much for writers. A library pays once per copy of each book, no matter how many times it goes on to loan out that copy.

That model is not the only possible one. In the United Kingdom and Ireland, authors get additional payments when their books are borrowed.

Under the PLR system in the UK, payment is made from government funds to authors, illustrators and other contributors whose books are borrowed from public libraries. Payments are made annually on the basis of loans data collected from a sample of public libraries in the UK. The Irish Public Lending Remuneration (PLR) system covers all libraries in the Republic of Ireland and operates in a similar way.

A popularity bonus! And why not? Well, because plenty of local libraries in the US have a hard enough time staying open as is. One Pew poll from 2015 showed that “Americans are divided when it comes to the role of public libraries,” with lots of respondents shrugging off the idea that they would be adversely affected by closures.

Those respondents should maybe listen to John Green, who argues that libraries actually do a lot for writers and readers alike:

The truth is you can’t get “anything” via piracy; there are hundreds of thousands of books you can’t get, because they aren’t yet popular. American public and school libraries play a huge role in preserving the breadth of American literature by collecting and sharing books that are excellent but may not be written by YouTubers with large bulit-in audiences.

Libraries improve the quality of discourse in their communities in ways that piracy simply does not. And if it weren’t for the broad but carefully curated collection practices of libraries, the world of American literature would look a lot like the world of American film: Instead of hundreds of books being published every week, there would be four or five.

He also points out that libraries do often end up buying more than one copy of a book, since paperbacks especially wear out and must be replaced. Academic librarian Kristin Laughtin seconds this argument:

For popular titles, most libraries buy multiple copies to meet demand. Depending on the size of the library system, they might even buy 50 to 100 copies or more of bestselling titles, especially when you count all formats: hardcover, large print, audio CD, and now e-book.

It’s also a necessity for libraries to buy multiple copies, as books wear out quickly, often after 25 check-outs or so. One copy just won’t last for 1,000 uses.

For e-books, chances are libraries aren’t paying the same $10-per-book you would. They have to purchase lending rights, and the fees get higher as more flexibility is added to the license.

OK, I definitely feel less guilty now. Still, even if I have no immediate incentive to do so, I should make more of an effort to support the businesses — and an industry — I value.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments