It’s So Hard to Say Goodbye to Your First Car

by Eric Nusbaum

The other day, I drove my first car for the last time. It was a short trip, but an oddly pleasant one. I pulled out of a street-side parking space and turned left down an adjacent residential road. There, I executed a three-point turn and brought the car slowly onto the down-turned platform of a flatbed truck. I put the car in neutral, cranked the emergency brake up, and said goodbye.

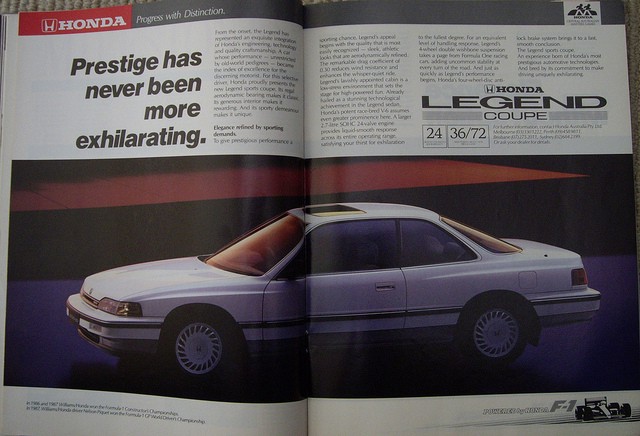

The two-minute drive was the least stressful we’d had together in a long time. For the last year or so, the car regularly convulsed at red lights, trembling slightly, then lurching back and forth. More than once, I had to kill the engine for fear of something exploding underneath the hood. This time, there were no red lights; there was no idling at all. Had I driven even a few additional blocks, it would have overheated. Smoke would have billowed up from underneath the hood, and it would have looked like the car, a 1995 Acura Legend, was running on coal power. But for those two minutes, there was none of that. There was only my car getting me where I needed to go.

When I say I drove my car for the last time, I mean that my car will never be driven again by anybody. It has a blown head gasket. (A head gasket is what prevents coolant and oil from leaking into the engine’s cylinders.) Fluids pouring into the engine have damaged it to the point of no sane return. In other words, the car would be more expensive to repair than it’s actually worth. My mechanic — his shop is actually called My Mechanic — all but refused to fix it. Replacing the gasket itself would cost about $1,500. And that would only be an appetizer to the ensuing main course of engine damage. For context, the Kelley Blue Book Value on the Legend in “fair condition” was $2,781. What about cars in poor condition? “Kelley Blue Book does not provide values for cars that meet this criteria.”

This was a long time coming. In the last two years, I’ve spent about a thousand dollars repairing cylinders, brakes, and other assorted parts. Meanwhile, much has been left in semi-intentional disrepair. The bumper was only about three-fourths attached. The driver-side window hadn’t shut properly since 2007; when I took the car over 40, air would stream in and whistle in my ear. Much of this is typical of Acura Legends, I’ve learned recently. They drive great, but their engines are set in such a way that makes them difficult to access, and costly to repair. Thousands upon thousands of words have been written in online forums about the regularity with which they blow their head gaskets.

I should say that this was typical of Acura Legends. The model no longer exists. Legends were sold in the United States between 1986, the year I was born, and 1995, the year my car was born. Around this time, Acura executives reportedly discovered that the Legend model had better name recognition than the company itself. In 1996, the Legend was rebranded the Acura 3.5RL — the car’s name turning out to be too apt for its own good. The 3.5 of today looks nothing like the Legend from which it evolved, and that’s the way it should be. I took pleasure in driving a car that was no longer made, that despite being an entirely nondescript white, four-door sedan, was also, in its own way, a relic. The name Legend only added to this mystique.

On the inside, the Legend was a luxury car with all the trappings a mid-nineties consumer could want, including a six-cd changer in the trunk. But the six-cd changer hasn’t worked since I was in high school — and it was in the trunk. The lone cup holder quit ejecting from its hiding place in the center console years ago. Hell, at this moment the center console is probably no longer attached to anything. The car has likely already been taken apart, piece by piece, in a salvage yard somewhere on the Olympic Peninsula, a reality that, the more I think about, the more I like. My car will never be anybody else’s. In the back of my head, I think I always knew it would end this way. After all, 11 years ago, this was the car I learned to drive in. Of all the possessions I owned, it was the one I owned the longest.

When I first started writing this, I imagined a sort of comprehensive accounting of all the places my car has driven. It would have started in Los Angeles, ended in Seattle. In between would have been Dixon, Illinois and George, Washington, and Boise City, Oklahoma. But that would have been boring. A car is a car. You might have kissed a girl in it, but you also sat in traffic driving to Santa Monica to get allergy shots. You might have grown to love it, but it was still a pain in the ass, right up to the end.

Even getting rid of the Legend was hard — not emotionally but logistically. The kinds of people who buy broken down cars for a fair price are flaky, lowball you, and miss appointments for three consecutive days — but the kinds who come on time and have 1–800 numbers lowball you even worse, won’t negotiate a dime, and only want to smash them up into scrap metal anyway. I found myself haggling over the phone with guys named Mike and Frankie over a matters of just a few bucks. They’d list off all the parts of the car, and I’d have to be ready to explain, in detail, what was right and wrong about them. I learned more about the Legend in death than I ever did in life. When I finally sold it for $500, I felt like I was mostly just getting paid for the hours it took to finally consummate the deal.

I’m from Southern California. There, a car can be a sort of home in itself. You spend hours in it, often doing nothing. Everything you see is curated by its windows, curated by the roads you take it over. Saying goodbye to a car is like saying goodbye to an entire way of seeing the world. I’ll never sit at precisely that angle again. I’ll never look through a mirror quite the same way. I’ll never drive around for two years with a pair of all-white New Balances, a size too small, molding away in my trunk. I’ll never squeegee the condensation off of the inside of a windshield because so much water has leaked into the car’s frame that the defogger has been rendered useless. On the bus, on the sidewalk, even in my girlfriend’s car, I’m already seeing things differently. I guess that’s how you know it’s over.

Eric Nusbaum lives in Seattle. He writes about sports at Pitchers & Poets and The Classical, and has also written for Deadspin, Slate, and various other publications. His thoughts on Jeopardy contestants and Subway menu items can be found @ericnus, and his clips, etc. can be found at his website. Photo: flickr/fotosleuth

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments