Publish a Book and Change Your Life, or, Well, Maybe Not

by Christine Sneed

I spent a lot of time in the car this past spring, commuting from my home in Evanston to Urbana, Illinois where I’ve been teaching at the state’s flagship university. During these lengthy trips south, I’ve been thinking about the professional and personal choices that I’ve made since graduating from college in 1993 — a long time ago, I suppose, though it doesn’t really feel like it.

When I decided that I’d try to make a life as a writer during my senior year in college, I set off in dogged, possibly foolhardy pursuit of this goal. It wasn’t so much a conscious decision as a pigheaded, glacially slow march out of complete obscurity, out of the room where I wrote thousands of pages of unpublished work before my first book, a short story collection, was published a couple of months after my thirty-eighth birthday.

If you were an attorney or an accountant and you said to someone, “I’ve been doing this job for two decades and am finally starting to make money at it,” people would look at you like you were crazy.

It’s not a perfect comparison, of course — writers’ skills continue to evolve long past any undergraduate studies completed in the humanities, whereas accountants or attorneys graduate with a skill set that allows them to obtain work before, in some cases, they’ve officially received their diplomas. Their work is also better compensated than most jobs a writer might acquire post-graduation, jobs that often have very little to do with writing. The writing gets done, if it’s done at all, at night and on weekends.

Mine is not an uncommon narrative for a writer’s professional trajectory, but when I allude to these realities in the college fiction-writing classes I teach, I often find myself downplaying the difficulties of my career path. Students want to hear success stories, overnight success stories, if possible, ones where young writers are showered, in short order, with awards and piles of money. They’d like to believe that the books I’ve published, the first appearing in late 2010, eleven and a half years after I finished graduate school, were transferred from my brain to the page into book form without any intervening doubts or difficulties or years and years of waiting and worrying and knuckled-down persistence.

The true circumstances of my life so far, I suspect, would probably seem like a tale of woe to my students, despite the fact it has been one of privilege (even if I might not have the bank account or the property titles to reflect this.) At 43, I’ve never married, nor do I have any kids. I’ve never owned a new car, and two of the three cars that I have owned were purchased from a family member. One was already eight years old, and four years later it’s still, to my relief, the car that I’m driving.

I’ve owned one home, and it’s where I’ve lived for the past eight years, four of them with my domestic partner, Adam. We share a three-room condo, about 650 square feet, on the top floor of a World War I era brick walk-up situated across the street from an elementary school and a Catholic hospital’s emergency room. It is extraordinarily noisy at times. The condo has no amenities to speak of either (something the realtor pointed out when I first viewed this place, but I blithely ignored her) — no dishwasher, no air conditioning, no washer and dryer, no parking. In the summer, in the kitchen/dining/office space where I write, the temperature routinely reaches into the nineties.

Why did you buy that dump? my friends and family ask (especially my father, who put up the lion’s share of the down payment). The darkly comic joke is of course on me. I bought this dump at the height of the market in 2007, desperate, on the verge of my thirty-sixth birthday, no longer to be a renter. The following year, the property lost half its value. Today, it might be worth about three-fifths of what I paid for it, although two years ago when my downstairs neighbor purchased her unit, which has the same floor plan as my condo, she paid a little less than a half of what I paid for mine.

You could say that I have not chosen wisely. And I would admit that it is hard to argue with this assessment, at least if you’re looking at the material facts of my life. I come from a solidly middle class family; my mother is a veterinarian and my father is a retired options trader. I went to Georgetown as an undergraduate and to Indiana University for a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. Aside from room and board, graduate school was nearly free; IU’s MFA students receive tuition remission and a teaching stipend. I had a number of poorly paying part-time jobs in graduate school too (the stipend was only about $800 per month.)

I have no debt though, other than my mortgage. My partner and I are committed, at least for now, to keeping our overhead low. Like me, he earns his living piecemeal by working two part-time jobs because for the last several years, he hasn’t been able to find a full-time position in his career track. Similarly, I haven’t been able to land a tenure-track teaching job. Along with writing fiction and freelance essays and book reviews, I teach as an adjunct fiction instructor or as a visiting assistant professor where I can.

My publisher, Bloomsbury, is an esteemed, mid-size international house with the fine distinction of having taken a chance on an unknown writer back in the nineties, not long after the press opened its doors. This unknown writer is J.K. Rowling. You know the rest of the story. Bloomsbury has been good to me; my editor and her colleagues have put a lot of time and resources into getting my books into the hands of readers.

Obviously, none of this happened overnight. People are surprised when I tell them that I wrote five novels before I managed to publish the sixth, which followed my first book, the story collection, by about two and a half years. Up until I turned 40, I was lucky to earn $35,000 a year working as an adjunct writing instructor at two Chicago universities (I taught four or more classes during some terms; a tenure-track professor usually teaches two or three). I made almost nothing from the stories that I wrote in the off-hours and published in literary journals; often the payment was free copies of the issues my stories appeared in.

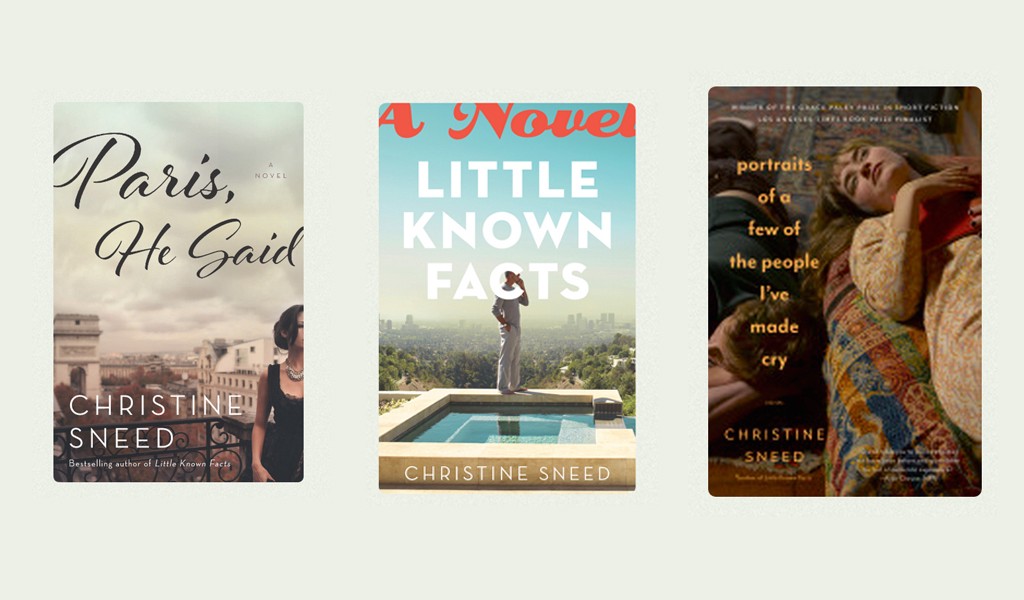

With the publication of my second book, Little Known Facts, lightning seemed to strike. This novel was reviewed on the cover of the New York Times Book Review and went on to receive other good reviews. Not long after Little Known Fact’s publication date, Bloomsbury acquired a second novel and a story collection. The advance for these two manuscripts was $10,000 more than what they paid for Little Known Facts.

The open secret is that literary fiction does not pay big dividends. At least not to most of its writers and publishers. Even with excellent reviews, there’s no guarantee that your book will sell. Little Known Facts had a mid-five-figure advance and it has earned about three-fifths of it back so far. It was reviewed in several major-market newspapers and won a couple of awards. I did readings in cities all over the country to promote it, wrote many guest blog posts, and all told, it has probably sold about 23,000 copies. That figure includes paperback, hardcover, and e-books. Not bad, but by the publishing world’s yardstick, not a standout, not at all.

Occasionally someone close to me will say that I should find another profession and devote less time to writing. I’m not getting any younger, and what will happen when I’m 65 and our government, by that time, has probably removed every social safety net currently in place to help us Americans in our senescent years?

What I stubbornly tell them is that I can’t imagine not being a writer. Maybe this seems a failure of imagination. I know that if I needed a steadier and better income, I’d be better off going back to school and becoming a doctor or accountant. When people ask me if they should become writers, I tell them yes, if the experience of writing — all by itself — brings them joy. Because that’s the only way they’ll reliably find it. The prizes, the bestsellers, the film rights sales — those are dreams. Sometimes they come true, but there is no guarantee.

Christine Sneed is the author most recently of the novel Paris, He Said. She teaches for the graduate writing programs of Northwestern University and the University of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments