“When Leon dies, Bard will perhaps die as well”

In this Gawker polemic against Bard college, an expensive liberal arts school author Leah Finnegan attended for two years before transferring to a public university in the South, Finnegan argues that the fates of eccentric, longstanding college president Leon Botstein and the college itself are linked: “When Leon dies, Bard will perhaps die as well.” In other words, she suggests that Bard, like so many non-profits, suffers from Founder’s Syndrome.

Founder’s Syndrome occurs when a single individual or a small group of individuals bring an organization through tough times (a start-up, a growth spurt, a financial collapse, etc.). Often these sorts of situations require a strong passionate personality — someone who can make fast decisions and motivate people to action.Once those rough times are over, however, the decision-making needs of the organization change, requiring mechanisms for shared responsibility and authority. It is when those decision-making mechanisms don’t change, regardless of growth and changes on the program side, that Founder’s Syndrome becomes an issue. We see this most frequently with organizations that have grown from a mom-and-pop operation to a $12 million community powerhouse, while decisions are still made as if the founders are gathered around someone’s living room, desperately trying to hold things together.

Founder’s Syndrome isn’t necessarily about the actual founder of an organization. The central figure could be the person who took over from the founder. It could be someone who took over in a time of crisis, and led the organization to clear waters. Or it could just be someone who has been at the helm forever. The “founder” could be the CEO. Or it could be a board member, or a handful of board members who have either been there since the beginning or have ridden the organization through tough times.

But the main symptom of Founder’s Syndrome is that decisions are not made collectively. Most decisions are simply made by the “founder.” All other parties merely rubber stamp what the founder suggests. There is generally strong resistance to any change in that decision-making, where the Founder might lose his/her total control of the organization. Boards of these organizations usually don’t govern, but instead “approve” what the founder suggests. Planning isn’t done collectively, but by the founder. And plans / ideas that do NOT come from the founder usually don’t go very far.

Partly because Leon “hates money,” Finnegan argues, Leon’s school, despite tuition hikes, is hanging on by a thread.

The school currently survives on Leon’s affectations and the deep pockets of some of his friends, like George Soros. The college has almost no alumni support, because most of its alumni are not wealthy. People don’t go to Bard to become rich. They go there because they didn’t get into Brown, or because they are deluded and sheltered, or because they want to be an artist and make knitted teepees, or because they got a science fellowship (the school does all it can to attract more science students). …

Leon Botstein is no Jamie Dimon, but it’s difficult to defend the mission of a school like Bard, which badly wants creative young people to “invest” $256,000 in its experience, only to wonder why none of those young people turn around to dump their spare coins in their coffers.

I understand Finnegan’s bitterness: as she points out, she is still paying back the loans she took out to finance her two years in playland. But I’m curious how different Bard is from other similar small liberal arts colleges. Students don’t go to Vassar, Hampshire, Bennington, and the like to get rich either, as a general rule. Do their alumni give back after graduation?

(Note: When I began to investigate this, I noticed that when I typed in “Vassar alumni giving,” Google changed the second word to “alumnae.” I corrected that to “alumni” and Google continued to fight with me. GOOGLE, I’M RIGHT. Vassar has been co-ed since 1969.)

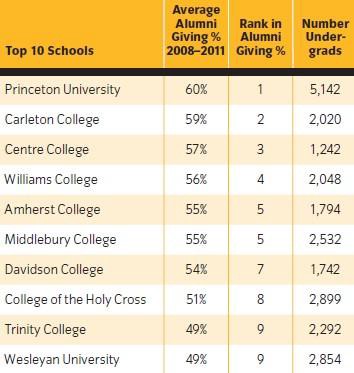

According to Alumni Factor’s compilation of recent information, the top ten schools for alumni giving starts with Princeton, duh, but then gets really liberal artsy real quick.

To me, this says that if Bard isn’t getting money from its alumni, that’s probably because it’s doing something wrong and not because artsy kids don’t eventually give back. Clearly, if they’re fond of their schools, they do. In fact, large universities have a harder time getting their alumni to contribute than small colleges: “there are only three schools within the Top 25 for alumni giving percentage that have more than 3,000 students.” Why? “Small schools with high academic standards and a close-knit community do a better job than larger schools in creating an environment where intellectual development can occur and deep friendships can develop — these two factors appear to have the strongest correlation to alumni giving.”

Maybe students are less likely to donate later when they feel overcharged to begin with, or that their education/experience wasn’t worth the money? FWIW Bard is tied for 45th on the US News “Best Liberal Arts College” list with two other schools and is the most expensive of the three.

Did you think your college experience was worth the cost? Do you give to your alma mater?

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments