Class Consciousness In Kids’ Books

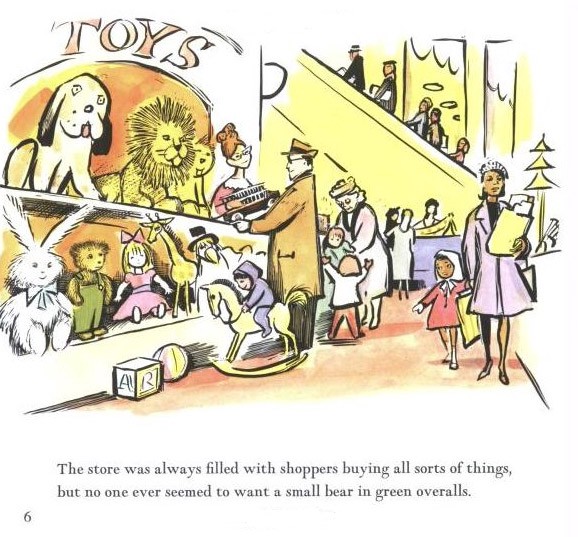

Last night I read the children’s book Corduroy to babygirl for the 15,000th time. A small bear in green overalls wanders a department store at night looking for his lost button, because that button represents everything that is out of his reach: love and acceptance, family, security, home. He is rescued by a girl, Lisa, who believes in his potential so much that she empties out her piggy bank for him. Once she and Corduroy have settled in her bedroom, she sews on a new button for him, not because he needs it but because he’ll be more comfortable with his strap fastened. And then they share a big hug.

Babygirl loves Corduroy. I love it too, partly because it doesn’t elide issues of class and race. When Lisa and her mother first notice Corduroy in the store, they stand out as dark faces against a sea of pink. All of them do, really, as Corduroy is also brown. When Lisa asks her mother to buy the bear, her mother sighs, “Not today, dear. I’ve spent too much already.” #RealTalk! How often does that happen in picture books — or in pop culture in general? The next day, Lisa comes back triumphant to redeem Corduroy with her own savings and brings him up four flights of stairs to her family’s apartment.

“The room was small, nothing like that enormous palace of a department store. ‘This must be home,’ he said.”

In pop culture, poverty is sad, when it’s mentioned at all. Poor, dark-skinned people are never seen as normal, and neither are fourth-floor walk-up apartments. Compare, for example, Corduroy to last year’s Best Picture nominee Her.

Spike Jones’s Her, which is a sort of romantic sci-fi allegory about alienation, glosses over class, race, and commerce altogether. In a city that is supposed to be a near-future Los Angeles, everyone is white or Asian, and no one exchanges money for goods or services, not even the state-of-the-art operating system which is at the heart of the film.

How much would an OS that can think, empathize, anticipate, learn and grow even cost? Especially one that begins as a cross between a life coach and a great servant and ends up functioning as a romantic partner?

We never find out. Our rather emo hero Theodore Twombly obtains the new OS somehow, off-screen, and brings it back to his apartment, which is like that enormous palace of a department store. The OS, a super-intelligent and yet also girly and flirty consciousness, names itself Samantha. It is played by Scarlett Johansson, whose character is the concept of “gender as social construct” taken to a whole new level.

When was the last time ScarJo played human? She’s been a female-identified super-being in several movies now besides Her: The Avengers, Under the Skin, Lucy. This was not always her destiny! ScarJo has appeared normal, even pretend shlumpy in certain films; she got her break playing short, lost, counter-cultural adolescents in Ghost World and Lost in Translation. But directors of late have transformed her into a heartbreaking, terrifying, even lethal, apex of femininity, the counterpoint to the boring feminist idea that “women are people.”

As a smart response to Lucy in the Huffington Post puts it:

what’s sticking in my craw is the assertion that while human life originated in Africa — a detail the film neatly skims over, placing the ape-like Lucy that Johansson sees in North America — somehow the way we imagine the most evolved human being is blonde and white. Even more, when Lucy gets surges of knowledge in the film, her eyes flash brightly blue. Because blue eyes, we all know, are the universal symbol of superiority, right?

Hilariously, as it happens, ScarJo is half-Jewish. But it’s not the Jewish half anyone seems to be interested in these days.

Our society used to be much more comfortable talking about money, or maybe it’s just that the lack of money used to be nothing shameful, a fact of life. All-Americans like Babe Ruth grew up in poverty and, largely, at St. Mary’s, a Catholic orphanage/foster home/school. So did Marilyn Monroe:

Marilyn Monroe was on the cover of the first ever Playboy magazine in 1953. The nude centerfold photo inside was taken by Tom Kelley and was originally for a calendar called “Miss Golden Dreams”. After she became famous, it was discovered that the nude photo in the calendar was Monroe. Rather than payoff a blackmailer at the time, she instead came out and admitted the photo was her stating, “My sin has been no more than I have written, posing for the nude because I desperately needed 50 dollars to get my car out of hock.” Hefner shortly thereafter purchased the right to use the photo in the first edition of Playboy for $500. Besides the initial amount she was paid when the photo was taken, she never saw a dime for it after, even though it made Hefner millions thanks to it instantly propelling his magazine into wide circulation, selling around 54,000 issues within week of that first issue being published.

American sitcoms used to reflect the experience of the working and lower-middle classes as a matter of course. Nowadays the only characters you see struggling on TV are wayward twenty-something white girls. (They’re going to make it after all!)

Television today is more aspirational, and most TV characters have moved up the social ladder. The default class for most scripted shows now is the upper middle class: the world of fancy homes, spacious apartments, nice clothes and good taste. This is a world where no one worries deeply about the next paycheck or doctor bills. This is the world of doctors, lawyers, high-powered executives, unusually talented detectives, entrepreneurs, hipsters, and Presidents of the United States.

Scripted television once depicted a world that generally reflected society (assuming you weren’t black, Hispanic, gay or poor), but now functions mainly as a window into a world that many Americans can only dream about. There aren’t many contemporary TV shows about nurses, plumbers, factory workers or bus drivers. In other words, there aren’t many shows like “The Honeymooners,” “All in the Family,” “Roseanne,” or “Friday Night Lights.” Despite the occasional “Mike and Molly” or “Raising Hope,” viewers seem to prefer watching people who’ve got it made over those still trying to make it.

Hollywood, of course, is no better:

This disconnect was made painfully clear to a set decorator named Rosemary Brandenburg several years ago, when she was working on the set for “Castaway.” Before Tom Hanks gets in that plane crash and has to survive on a desert island, there’s a scene at his girlfriend’s parents house, eating Christmas dinner. “We were asked to make a ‘typical middle class’ dining room/ living room,” Brandenburg remembers. “And I was too shy to go to our director and ask him which middle class he really wanted.” That’s when Brandenburg made her mistake. “I made middle class in my life, which was old fashioned granny lamp shade, print couches and a La-Z-Boy chair, printed wall paper.” In short, a working class version of a “typical middle class home” — well loved, a little bit shabby.

When Rosemary had the set ready, the director came to see. “He walked in and just hated it. Said ‘What have you done here? I mean this looks like grandma’s house!’ He had in mind someone with much more upscale tastes, and up-to-date furnishings. Brandenburg complied with the director’s version of the middle class. She redid the set, lampshade to wallpaper.

Publishing is subject to the same pressures, including herd mentality, as the rest of the entertainment industry. Hence #WeNeedDiverseBooks, which trended earlier this year and became a kind of phenomenon.

Lisa and her mother in Corduroy aren’t POC or cash-conscious as a plot point; they just are. In a world where we’re desperate for all the class and race diversity we can get in our children’s books as well as on the small- and silver-screens, I’m glad and grateful. And while I wait for more high-caliber books that serve the same function, I’ll keep reading it as many times as babygirl requires.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments