The Punishment For Defaulting On Student Loans Is Harsher Than You Imagined

Various states — at least 22 of them, currently — have decided to put the fear of god in their young workers. Jobs With Justice explains:

In Alaska, California, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, New Jersey, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia and Washington, nurses and health-care professionals can all be locked out from their job if they fall into default on their student loans.

In Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Montana, New Jersey, North Dakota, Oklahoma and Tennessee, laws prevent K–12 teachers from working until they begin to repay their student loans. …

These state laws target a wide range of professions, including attorneys, physicians and therapists — even barbers make the list. But two professions show up over and over again: nurses and teachers.

Both professions serve a critical role in our communities and are often wildly underpaid. Are we really in a position to be punishing the people we need the most?

That is what you might call a rhetorical question.

In three states, you can also lose your driver’s license. As we’ve learned, not being able to drive can be a serious impediment to getting or keeping a job, so that seems like a boneheaded punishment. It also reeks of the worst kind of paternalism: we disapprove of your choices, young man, so we’re going to take away the car keys. Ugh. When has treating struggling adults like rebellious teenagers ever proven to be a wise choice?

Defaulting is real the way bankruptcy is real. Ordinary people are forced into it by equally ordinary — but still, often, tragic — circumstances. In September, Forbes reported:

For community colleges, 25.8 percent of borrowers have defaulted to date. At for-profit two-year colleges, where borrowing rates are typically higher, it’s 36.3 percent. … At two-year institutions, these rates for the 2011 cohort are startling — 33.8 percent of loans at two-year private nonprofit and public colleges, and nearly half at two-year for-profit schools are expected to default. Across all school types, the Department of Education reported that a little over one in five loans for undergraduate educations will default within two decades.

That’s presumably the reason that one of the most popular, enduring pieces in Billfold history is Anna Moreno’s “I Defaulted On My Student Loans. Here’s What I Did To Get Back On Track” from 2013. Her story is easy to relate to:

At first, it was easy to not think about my loans. I have a hate-hate relationship with debt. I won’t buy things I can’t afford to pay for entirely up front. I don’t have credit cards. I have no personal or consumer debt, so it was easy to ignore my one and only source of debt. My creditors would send bills each month, and I would throw the envelopes away without opening them. Not paying my loans didn’t seem to have any effect on my life at that exact moment. I was sure my credit was ruined, but I had a long-term lease and eschewing credit cards and other forms of personal debt meant I didn’t care much about my credit score. And I still believed that my non-payment was just a temporary blip. I was certain I’d start to pay my loans off soon. I had faith something would turn up.

A year later, she published an update here:

I am proud to say that my student loans have been successfully rehabilitated and I am no longer in default. … It’s incredible to me that the hardest part about this entire process was making that first phone call and facing my poor financial decisions head-on. But everything after was a breeze.

Happy-ish ending! But making those kinds of positive changes, starting with the first phone call, is easier in a climate of support rather than shame. Taking away someone’s driver’s license, or her ability to do her job, is not helpful; it’s kicking a person when she’s down.

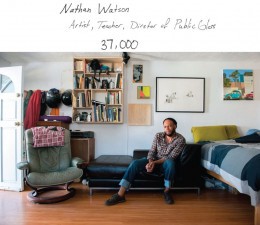

Image from The Debt Project

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments