Friends With Venmo

by Amanda Palleschi

We were four exhausted 20- and 30-something women splitting an UberX from Dulles to the heart of Washington, D.C. — a jaunt that will run upwards of $50 under normal fares.

“Can you just Venmo me?” Kelly asked us from the front seat of the sedan.

“I only have PayPal,” Elena said in the backseat.

“Me too,” I said.

“What is that? Is it easy to do?”

We’d just spent a week at the same yoga retreat in Guatemala, but weren’t part of each other’s social orbits back in the city; using a peer-to-peer payment app to split the fare made sense. Part of such an app’s appeal is its ease in these instances. But what followed in the days after the car dropped us off was an email chain 17 missives long as Kelly waited for us all to download the app and find one another on it. It took about as much communicating and momentary confusion as figuring out the bill at a group dinner.

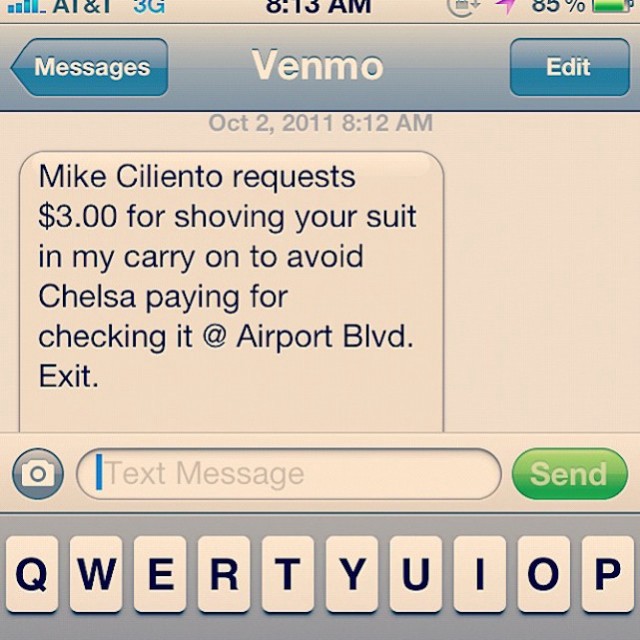

Venmo is most widely used by millennials. Like other topics once known for being verboten at a dinner party, we’re known for being more open than our parents about money. So it’s fitting that Venmo, unlike its predecessor PayPal, includes a social networking aspect: I log in and can see that Alex paid Sara $13 for movie tickets. But we’re also still navigating a time in our lives when careers and financial milestones move at varying paces among peer groups, breeding those awkward bill-splitting moments that so often end in temporary annoyance (“Did you see the way Pat stiffed the bartender on the tip?” “Those girls John brought last night ordered like, three pitchers of margaritas that they didn’t pay for, dude.”)

The explosion of peer-to-peer payment apps (Venmo, once the indie of the payment apps, processed $700 million in mobile payments in the last quarter of 2014) brings with it new, potentially uncomfortable minefields. While the apps have the potential to subvert old taboos about friends and money, are they simply shifting taboos and new comedies of communication errors onto smartphones?

A recent Bloomberg Businesswork story explains that the Manhattan-based startup could be a game-changer for retail and card reading businesses, and its use is spreading beyond large coastal cities. Venmo, and even big companies like Apple, are getting in on the peer-to-peer payment game. Ebay, which now owns Venmo and PayPal, is preparing to take the company public and charge merchants and other new startups to use the service in order to generate revenue.

But could it change the friends-and-money game, too? Venmo is still in its infancy, at least as far as establishing etiquette is concerned. Elaine Swann, a New York Times-annointed “Emily Post of the Digital Age,” sees the potential for conflict in the confluence of money, friends and an oversharing internet culture.

“You have to be careful when you take money, which can cause a huge chasm between individuals and friendship and then the whole false sense of strength that we have because we’re online — that really can be very dangerous,” Swann tells me.

I’m not sure I see the “danger” in such apps, but I’m certainly a skeptic. It started months before the cab ride, when my friend David peer pressured me into downloading PayPal so he could pay me back for $11 beers at baseball games. I was mildly annoyed. I would have gladly let weeks or months pass before David had $11 in cash on hand to pay me back or, better yet, get my beers next time. Now I had to log in and create an account, for a lousy $11. But the app’s immediacy inoculated David from the passive burden of petty debt between friends. He wouldn’t have to remember he owed me, or fear the possibility I might mentally file him away as a freeloading friend.

“It’s frustrating when someone owes you money and awkward to remind them of it,” he told me. Plus, he doesn’t have to worry about having the right amount of cash on hand.

When thought of this way, I understood. Still, the peer pressure to download the admittedly convenient apps was discomfiting, like a digital passive aggressive refrigerator note from a roommate lingering on my smartphone. Someone else was controlling my digital purse strings by asserting the means through which I should access it. You goddamn luddite, get with the times, they seemed to be saying. Fair enough. Isn’t this how most of our most ubiquitous social apps come to saturate our world — Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, Tinder, and so on? But we’re talking about savings, not selfies and swipes. Things are bound to get awkward.

Like when Caleb Garling described in a December 2013 SF Gate post about a dinner partywhere the host quietly Venmo’d his dinner party guests for the food and drink he’d served them. But Garling also came around to see the twisted, if confusing, modern logic in the interaction:

Before, such a process would have been awkward. The guests and I would have fumbled through our wallets, tried to make change, maybe cut a check, and generally tarnished the evening. Etiquette, historically a tool to maintain social order, dictated that such an exchange would be rude and weird. By asking the question, Mark would have seemed jerkish. Are things better when social pressures make Mark feel awkward for asking?

The potential for app-shaming is compounded by its social networking aspect. The millennials quoted in the Bloomberg Businessweek piece on Venmo purport to only check out their friends’ transaction notes while passing through the app: “I wouldn’t scroll through Venmo just for kicks,” one says. But the notes tend toward the quippy and emoji-filled — a perfect venue for nostalgia about last night and an inside joke (though it does let you opt out of the sharing feature so you can make your transactions private). The twenty-something staffers over at Quartz recently schooled their older coworkers on the fun of the app. My friend Robert confessed on Facebook that he’d become addicted to the app for its shared notes function: “Am I the only one who likes to look at Venmo for extended periods of time and judge the types of money being exchanged between friends? Someone get this app off my phone because it’s so entertaining. I’ll pay you. Through Venmo,” he wrote.

The app is such fertile ground for new digital etiquette questions that it knows it. The CEO of Venmo parent company Braintree, will speak on a panel at South by Southwest next month called, “Is money less taboo in a social economy?”

Swann says she’s willing to consider that it will be, that even the social sharing aspect of Venmo could become our new normal once the technology further saturates digital culture: “Look at when MySpace came out and you had parents who were flipping out thinking it was the devil and so intrusive, and now those same parents are scoffing, sharing everything about their children and grandchildren and so on on Facebook.”

If my Instagram feed is any indication, that’s already happening. Last week, my friend Melody posted a screenshot of a text conversation with her father, thanking him for Venmo’ing her some money:

“You know you’re the coolest dad ever for having that app right?”

“Cause dads need another way to get money to their kids? In the olden days, we just swiped cash from our dad’s wallets when they came home drunk and passed out.”

Amanda Palleschi is a writer of environmental policy news, features, essays and notes in the Venmo memo line that will make your mother blush. She lives in Washington, D.C. Follow her on Twitter here.

Photo: Dennis Crowley

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments