When Even Small Debts Pose Big Problems

It’s easy to focus on the people who have truly alarming levels of student loan debt. As the New York Times points out, though, “the biggest borrowers tend to become the highest earners.” Those are the eyes-on-the-prize types who took out money to pay for graduate school and are fated for positions as doctors and lawyers; they will pay back what they owe and have plenty left over for vacation homes.

Forty percent of new loans go to graduate students. Among those earning law and medical degrees in 2012, median debt (undergraduate and graduate school) is $141,000 for lawyers and $162,000 for doctors.

Those holding graduate degrees tend to handle higher debt because they earn more. Over the past 50 years, workers with graduate degrees have enjoyed the largest gains of any education group, with their inflation-adjusted earnings nearly doubling since 1964. Some struggle, of course: The Department of Education estimates that 7 percent of graduate borrowers default. But this default rate is far lower than the 22 percent rate for those who borrow only for their undergraduate studies.

I’d wager that a lot of the people who make up that 7 percent who struggle are those who borrowed for humanities PhDs, which are entry passes to the far less stable academic market — especially when the borrowers don’t come from positions of privilege. Exhibit A: this rueful, affecting story of a sociology student originally from Appalachia who calls herself “a Poverty-Class Academic In Training.”

we are all haunted by the threat of “Ph.D Poverty”, or the possibility of becoming bright, well-trained victims of the adjunctification crisis. And many of us know that we can look forward to heavy bills to pay from ballooning student debt, whether or not we are able to get a job matching our qualifications in an increasingly break-neck, competitive market.

She continues to feel the ripple effects of growing up poor, even/especially now that she’s surrounded by folks who are often well-meaning but clueless.

My sister and I still battle powerful guilt for any purchase that is not materially necessary for our survival or basic health — even when we have had the disposable income. The process of paying bills, a generally unpleasant task for any person, is a viscerally fearful task which each month leaves me trembling and taking deep breaths to force a return to calm — even when I can cover each cost. There is always a nagging fear that no matter how careful and organized I’ve been, a bill has been forgotten, or an overdraft has occurred. We avoid most routine medical care, and only seek medical attention when our bodies cannot function, because we are so used to not being able to afford office visits or medication. Experience tells us that it is nearly impossible to get an invoice for medical services in advance of receiving care; it is usually easier to go without and hope for the best. I had my first-ever eye exam at 23 years old, upon discovering my graduate health insurance covered one annual exam. Turns out I need glasses. Might even get them someday.

You should read her story in full. She’ll make you reconsider using the word “broke” unless you really, truly mean it.

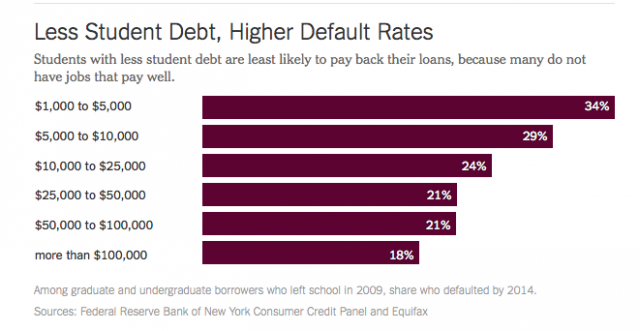

For the most part, though, the students who default or struggle are not those who borrowed to pay for graduate school, or who borrowed six figures at all. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the ones who are in the most trouble are the ones who took out the least.

It’s also interesting to me that people who borrow $25,000 have as great a risk of defaulting as those who borrow $100,000, or four times as much (21% of them, in both cases). But the most sobering fact here has to be that getting a loan of as little as $1,000 can materially affect your future for the worse.

Image from The Debt Project

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments